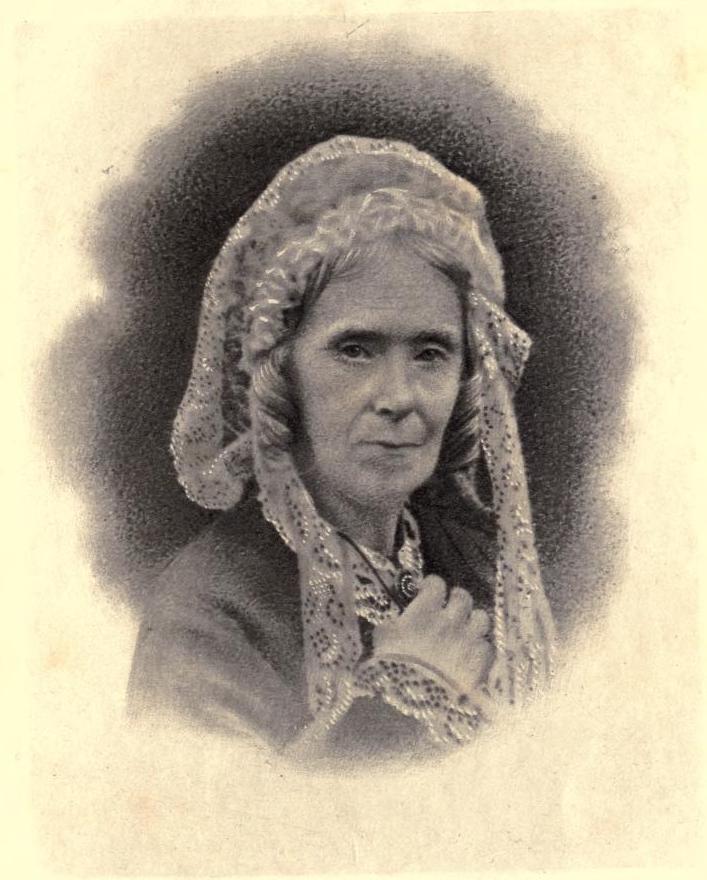

Charlotte Tucker, taken at Amritsar in about 1882.

Source: Giberne, facing p. 364.

Charlotte Tucker, who used the acronym, A.L.O.E. ("A Lady of England"), was born on 8 May 1821 in Barnet, then in Middlesex, into a large family with a long connection with India: her father would become Chairman of the East India Company, and her five brothers all went out to India, one of them, Robert, dying heroically during the uprisings of 1857. Having started writing after her father died, and having fulfilled her family duties alongside her philanthropic work, Charlotte taught herself Hindi and finally went out to India in 1875 as a missionary with the Church of England Zenana Society, visiting Indian women kept in seclusion, and working as an educationist as well. She continued writing there, always with a strong Christian message, until illness struck her down and she died in Amritsar on 2 December 1893.

The author of the following "appreciation," Mrs Marshall, was Emma Marshall (1830-99), born Emma Martin, herself a prolific and high-toned children's writer, and an opinionated critic. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

orty years ago, the mystic letters "A.L.O.E." ("A Lady of England") on the title-page of a book ensured its welcome from the children of those days. There was not then the host of gaily bound volumes pouring from the press to be piled up in tempting array in every bookseller's shop at Christmas. The children for whom "A.L.O.E." wrote were contented to read a "gift-book" more than once; and, it must be said, her stories were deservedly popular, and bore the crucial test of being read aloud to an attentive audience several times.

Many of these stories still live, and the allegorical style in which "A.L.O.E." delighted has a charm for certain youthful minds to this day. There is a pride and pleasure in thinking out the lessons hidden under the names of the stalwart giants in the Giant Killer [1868], which is one of "A.L.O.E.'s" earlier and best tales. A fight with Giant Pride, a hard battle with Giant Sloth, has an inspiriting effect on boys and girls, who are led to "look at home" and see what giants hold them in bondage.

"A.L.O.E.'s" style was almost peculiar to herself. She generally used allegory and symbol, and she was fired with the desire to arrest the attention of her young readers and "do them good." We may fear that she often missed her aim by forcing the moral, and by indulging in long and discursive "preachments," which interrupted the main current of the story, and were impatiently skipped that it might flow on again without vexatious hindrances.

In her early girlhood and womanhood "A.L.O.E." had written plays, which, we are told by her biographer, Miss Agnes Giberne, were full of wit and fun. Although her literary efforts took a widely different direction when she began to write for children, still there are flashes of humour sparkling here and there on the pages of her most didactic stories, showing that her keen sense of the ludicrous was present though it was kept very much in abeyance.

From the first publication of The Claremont Tales [or illustrations of the beatitudes, 1852] her success as a writer for children was assured. The list of her books covering the space of fifteen or twenty years is a very long one, and she had no difficulty in finding publishers ready to bring them out in an attractive form.

The Rambles of a Rat [1854] is before me, as I write, in a new edition, and is a very fair specimen of "A.L.O.E.'s" work. Weighty sayings are put into the mouth of the rats, and provoke a smile. The discussion about the ancestry of Whiskerando and Ratto ends with the trite remark — which, however, was not spoken aloud — that the great weakness of one opponent was pride of birth, and his anxiety to be thought of an ancient family; but the chief matter, in Ratto's opinion, was not whether our ancestors do honour to us, but whether by our conduct we do not disgrace them. Probably this page of the story was hastily turned here, that the history of the two little waifs and strays who took shelter in the warehouse, where the rats lived, might be followed.

Later on there is a discussion between a father and his little boy about the advantage of ragged schools, then a somewhat new departure in philanthropy. Imagine a boy of nine, in our time, exclaiming, "What a glorious thing it is to have ragged schools and reformatories, to give the poor and the ignorant, and the wicked, a chance of becoming honest and happy." Boys of Neddy's age, nowadays, would denounce him as a little prig, who ought to be well snubbed for his philanthropical ambition, when he went on to say, "How I should like to build a ragged school myself!" The voyage of the rats to Russia [see Chapter XIII onwards] is full of interest and adventure, and the glimpse of Russian life is vivid, and in "A.L.O.E.'s" best manner.

Indeed, she had a graphic pen, and her descriptions of places and things were always true to life. In Pride and his Prisoners [1860], for instance, there are stirring scenes, drawn with that dramatic power which had characterised the plays she wrote in her earlier days. The Pretender, a farce in two acts [1842], by Charlotte Maria Tucker, is published in Miss Giberne's biography. In this farce there is a curious and constantly recurring play on words, but the allegory and the symbol with which she afterwards clothed her stories are absent.

"A.L.O.E." did not write merely to amuse children; and the countless fairy tales and books of startling adventure, in their gilded covers and with their profuse illustrations, which are published every year, have thrown her stories into the shade. But they are written with verve and spirit, and in good English, which is high praise, and cannot always be given to the work of her successors in juvenile literature. In her books, as in every work she undertook throughout her life, she had the high and noble aim of doing good. Whether she might have widened the sphere of her influence by less of didactic teaching, and by allowing her natural gifts to have more play, it is not for us to inquire.

It is remarkable that this long practice in allegory and symbol fitted her for her labours in her latter years, amongst the boys and girls of the Far East. Her style was well adapted to the Oriental mind, and kindled interest and awoke enthusiasm in the hearts of the children in the Batala Schools [in the Punjab]. Here she did a great work, which she undertook at the age of fifty-four, when she offered her services to the Church Missionary Society as an unpaid missionary.

"All for love, and no reward" may surely be said to be "A.L.O.E.'s" watchword, as, with untiring energy, she laboured amongst the children in a distant part of the empire. Even there she was busy as an author. By her fertile pen she could reach thousands in that part of India who would never see her face or hear her voice. She wrote for India as she had written for England, ever keeping before her the good of her readers. The Hindu boys and girls, as well as the children of this country, have every reason to hold her name in grateful remembrance as one of the authors who have left a mark on the reign of Queen Victoria.

Bibliography

Giberne, Agnes. A Lady of England: The Life and Letters of Charlotte Maria Tucker. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1895. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 1 July 2025.

Marshall, Mrs [Emma Marshall]. "'A.L.O.E' (Mrs Tucker); Miss Ewing." "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria's Reign: A Book of Appreciations. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1897. Internet Archive, from a copy in Harvard University. Web. 1 July 2025. 293-297.

Shattock, Joanne. The Oxford Guide to British Women Writers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Created 1 July 2025