At the beginning of August 1851, Effie and John Ruskin set off for another continental tour: Venice was once again their destination. They crossed France fairly rapidly, a journey facilitated by the developing rail network. In Paris, the Rev. Daniel Moore, incumbent of Camden Chapel, Peckham Road, Camberwell, and his wife, joined the Ruskins, and would accompany them on the tour for a fortnight. The little group then took a train to Sens, where they visited the cathedral and treasure, before continuing by rail to Dijon, where they posted approximately seventy miles to Champagnole, a small town at the foot of the Jura hills heralding the approach of the real mountains beyond. It provided a fairly gentle terrain for walking, a practice area for the challenges of the High Alps.

At Champagnole, they were joined by Jane and John Pritchard who stayed with the party for nearly ten days (10-19 August) in the Jura and Alps. It was a period of challenging walks and climbs, fresh air, breathtaking views and much uncomfortable, rudimentary accommodation. From Champagnole, where Ruskin’s diary entry for Sunday, 10 August 1851, records, "Walk at Champagnole with Mr Moore and Mr and Mrs Pritchard" (Diaries, II, 469), they continued on a route well known to Ruskin – "the old road" as he affectionately called it. Higher and higher they went along twisting, narrow tracks, often with deep ravines on both sides, and eventually reached the remote mountain hamlet of Les Rousses, on the High Jura plateau, close to the Swiss border, where they stopped for the night. The next day, the party continued up more narrow winding roads before the steep descent into Geneva where they were joined by Charles Newton.

They left Geneva "with horse" at two o’clock in the afternoon of Tuesday, 12 August 1851, to get to Bonneville, "walking the last four miles with Newton and Mr Moore" (Diaries, II, 469). From Effie's long letter of Friday, 15 August 1851, to her mother, we learn much more about the journey "with horse" to which Ruskin laconically refers in his diary! Effie rode "a very nice English mare" (Lutyens1 179) from Geneva to Bonneville, a distance of approximately eighteen miles, following behind the carriage transporting Ruskin and his guests. She enjoyed seeing the lovely countryside "with the vines at their brightest green, the flowers in every garden, Hops & every kind of fruit getting ripe" (Lutyens1 180). They were taking the valley road following the course of the river Arve all the way from Geneva, via Bonneville, Cluses, Sallanches (also spelt Sallenches) and St.-Martin, to Chamonix.

After an overnight stop at Bonneville, they left early the next morning at seven o’clock: Ruskin’s amanuensis, George Hobbs, rode the horse, then Newton took over as far as Cluses. But the horse was suffering – "the saddle had skinned all its back" (Lutyens1 180) – and had to be sent back to Geneva. At the hamlet of St.-Martin, a decision was taken to climb the lofty and jagged mountain range of the Reposoir (Diaries, II, 469). To reach these mountains, they had to cross the single-arched bridge over the Arve, "clearing some sixty feet of strongly-rushing water with a leap of lovely elliptic curve" (35.447), adjoining the little village of Sallanches. Sallanches, that Ruskin had first visited in 1833, had been totally destroyed by fire in 1840, thus exacerbating the physical distress that Ruskin observed almost everywhere in Savoy. The town was gradually rebuilt, and by the late nineteenth century had risen from the ashes. Cluses likewise suffered a similar catastrophe in 1844.

They stayed overnight at St-Martin, at the Hôtel du Mont-Blanc, a place charged with emotion for Ruskin, "of all my inn homes, the most eventful, pathetic, and sacred" (35.433). An entire chapter in Praeterita is entitled "Hotel du Mont-Blanc" (35.433-456). By 1882, the little hotel was deserted, and for sale, and Ruskin was considering purchasing it. The party continued along the Arve valley to Chamonix, among the snow-capped peaks, in the shadow of Mont Blanc, arriving in time for lunch, for the "Table D’Hôte at two", at Ruskin’s usual hotel, the Hôtel de l’Union. (Lutyens1 180)

Glacier des Bois. John Ruskin. 1843. 2.224.

There was no respite! More mountain walking followed. No sooner had they had lunch than Ruskin exhorted the more willing members of his party to tackle the mountain range of the Montanvert (variously spelt as Montenvers). After a short, leisurely stroll following the Arve northwards, they soon turned in an easterly direction, at the point where the river Arveyron joins the Arve, through woods to the village of Les Bois from where a zigzag path rises rapidly through thick forests. Ruskin wanted to show his friends the Source of the Arveyron beneath an ice-cavern in the mountains, at the extremity of the huge Mer de Glace and more precisely at the tip of the much smaller Glacier des Bois. The effects of erosion and glacial recession were already visible. Ruskin had sketched the Glacier des Bois on a previous visit some ten years before and captured the giratory effect of sunlight on the ice contained within the hollow cavern (facing 2.224). By 1863, he was extremely worried and wrote to his father: "The glaciers below have sunk and retired to a point at which I never saw them till this year; if they continue to retire thus, another summer or two will melt the lower extremity of the Glacier des Bois quite off the rocks" (36.454). By 1891, the Glacier des Bois had retreated so far that Murray’s Handbook for the Alps of Savoy and Piedmont stated that it was "scarcely worth a visit". How accurate Ruskin’s observation and premonition had been, for by the twentieth century, the Glacier des Bois had disappeared completely, and was not even indicated on the official map of Chamonix and the Massif du Mont Blanc published by the Institut Géographique National in 1990.

Effie did not share the expedition to the Glacier des Bois. Instead, she left Chamonix by mule, accompanied by Judith Couttet, the daughter of Ruskin’s trusted guide, Joseph Couttet, and went straight to the refuge, a tiny, very basic hut at the top of the Montanvert where the party was spending the night. Effie arrived rested and refreshed after her two-and-a-half-hour ride, in contrast to the state of exhaustion of her husband’s friends. In a letter to her mother, she described the scene: "I found John had nearly killed with fatigue his friends who were drinking Brandy & water and Mr Newton calling him an enragé. We slept here all night and were only disturbed by a storm of thunder & lightning very fine indeed" (Lutyens1 181).

There were other walks and climbs to the icy peaks and needles of the Aiguilles des Charmoz, the Glacier des Bossons and the Glacier des Pèlerins. What is surprising is not only the degree of mountain walking, some quite hazardous, packed into a short stay, but the fact that Ruskin and his party did not have an official guide. Since Ruskin's favourite guide, Joseph Couttet, was not available, Ruskin may have decided to dispense with a guide because he felt he knew the area extremely well, having already stayed in Chamonix in 1833, 1835, 1842, 1844, 1846 and 1849.

Jane (and John) Pritchard walked up the Montanvert and to the Mer de Glace on 15 August 1851 (Lutyens1 181), but in reality few women ventured high into the mountains, one of the obstacles being of a very practical nature, their cumbersome long skirts. However, on 2 September 1860, on a visit to mark the incorporation of Savoy into France, Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoléon III, is pictured riding sidesaddle on a mule on her way up to the Mer de Glace: she is wearing a long flowing dress and a hat with a veil more suited to Paris (Ballu 73). John James Ruskin, writing to Elizabeth Fall (sister of Richard) on 16 September 1856, observed with some distaste the apparel of ladies wearing "a man's hat queerly turned up at the sides and a few disfigurations of this kind at Chamouni upon mules" (Letter of JJR to Elizabeth Fall, written from the Hotel Liverpool, 11 rue Castiglione, Paris, ref. MsL 3/3/3, Lancaster).

Chamonix in 1851 was at a turning point, changing from a remote, tranquil village to a "tourist rendezvous" (35.436). The delights of Chamonix and its glaciers were being vigorously promoted. The following advertisement in Galignani’s Messenger, the European English-language newspaper read mainly by British tourists abroad, appeared on 21 August 1851, under the heading GLACIERS OF CHAMOUNI:

A casino is open for the season at this favourite summer resort. Music, refreshments, and reading-rooms. N.B. – Every kind of amusements, as at Baden-Baden, Hombourg, etc. Branch establishment at the Spa of Evian, on the Lake of Geneva (6.456n1).

Ruskin had left behind the Great Exhibition in London that he decried, only to find himself in the centre of another kind of commercialisation underway in Chamonix, brought about by one of his compatriots. The exploits of Albert Smith (1816-1860), a doctor turned climber and showman, coincided exactly with the summer stay of Ruskin and his party. "There has been a cockney ascent of Mont Blanc", Ruskin announced to his father on 16 August 1851, "of which I believe you are soon to hear in London" (36.117). Smith orchestrated his ascent of the highest peak in Europe to give him maximum publicity. He was not climbing to study or appreciate the mountain, but to use it as a stunt, an act of blasphemy in Ruskin's eyes. From his base at the Hôtel de Londres, he made sure that news of his elaborate preparations and date of his ascent (12 August) reached far and wide. His was the largest climbing party ever to leave Chamonix. It consisted of sixteen guides, led by Jean Tairraz, followed by eighteen porters carrying the most sophisticated of provisions – sixty bottles of vin ordinaire, thirty-one bottles of vintage clarets and burgundy, cognac, champagne, chocolate, dried fruit, four legs and four shoulders of mutton, six pieces of veal, one piece of beef, eleven large and thirty-five small fowls, bread, salt and candles. Smith was accompanied by three Oxford undergraduates whom he had met, rather casually, at his hotel: they were Francis Philips, George Charles Floyd and William Edward Sackville West (Fitzsimons 111). All were "in light boating attire" (115). The ascent was dangerous but successful. Smith and his men eventually reached the summit at nine o'clock the following morning. They had bivouacked for a few hours at the Grands Mulets, opened some of their food and wine, lit a fire and rested until midnight when they continued their climb by means of the reflected moonlight. The ascent provided Smith with material to entertain and hold audiences spellbound at his series of dioramas at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly: Henry James was among those who found them fascinating. Smith also made a great deal of money from his shows. Sir Robert Peel, an amateur climber who had arrived in Chamonix just after Smith's party set off, was fascinated by the ascent, and all night long, in moonlight, watched their every move through a telescope, willing them to succeed and merrily drinking their health (121).

A trend – unstoppable – had been set and the character of Chamonix had changed forever. More and more visitors were arriving. The peaks around were becoming popular attractions for tourists: at one time, Effie counted forty mules on the Montanvert. Business was booming for hoteliers such as the landlord of the Hôtel de l'Union. In 1903, following in the steps of Ruskin, Marcel Proust and his friends Louisa de Mornand and Louis d'Albufera, went on mules to the Montanvert and the Mer de Glace.

By 1856, Albert Smith and Emma Forman were enjoying their exploits and the surrounding publicity. In a perverse way, and in spite of their criticisms, the Ruskin family encouraged the crowds by their participation in the events. John James Ruskin's lively account is most revealing:

Albert Smith has sent half the travellers abroad straight to Chamouni & a few up Mont Blanc. We saw Miss Foreman go off for the ascent & return none the worse being the fourth lady only who has yet ascended the Mountain. She gave my son a full account of her adventure – of visitors to Chamouni we counted coming up one evening 17 carriages full & the Landlord of Union said he had dispatched same morning 23 carriages. [Letter of JJR to Elizabeth Fall, 16 September 1856, ref. MsL 3/3/3, Lancaster. The "e" in Forman has been struck through, possibly a correction made by John James on realising his mistake.]

Ruskin was not immune to the thrills, and wrote in his diary of 1 August 1856: "Yesterday to Les Ouches [...] up to Aiguille Blaitière, & then to meet Emma Forman coming down from Mont Blanc at the Pelerin wood" (Ms 11, fol. 26, Lancaster). In Modern Painters IV (1856), Ruskin wrote: "The valley of Chamouni, another spot also unique in its way, is rapidly being turned into a kind of Cremorne Gardens" (36.456).

In this stimulating company (in 1851) with compatible companions of his own choice, away from his overbearing parents who fretted and were frightened if their son was even five minutes late for tea, striding among the rocks in the bracing Alpine air, picnicking in the woods, Ruskin was enjoying some of his happiest moments. He felt "refreshed" (36.117), and was harnessing his strength for the challenge that lay ahead – the huge volume of work he intended to do in Venice during the long winter of 1851-52.

Venice

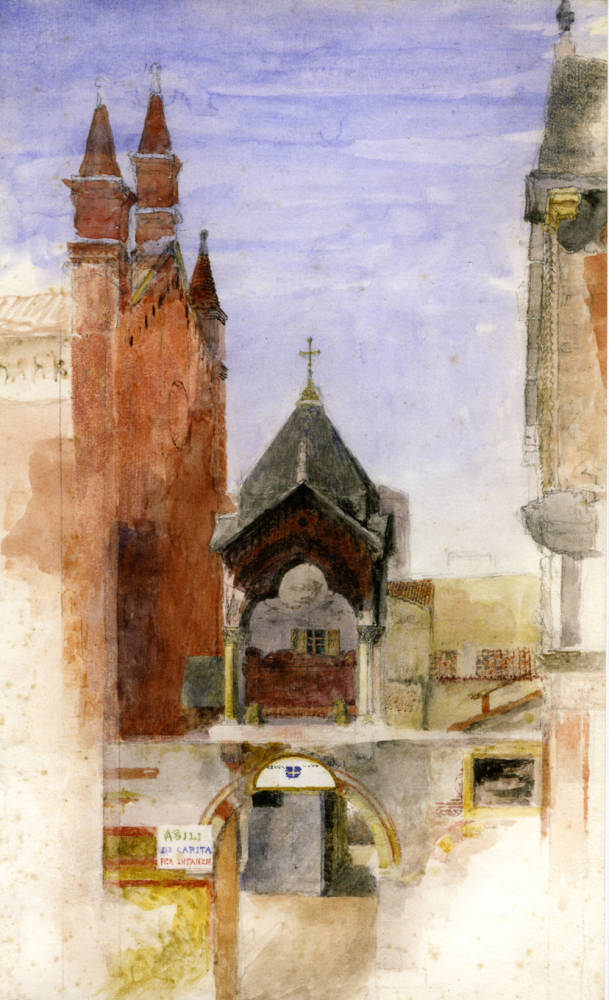

Ruskin watercolours of Geneva and Verona. Left: Old Houses at Geneva. 1841. Middle: The Tomb of Can Grande della Scalla, Verona. 1845. Right: Castelbarco Tomb, Verona. 1869 or earlier. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

After an itinerary including Geneva, Aosta, Ivrea, Vercelli, Milna, Brescia and Verona, Effie and John Ruskin arrived in Venice in early September 1851. They set up home at the Casa Wetzlar instead of at their usual hotel, the Danieli. The Wetzlar was in a convenient location in the sestiere of San Marco, close to the church of Santa Maria Zobenigo and only a few steps from La Fenice opera house. Ruskin enjoyed a short period of comparative calm thanks to the immense practical support afforded by Brown (who helped to find the new lodgings) and Cheney. By mid-September, Ruskin wrote of his happiness to his father:

I am now settled more quietly than I have ever been since I was at college – and it certainly will be nobody's fault but my own if I do not write well – besides that I have St Mark's Library open to me, and Mr. Cheney's: who has just at this moment sent his servant through a tremendous thundershower with two books which help me in something I was looking for. [Bradley 15]

Ruskin made much use of Cheney's library as the reading room in Venice had closed down (Bradley 66).

Effie was overjoyed to be mistress of the house, to invite and be invited. Among the first guests, invited for tea on 8 September, were Edward Cheney and one of his nephews, Henry Hart Milman, Dean of St Paul's Cathedral, London, and his wife (Lutyens1 189). This was a potentially explosive mixture – and an occasion for which Rawdon Brown had sent his apologies – for Ruskin did not see eye to eye on many issues with Milman and Cheney. Invitations to tea were exchanged, although Ruskin was embarrassed to receive Cheney and Brown in the relative poverty of the Casa Wetzlar: "their own houses are much more luxurious that ours", he informed his father, "so it is a small compliment to ask either of them to come" (Bradley 35).

But the promised calm did not last, and Ruskin began, ungraciously and ungratefully, to be critical of Brown and Cheney. "They are both as good-natured as can be," he explained to his father, "but of a different species from me – men of the world, caring for very little about anything but Men" (Bradley 35). This was an unjust assessment of two well-educated men who provided Ruskin with invaluable practical assistance during his Venetian sojourns. He made little attempt to enter their spiritual and aesthetic worlds. By distancing himself from Cheney, Ruskin also missed a unique opportunity to discover inside information about Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) whom he greatly admired. For Cheney had been Scott's cicerone in Italy during the last years of his life, and would have had many stories to tell, even being able to contribute to the biography that Ruskin was contemplating writing.

As work continued unabated on the second and third volumes of The Stones of Venice, Effie spent more and more time without her husband. She longed to socialise more, to go to the theatre to see the great tragic actress Mademoiselle Rachel (1821-1858) playing the central roles in Racine's Phèdre and Corneille's Horace at the Teatro San Benedetto. Cheney and Brown thought Rachel "very grand", and went to four of her performances (Lutyens1 192). Although Ruskin was an avid theatre-goer, he declined to go to the theatre on this occasion, perhaps on account of his heavy work schedule. Cheney and Brown wanted to take Effie with them but she hesitated and eventually refused on the spurious grounds of Rachel's immoral reputation. It was a missed opportunity, for Rachel, although only thirty years of age, was reaching the end of her life, and like Dumas' heroine of La Dame aux camélias (1848) and Verdi's La Traviata (1853), would die of consumption in her prime. Effie's coy refusal may have been motivated by her fear of being reprimanded, even ostracised, by her severe, critical parents-in-law at Denmark Hill.

Cheney was a meticulous host and organised his receptions and dinners to perfection. He entertained frequently, so frequently that Ruskin was obliged, on occasions, to refuse invitations. He accepted out of politeness, as Effie explained to her parents in a letter of 17 November 1851: "The other day [we] dined at Mr Cheney's where John went as he did not wish to offend Mr Cheney by refusing so often" (Lutyens1 214). Guests at the "elegant little dinner" included Cheney's companion Rawdon Brown and an assortment of aristocrats and émigrés.

Ruskin's eccentricities and egoistical, opinionated behaviour did not go unnoticed by Cheney and Brown who found his company awkward. This led to a temporary cooling of relationships but one that Effie's great charm, sociability, and tact managed to overcome. The relationship was repaired, and on Christmas Day 1851 the young Ruskins were invited, along with Edward Cheney, to dinner by the English Consul-General, Clinton Dawkins and his wife. They resided in a spacious and "most beautiful apartment" in the Palazzo Barbaro, with a ballroom with "frescoed and stuccoed walls and [Tiepolo] ceiling" (Lutyens1 237) capable of accommodating over two hundred dancers. In spite of the presence of potentially interesting guests, Ruskin did not enter into the spirit of the occasion, and conducted himself in an embarrassingly anti-social manner, as Effie reported to her parents: "I left at half past nine as John looked bored as he sat in a corner reading by himself, but he never talks to any body and he says his great object is to talk as little and go through a dinner with the smallest possible trouble to himself – and I suppose it is best just to let him do so although I think it is a great pity that he does not exert himself to speak more as he speaks so well" (Lutyens1 238). At Marshall Radetzky's prestigious January Ball (1852), Ruskin found a "quiet seat – and a book of natural history" (259n1). He was, Effie recognised, "very peculiar" (Lutyens1 264), and increasingly so!

As the year drew to a close, Ruskin's attention was focussed again on Turner on learning of his death in late December. The possibility of purchasing more Turners might arise if they were released onto the art market and Ruskin discussed the matter with his father. He recalled a Turner drawing from Cheney's collection that he had bought "on account of the pig in it" (Bradley 195). It was the original of one in the Liber Studiorum: Bradley suggests it was a first study of Turner's Farmyard and Cock (Bradley 195n4). Ruskin had a strange fascination with pigs – in art and as farm animals. Presents of home-produced pork were often sent by Ruskin's mother: Turner was a recipient of such a gift in 1845.

Ruskin did not share Edward Cheney's passion for classical art. So in 1851, when Cheney became an unofficial consultant to the trustees of the National Gallery, London, advising about the purchase of Italian paintings, clashes with Ruskin were inevitable. On one occasion, a dispute arose about the colours of some mosaics. Ruskin wrote to his father: "I got into a little dispute with Mr. Cheney about some mosaics one day – and was quite nervous the whole day after – merely a question of whether the colours were faded or not" (Bradley 171).

Like Henry James, Ruskin was horrified to find so many paintings in Venice in danger, and campaigned to persuade the National Gallery to enrich their collections with great Venetian paintings, thereby also rescuing them from neglect. In March 1852, he approached one of the trustees, Lord Lansdowne, about the perilous state of many of the precious works of art in Venice: "It is a piteous thing to see the marks and channels made down them by the currents of rain, like those of a portmanteau after a wet journey of twelve hours; and to see the rents, when the bombshells came through them, still unstopped" (12.lx).

Two Tintorettos were of particular importance to Ruskin: the Crucifixion that he considered to be "among the finest in Europe" (11.366), hanging in the church of San Cassiano, and the immense Marriage in Cana in the church of Santa Maria della Salute. Ruskin knew the commercial, as well as the aesthetic value of works of art. He informed the painter Sir Charles Locke Eastlake (1793-1865), then one of the prominent trustees of the National Gallery (its Director in 1855), that he could purchase, for the National Gallery, the Crucifixion for £7000, and the Marriage in Cana for £5000. That was a considerable sum of money.

Ruskin sensed potential difficulties with powerful, influential Cheney. He knew that the matter was extremely sensitive, and had discussed it with him at great length and in such a way, so he thought, as to avoid making him jealous, for a "word that piqued him might have spoiled all" (Bradley 281-82). For many years, Cheney had enjoyed a certain hegemony in matters of art, and probably felt susceptible to being usurped by a now famous and controversial art critic sixteen years younger. However, Ruskin believed he had convinced Cheney to agree to the purchase. The two men were extremely different and viewed each other with a degree of disdain, suspicion and dislike, yet distant respect. Cheney revealed his opinion about Ruskin and Effie in a letter to his friend Lord Holland:

Mrs Ruskin is a very pretty woman and is a good deal neglected by her husband, not for other women but for what he calls literature. I am willing to suppose he has more talent than I give him credit for – indeed he could not well have less – but I cannot see that he has either talent or knowledge and I am surprised that he should have succeeded in forming the sort of reputation that he has acquired. He has so little taste that I am surprised he admired Holland House. [Quoted Lutyens1 225]

Effie perceptively recognised that Cheney's (and Rawdon Brown's) satirical manner and anger towards her husband was a façade to conceal their acknowledgment that "he knew much better about art here than themselves" (Lutyens1 224). Ruskin, on the other hand, felt that Cheney was a man of great talent and "excellent judgment" (24.187) in matters of Venetian art but who did not apply himself. Eastlake contacted other Trustees who in turn consulted Cheney, the final arbiter who, Ruskin believed, "put a spoke in the wheel for pure spite" (35.504). Ruskin's powers of persuasion had not worked. Effie too had tried hard and had taken several initiatives to try and ensure a successful outcome. She enlisted the help of Lord Lansdowne, and discussed the matter with Cheney and Rawdon Brown (Lutyens1 304). According to Effie, Cheney wrote "a capital letter" of support to the Treasury in London: but this may not have been entirely true for Cheney and Rawdon Brown were doing their best to discourage and dissuade Ruskin from the project because they believed that it would be "quite impossible to get Church property" (Lutyens1 316). One of the official reasons for refusing to proceed with the purchase was that "Mr. Cheney [did] not entirely concur with [Mr. Ruskin] in his valuation of the works" (12.lxi; for a detailed analysis of the affair, see Gamble.) However, a major point overlooked by Ruskin was that the paintings in question were not for sale!

Innumerable invitations to balls, parties, soirées continued, and Effie became more and more accustomed to this kind of life. It was a shock for her to realise that the end of this enjoyable Venetian existence was in sight, and that she would soon have to return to England and face the realities of being in close proximity to the old Ruskins. She learnt that John James Ruskin, without consulting his son and daughter-in-law, had taken a seven-year-lease on No. 30 Herne Hill, immediately next to No. 28, the house still owned by Mr Ruskin and let on a lease. Effie craved Belgravia, not a secluded spot in a quiet rural setting. Her dislike of her parents-in-law had increased during the two long Venetian stays when confidential letters, sometimes critical of her lifestyle and expenditure, were passed around between the Grays and the Ruskins. Effie revealed her feelings in a letter of 17 April to her parents:

I have found it equally impossible to be fond of Mrs R[uskin] or to trust Mr R[uskin]. I always get on with them very well but it is at a great loss of temper and comfort, for the subjection I am obliged to keep myself in while with them renders me perfectly spiritless for any thing else. One of the things that distress me perhaps most is hearing them all railing against people behind their backs and then letting themselves be toadied and flattered by the Artistic canaille by whom they are surrounded.

She added: "I am quite of Mr Cheney's opinion that of all canaille they are the lowest with very few exceptions" (Lutyens1 297).

In late April, Cheney too was preparing to leave Venice. "He is", Effie reported to her parents, "going to give up his beautiful rooms here and return to England, selling most of his furniture and taking all his pictures and articles of vertu with him. His departure will be a great loss to Mr Brown and Mr Dawkins, who are great enemies but curiously enough are both great friends of Mr Cheney's" (Lutyens1 301).

On 15 May 1852, Effie and John Ruskin took new lodgings on the Piazza San Marco. Effie, seemingly without her husband, went to Cheney's palazzo for a farewell dinner: Rawdon Brown was also invited. The mansion looked "very dismantled but all concerning the dinner was perfect", Effie wrote to her parents (Lutyens1 313). But it was a sad occasion, for close friends were about to disperse. Rawdon Brown was unusually quiet, apprehensive about being alone in Venice. "He is really very fond of us I think", wrote Effie, "and the idea of us all going and leaving him alone, for he has literally no one else, made him I thought very dull for he generally talks so much" (Lutyens1 313). Cheney was "much out of humour at having to go back to England" (Lutyens1 318). His sister Harriet, wife of Robert Pigot, had died on 25 March 1852, "after a long and wasting illness", aged forty-six years, according the inscription on her memorial stone carved by John Gibson in Badger Church. Perhaps Cheney felt the need to be closer to his existing siblings and to take a greater role in the management of Badger Hall.

The Ruskins' departure from Venice was delayed by an "unfortunate affair" (Lutyens1 320) – the theft of Effie's best jewels, including a diamond bird and a heart, her blue enamel ear-rings, a chain of pearls, and several items such as diamond studs belonging to her husband. Suspicion fell on "a gentleman, an Englishman, and an Officer serving in the Emperor's own Regiment" (Lutyens1 323), a friend whom Effie trusted implicitly – Mr Foster. Foster was a confidant of Radetzky and of Count Thun, Radetzky's aide-de-camp. Thun seemed to think that Ruskin had accused his friend of the theft. Unsubtantiated rumours easily inflamed an already tense political situation: honour was at stake and Ruskin was challenged to a duel. Effie and her husband were the subject of suspicion and much unpleasant gossip. Once again, Cheney and Brown came to their rescue: they were "exceedingly kind" (Lutyens1 326), helping them to cope with the Venetian authorities and police methods, and advising them to leave Venice as quickly as possible. Ruskin wrote to his father: "Mr Brown and Mr Cheney, both men of the world, are my advisors in anything requiring advice" (Bradley 304). Cheney wrote a letter of explanation on behalf of the Ruskins, to Dawkings, the English Consul, requesting that all possible help be given in the circumstances (Lutyens1 331-32). Cheney and Brown thought that the Ruskins should have applied to Radetzky for an escort to conduct them out of the Territory (Lutyens1 339).

Ruskin took a detached, self-righteous view of events, and considered that Effie had been taught a lesson about being careless with her jewels. The affair, Ruskin informed his father, had brought out the very best in Cheney: "One thing I am very glad of among the other good consequences of a misfortune, it has brought out Mr Cheney's character; I believed him to be a man like Mr Beckford. I have found him active – kind – and right-minded, in the highest degree, and he has been my chief advisor and support in this affair in which not only single words – but tones of words, were of great importance" (Bradley 308). Although doubtless preoccupied with his imminent departure, Cheney had gone to great trouble to help the Ruskins out of a potentially dangerous situation – imprisonment and a duel – and one wonders to what extent he was appropriately rewarded. It was Effie alone who appreciated his totally indispensable role: "Mr Cheney has also left now and gone home by Vienna. Nothing could exceed his good nature in this business of ours and the respect I have for his great probity and knowledge of the world and what ought to be said and done. Although John and myself wished to do every thing that was right, also the Consul & Mr Brown, Mr Cheney advised us all, and without him we should I think have committed some bêtise or other" (Lutyens1 334).

As the couple journeyed back to England, Effie's thoughts were of Venice, Cheney, and Brown. From Airolo, north of Locarno, she wrote a sensitive and kindly letter to Rawdon Brown, alone in the Serenissima:

I am afraid you will now be feeling Mr Cheney's absence very much but you are sure to see him very soon again. He said to me that he would return to see you and I don't think England will hold him very long. He is so good and perfect in every way that I think you are favoured in having had such a friend so many years. I never ceased admiring both he and you in this late affair of ours and without you both I am sure I do not know what we should have done. We very likely might have committed some bêtise which would have kept us in Venice till now and weeks longer. [Lutyens1 335]

Cheney stayed on for a while in Vienna from where he reassured Effie that news of the theft had not reached that city (Lutyens1 341). However, British newspapers reported the affair and eventually Ruskin was obliged to write a letter to The Times in his defence.

From Venice, Ruskin had maintained regular contact with Osborne Gordon, who, on 5 February 1852, had been nominated as a Moderator under the New Examination Statute for Greek and Latin (Times 6 February 1852). Ruskin often shared letters with his father as was his custom. It was an irritating habit that denied correspondents any confidentiality or privacy. "I will enclose a line for Gordon tomorrow", he informed his father on 8 May 1852 (Bradley 273). But it was not a sealed letter for Ruskin was under an obligation to show the contents to his father. Hence he wrote the next day: "Please enclose the enclosed to Gordon. There is not much in it to interest you, but you would be disappointed perhaps if you had it not to look over" (Bradley 276). In a letter of 7 June 1852 to his father, he discussed Gordon's religious tendencies: "The letters of Gordon and Colquhoun are interesting – but Gordon is quite a Gladstone man himself, now. I mean very high church, and not knowing exactly what he would be at" (Bradley 299).

The death of the eighty-three-year-old Duke of Wellington on 14 September 1852 was followed by a State funeral on 18 November. Effie was given two coveted tickets, by Dean Milman, to attend the Iron Duke’s elaborate funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral, London (Lutyens1 189n). Since Ruskin refused to go to the funeral, a "ridiculous and tiresome pageant" (Quoted Hunt 223), Effie asked her father to accompany her. Ruskin had mixed feelings about being replaced by Mr Gray and expressed them to him: "I am partly happy – partly sorry that Effie has persuaded you to come up to the Duke's funeral" (Lutyens2 26). Ruskin had had a severe disagreement with Milman the previous year when in Venice, as he explained to his father: "I showed the Dean of St Paul’s over the Duomo of Murano yesterday," he informed his father, "abusing St Paul’s all the time, and making him observe the great superiority of the old church and the abomination of its Renaissance additions, and the Dean was much disgusted" (10.xxxiii).

The Duke of Wellington had been Chancellor of Oxford University since 1834, and was also a member of Christ Church. His death gave Gordon an opportunity to be on centre stage, at least in Oxford, where he gave the Censor’s speech, in Latin, on the loss of the Duke. It was an impressive tour de force, "cast in an heroic mould; […] classical in form and sentiment; and hardly [bore] translation from the Latin, in which Mr Gordon thought as he wrote" (Marshall 32). In churches and cathedrals throughout the land, there were polished orations commemorating the Duke’s life and heroic deeds.

Last modified 10 March 2020