Osborne Gordon. Courtesy of Mr. Roger Pope. Click on image to enlarge it.

On 30 May 1865, a faculty was applied for "whereas it hath been made appear unto Us that it is desirable that the Parish Church of Easthampstead aforesaid should be taken down and rebuilt as far as may be found practicable" (Collins 25). This decision was reported in the Illustrated London News of 15 July: "The church of Easthampstead, Berks, being in a very dilapidated conditon, the Rev. Osborne Gordon, the Rector, the Marquis of Downshire, Sir W. G. Hayter, and other proprietors have decided upon the rebuilding and enlarging the body of the church and erecting a chancel" (38). This was a drastic measure and one that Ruskin would have surely opposed. However, Ruskin’s late father, John James, had already made a financial contribution to the rebuilding of the church (as he had to both the building in 1843 of St Paul’s Church, Herne Hill, and to its rebuilding, after a fire, in 1858), so any opposition by his son would have been deemed inappropriate. One can speculate on the discussions that took place, from the time of Gordon’s appointment, between John James Ruskin, his son, and Gordon about the problems. Challenges appealed to Gordon and soon he succeeded in charming and winning over local landowners and church patrons the Marquis and Marchioness of Downshire who contributed a substantial, but insufficient sum of money towards the estimated cost of the rebuilding. Fundraising continued over several years: concerts were given at Easthampstead Park, the home of the Downshire family, such as one on Tuesday, 30 October 1866 to "liquidate the debt incurred by the rebuilding of the parish church" (The Illustrated London News 3 Nov. 1866 427).

By April 1865, architect John West Hugall (fl. 1849-1878) had produced six drawings entitled The Church of St Michael, Easthampstead, Berks (dated April 1865). Another four, entitled The Church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead, Berks. , are undated. A drawing entitled A Proposal for the Rebuilding of the Tower is dated September 1873. All the drawings are tinted with watercolour and some have comments by Hugall. (I am grateful to the Rev. Guy Cole for drawing my attention to these sketches, held in the RIBA Collection of Drawings, ref. Easthampstead, PB179/25 (1-11).)

Hugall had already established a reputation in Berkshire where he had been responsible for St James's Church, Bourton (more recently in Oxfordshire), completed according to Pevsner in 1860 (92). But perhaps of greater relevance was the fact that Hugall had been the architect responsible for the design of Gordon’s rectory at Easthampstead, described by the Reading Mercury of 4 May 1867 as "a very happy result" (2).

The Illustrated London News of Saturday, 7 October 1865 reported that the first stone of the new Easthampstead church was laid by Lady Hayter, wife of the Right Hon. Sir W. G. Hayter, the Rector’s churchwarden, on 29 September 1865 (see also Berkshire Chronicle, 7 October 1865). The foundation stone, inscribed A.S. 1865, can be found at ground level on the outside of the east wall.

Left: Natural History Museum. University of Oxford. Architects: Woodward and Deane. 1858. Right: The Museum’s Iron and glass roof. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Gordon had been at Oxford during the controversial building of the Oxford Museum, constructed in the late 1850s and designed by Dublin architect Benjamin Woodward in the Gothic Revival style. He was well aware of the debate and heated arguments surrounding the choice of style and materials (not forgetting the virulent theological debates). The initiative for a science building and museum of natural history came from Henry Acland, and the architectural initiative from Ruskin. But Ruskin was not in charge of the project and remained ambivalent and never satisfied with it: that was his nature. He was critical of some of O’Shea’s carving as "not yet perfect Gothic sculpture": although a wrought-iron spandrel on the roof depicting horse-chestnut leaves produced "a more agreeable effect than convolutions of the iron could have given", he did "not call it an absolutely good design" (The Oxford Museum 84, 88-89). Nevertheless, whatever reservations Ruskin harboured, he contributed an undisclosed amount for decoration for "Completing the Doorway and the sculptures of the West Front" – along with twenty-five named individuals and some unnamed architects (107). Ruskin also donated £300 "towards carving the windows of the Front" (106). Ruskin’s father sponsored the statue of Hippocrates, the "father of medicine", sculpted by Alexander Munro, at a cost of between £70-£100 (103): John James’s name appears next to that of Queen Victoria who funded statues of the scientists Bacon, Galileo, Newton, Leibnitz and Oersted. Gordon is listed as one of the "Donors of Shafts costing £5 and upwards" (104).

To what extent was Gordon influenced by the Gothic Revival, by the furore over the University Museum and of course by Ruskin in the choice of his architect for his church? And to what extent did his wealthy donor influence decisions?

Vestiges of the previous church at Easthampstead were retained, such as a small slab mounted within the red brick on the exterior west wall inscribed "Henry Boyer, 1664", and the pulpit base dating from 1631.

Detail of the oak lid of the font at the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene, Easthampstead. July 2014. Photograph by the author.

The octagonal font, also from the earlier church, is covered by an oak lid elaborately and finely carved with leaves, flowers and various symbols: in one of the segments two doves facing each other (a symbol of concord) are partly separated and framed by a Greek cross and foliage.

30 April 1867: Re-consecration of the church

The Church of St Mary Magdalene and St Michael. Photograph by the author.

The new church was dedicated to St Mary Magdalene and St Michael, an order that was reversed in the 1890s. The re-consecration by Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, took place on 30 April 1867, in a service commencing at 11.30 a.m. No Order of Service is known to survive, but we know a little more about the event thanks to an anonymous reporter for The Times, whose article was published on 3 May 1867:

Easthampstead, Berks. – The new church in this parish, which has taken the place of a very ancient and ruinous fabric, was consecrated by the Lord Bishop of Oxford on Tuesday last. The church consists of a nave, with its south porch and baptistry; a north aisle and Downshire south transept, with the chancel and a south aisle set apart as a vestry and organ chamber. The entire length is 112 ft, and the nave is 27 ft wide. The style of architecture adopted by the architect, Mr. Hugall, is an early type, embracing Byzantine and first pointed details; the various mouldings are bold and massive, as, indeed, are all the members, and there is a substantiality about the whole building which arrests the attention and satisfies the eye. The windows are large and filled with rough plate-glass, on which are painted, in the usual manner of stained glass, various emblematical plants, such as the vine, passion flower, fig tree, wheat etc. All the wood-work is of red deal, varnished. There is considerable quantity of Devon marble introduced, and the carving of the capitals, corbels, etc, is rich in design and exquisite in workmanship. The benches are all open, the chancel fittings are of oak, and a sedile for the Bishop is formed by the elongation of the north window-sill, and an oak desk is placed in front. By the side of this seat a credence is fixed, consisting of a marble shaft, with stone base, carved cap, and canopied cover, surmounted by a cross. A double sedilia occupies the south window; the altar of oak, which was vested with a splendid velvet frontal, designed by the architect, worked by Miss Monck, and offered by the Rev. J. Bennett, has above it, in the central panel of the reredos, a large cross of red Devon marble, which will eventually be surrounded by carved symbols of the Evangelists and a device in rich mosaic and malachite. The pulpit, which is on a stone base, is composed of portions of that fixed in the church in 1631, and has a beautiful velvet hanging worked by a cousin of the Rev. Osborne Gordon, the rector, through whose instrumentality this noble work has been carried out. The collection at the offertory on the occasion of the consecration amounted to 100 L [pounds], which leaves a deficit of about 250 L [pounds] to be provided for.

The Berkshire Chronicle of Saturday, 4 May 1867, page 6, also reported on the re-consecration.

Osborne Gordon embellishes his church

The report in The Times pointed out the subdued and fairly plain nature of the glass in the church windows, certainly not the strong colours of the medieval stained glass of Chartres cathedral: "The windows are large and filled with rough plate-glass, on which are painted, in the usual manner of stained glass, various emblematical plants, such as the vine, passion flower, fig tree, wheat etc." In a personal note on one of his drawings, Hugall has written: "The windows in the chancel and baptistery are glazed in plain glass in the hope that stained glass may be inserted" (Cole). Another annotation by Hugall continues: "The rest are filling with rough plate in horizontal sheets on which are permanently drawn in outline foliage of the vine, fig, passion flower, wheat, shamrock in the Downshire Aisle" (Cole)

The Rev. Guy Cole points out that a fragment of Hugall’s "outline foliage", on the opaque white glass, rough in structure, with the black outline of a plant with berries, survived, up to the early twenty-first century, in a little window in the Sacristy. The repeated vandalism of this historic window in 2006 was such that it was smashed beyond repair. David Price, the stained-glass artist, managed to create a window based on the original fragments: this was dedicated at Candlemas in 2007 to the memory of Pam Reader whose family bore the cost. Cole emphasises that this "window is now the only reminder of what the windows looked like before Sir Edward Burne-Jones" (Cole).

Gordon enhanced and embellished his church with quality ornament, sculpture, furniture and brightly coloured stained-glass windows. Gradually, over several years, most of the rough plate-glass was removed and carted away or perhaps buried in the ground near the church.

Cynthia Gamble and Ian Gordon at the grave of Osborne Gordon, 23 July 2017. Photograph by kind permission of Matthew Cheung Salisbury.

The 150th anniversary of the re-consecration and rebuilding of the church was celebrated by a series of events in 2017, including a special afternoon dedicated to Osborne Gordon and Ruskin on 23 July. The homage consisted of a lecture entitled "Osborne Gordon: Ruskin's Oxford Tutor" by Cynthia Gamble, delivered in the church, against the backcloth of the magnificent, sunlit East Window. Ian Gordon, a descendant of Osborne Gordon, was warmly welcomed and gave a personal insight into his family. After the talk, a delicious afternoon tea was served in the community room adjoining, where friends could mingle and enjoy conversation. A special delight was a pilgrimage to the grave of Osborne Gordon, in the churchyard, where a wreath of white roses was laid and blessed by the Rev. Guy Cole in a short ceremony of prayers. The afternoon concluded with Choral Evensong in memory of Osborne Gordon and John Ruskin. A wreath was processed to the Sanctuary and placed at the foot of Ruskin's memorial epitaph to the Rev. Osborne Gordon, "rebuilder of this church".

Stained-glass windows chronologically

The Life and Death of Talitha by William Wailes. Photograph by kind permission of the Rev. Guy Cole.

The two-panelled west window in the north aisle, showing scenes from the life and death of Talitha, the only child of Jephthan and Jairus, is probably the earliest. It was made in memory of seventeen-year-old Georgine Samuel by the firm of William Wailes about 1867, the year of the re-consecration of the new church. It is interesting to note that some of the foliage borders depicted in this window remain as outlines on plain glass. The reason for this is unknown, but it may be an echo of the design of the original plain glass.

The south window in the Downshire chapel, depicting acts of charity, with the Good Samaritan and the text "Go and do thou likewise" in the central panel, is also by William Wailes and dates from 1868, in memory of Arthur Hill, the 4th Marquis of Downshire, who died that year.

In the baptistery, on the west wall, the cross-shaped stained-glass window depicting the baptism of Christ, again by William Wailes, was installed in 1873. The main panel depicts the baptism of Christ, above which are Saint Matthew, and the symbols of the other evangelists saint Mark, Luke and John, surrounding the dove representing the descent of the Holy Spirit. Once again, traces of plain glass are visible.

The one-light south window in the baptistery is by Michael O’Connor and Sons. Although it is undated, it probably dates from the 1870s according to David Gouldstone. The words engraved "Jesus the Good Shepherd" express the subject matter. Dublin-born Michael O’Connor died in 1867, but his three sons carried on the business.

The south chancel window, depicting the ministry of the angels in the life of Jesus, was made by James Hardman & Co. in 1874. Below the roundel of an angel holding a palm, the main scenes are the Annunciation, Joseph’s dream to flee into Egypt, Gethsemane and the empty tomb.

The following year, 1875, Hardman & Co. made another window in the chancel, this time the westernmost window on the north side. It depicts Saint Michael on the point of spearing and defeating the Devil.

The East Window by Morris and Burne-Jones. Photograph by kind permission of the Rev. Guy Cole.

The masterpiece in the church is the huge east window (1876) by Burne-Jones and William Morris. Osborne Gordon was determined to have the finest possible glass, design and craftsmanship, particularly for the great East Window. He informed Ruskin of the outcome of his negotiations in a letter of 11 June 1874: "Morris & Co. are going to do the East Window in my Church and I have no doubt it will be a success" (Ms L7,Lancaster). The project had been the subject of previous correspondence in which Ruskin had challenged Gordon about his expenditure on works of art. Gordon defended himself and wrote to Ruskin: "I must undeceive you as to what you said about my 'spending my money on bad art'. I spend none on art good or bad – but only on things necessary – £5 is all that windows have cost me – and I have never asked any one for a farthing. But I have not refused to allow other people to do what they offered – and have only done the best according to my light – which is perhaps very like darkness" (Ms L7, Lancaster).

The magnificent east window was financed by the lady of the manor, Georgiana (née Balfour), Marchioness of Downshire, as a result of a personal tragedy, in memory of her young husband, Arthur, fifth Marquis of Downshire who had died at the age of twenty-nine on 31 March 1874. The foremost artist of the day, Edward Burne-Jones, produced designs for the subject, The Last Judgment. A preliminary pen-and-ink design, now in the Royal Academy of Arts collection, London, is dated June 18, 1874. Burne-Jones’s cartoon of The Last Judgment is housed in his home city, in the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery (ref.1898P19 Burne-Jones 178-79).

The east window is composed of three lights surmounted by a sexfoil rose window Dies Domini, the Day of the Lord. The central light shows the warrior Michael, Archangel and Saint (an appropriate subject for a church dedicated to him) dressed in a short tunic and holding in his left hand a balance scale in which the souls of the departed will be weighed in judgment, and a spear in his right hand. Angels blowing straight trumpets are depicted in the panels on each side.

Left: Mary Magdalene. Right: Mary Magdalene and the risen Christ. Photograph by kind permission of the Rev. Guy Cole. [Trumpeting Angels]

A two-light window (1878) depicting scenes of the Resurrection and St Mary Magdalene on Easter morning, below a quatrefoil, the work of the Burne-Jones and Morris partnership, was placed above the altar in the area known as the Resurrection Chapel on the east side in the north aisle. The left light shows Mary Magdalene, clutching her robe in an attempt to find comfort, and an angel seated on the slabs pointing to the empty tomb. In the right-hand light, Mary Magdalene kneels, holds her hands with her palms upwards and gazes at the risen Christ standing before her. The story is told in St John 20:11-18. Above the two lights is a quatrefoil framing two angels blowing straight trumpets (a favourite motif of Burne-Jones and one which echoes The Last Judgment window). The white and pale yellow robes of the six figures predominate against a background of shades of green in the rocks and foliage. These windows were commissioned as a memorial to W. J. Scott of Wick Hill House, Bracknell, who died in 1875. They date from 1878.

The two-light south window of the south aisle dates from some time before 1879, and was made by the firm Lavers, Barraud & Westlake. It shows the parables and miracles of Christ. In the left light, are the parable of the sower and the miracle of Jesus turning water into wine at the marriage in Cana; in the right-hand light are the parable of the talents and the miraculous draught of fishes. All the scenes are framed by dense colourful foliage.

The two-light west window in the area beneath the tower is also by Lavers, Barraud & Westlake and dates from 1879. The two main panels depict two Old Testament stories of benediction beautifully framed with colourful foliage: on the left, Joseph is presenting his sons Ephraim and Manasseh to his blind father Jacob for a blessing; on the right, Hannah presents her son Samuel to Eli the priest for his blessing. In the quatrefoil above, Moses is holding the Ten Commandments.

Westlake's windows were the gift of local resident John Thaddeus Delane, former editor of The Times who died in 1879. At Delane's funeral in November, Gordon made a particular reference to his generous gift in his homily (Simon 8).

The two-light window (1883) in the north wall of the north aisle depicts the Martyrdom of St Maurice who, according to the story, was an Egyptian-born Roman soldier executed by the orders of Emperor Maximian for refusing to allow his men to participate in slaughter or worship Roman gods. This work by Burne-Jones was executed in the year of Osborne Gordon’s death: we do not know the exact month of completion or whether Gordon ever saw the finished product.

Other embellishments to the church overseen by Osborne Gordon

In addition to the production, supervision and installation of these stained-glass windows, not forgetting the disruption the work must have caused, other important works were being carried out under Gordon’s authority.

The organ: It was noted at the time of the re-consecration of the new, but incomplete church in 1867 that, in the architectural plan, "the chancel and a south aisle [had been] set apart as a vestry and organ chamber". One can assume that the music for the ceremony had been provided perhaps by a piano or simply by the choir alone. Organs are expensive items and some of the money collected at the offertory would have contributed to the purchase. It was not until 1869 that an organ, built by J. W. Walker and Sons, was installed in the space between the choir and the sacristy. This famous firm was also responsible for the organ in newly restored St Leonard's Church, Bridgnorth. It is noteworthy and commendable that this specialised firm still flourishes in the twenty-first century, with bases in Suffolk and Wiltshire.

High Altar Reredos, 1873: At the time of the re-consecration, mention was made of "the central panel of the reredos, [with] a large cross of red Devon marble, which will eventually be surrounded by carved symbols of the Evangelists and a device in rich mosaic and malachite". So the plan had already been decided by 1867: it was not until 1873 that it began to be executed. The central panel, depicting the Crucifixion, was designed by Harry J. Burrow (died 1883). The following entry concerning this Opus Sectile Reredos central panel can be found in the order book of James Powell & Sons of Whitechapel, east London: "Feb.[ruary] [18]73 Easthampstead, Bracknell. Reredos designed by Burrow [Probably painted] Crucifixion" (Tiles). The outer, side panels of this high altar Reredos depicting the four Evangelists with their attributes were designed by Henry Holiday (1839-1927) and installed in 1877. The cost was £82, approximately equivalent to over £9000 in 2020. The entry in the order book of James Powell & Sons is the following: "Sept 1877 Easthampstead, Berks. Reredos. 4 panels of opus sectile. Cash book p. 120 five figures of Evangelists and their emblems (Holiday) [From designs for window at St Matthew, Upper Clacton] £82" (Tiles).

In 1905, James Powell & Sons also manufactured the Reredos panel depicting the Walk to Emmaus, designed by John W. Brown, placed behind the altar in the chapel (often called the Resurrection Chapel) in the north aisle. The entry in the order book is as follows: "24/3/05 Easthampstead, Berks Reredos panel, N. aisle. Walk to Emmaus. Design by Brown £8-15-0 100 guineas" (Tiles).

Henry Holiday. Albumen print by an unknown photographer. 1870s.

Henry Holiday was a prolific artist, stained-glass designer and sculptor who moved within and without the Pre-Raphaelite circles: his friends and acquaintances included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Walter Crane, Lewis Carroll, Simeon Solomon and Arthur Moore. From the early 1860s, he was the main designer of stained glass for Powell & Sons. His link with Ruskin is of particular interest to us. Ruskin helped and befriended the young artist, introduced him to Burne-Jones, and in his autobiography, Holiday also recalls several visits to the older Ruskin at Brantwood and their stimulating conversations, especially in the summer of 1890 when Ruskin was much mellowed in his opinions about Herbert Spencer, about which Holiday recalls: "The conversation was deeply interesting to me, and very touching" (358).

By the end of the nineteenth century, the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene was endowed with some of the finest stained glass in the country, mainly due to the efforts and influence of Gordon. The embellishment continued under the supervision of subsequent rectors, and continues to this day. The most recent stained-glass window, in the entrance porch, is the representation of the Baptism of King Cynegils by Saint Birinus by the English artist Thomas Denny (born 1956), unveiled by businessman John Nike on 9 June 2013.

In the second, revised edition of Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire, published in 1872, the travel writer Augustus Hare described the new church as being "in a mixed Byzantine and Early English style". Byzantine features in the church at that time were the peacocks, regarded as an emblem of the resurrection and a favourite form in Byzantine art: a Byzantine feature introduced into the church later was the stunning mosaic in front of the high altar. Mention is made of a "noble yew-tree, 63ft in circumference" (32) growing in the churchyard, an impressive tree still alive in 2020. Murray’s Architectural Guide to Berkshire of 1949 was critical:

the church was rebuilt in 1866-67 in a style that combines late thirteenth century English and Byzantine characteristics from designs by J.W.Hugall. The result is (as Meade Falkner’s version of Murray’s Handbook rightly calls it) ‘pretentious’ rather than original or successful. No doubt it shows an attempt on the architect’s part to think in an impressive, personal style but he surely thought too much and felt too little. Much Italian marble and carved oak are used in the heavy fittings. [Collins 31-32]

Hugall, from Easthampstead church to Stanmore Hall, near Bridgnorth, Shropshire

John Pritchard MP. By permission of Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury.

As befitted his rising status and needs, Osborne Gordon’s brother-in-law, John Pritchard, acquired extensive lands and property around the Broseley/Bridgnorth area, as well as a prestigious London address at 89 Eaton Square. On the death of his childless brother George, in 1861, he inherited Stanmore Grove, a somewhat dilapidated and neglected country property near Bridgnorth. It was described unflatteringly in a letter to Eddowes’s Shrewsbury Journal of 28 February 1866 by one of Pritchard's opponents who signed the letter ‘Turn-him-out’, Bridgnorth’ as "a very mean-looking square-built brick house, the front facing due east, the north overgrown by closely approximating fir trees . . . the south with a tolerable view towards Bridgnorth, and the west, or back door, opening immediately upon the mixens of Mr. S. Ridley’s farm-yard" (8; information kindly supplied by George C. Baugh). It appears that John Pritchard never lived at Stanmore Grove, partly because it was in such a dilapidated state. It was described as "unlettable" and its only occupants being Mr. Richard Boycott, son of John Pritchard’s late partner, and "a domestic". The house was known locally as "Gitton’s Folly", before John Pritchard came to own it because of a mortgage of the Bridgnorth solicitor Gitton.

However, a dispute over the coming of the railway was instrumental in changing Pritchard’s opinions of Stanmore Grove. The encroachment of the developing railway network through the countryside in the nineteenth century was as familiar to Ruskin as it was to Pritchard who found himself in the midst of a dispute. He had at first publicly supported the development of the Bridgnorth, Wolverhampton & Staffordshire Railway at a public meeting in Bridgnorth in May 1865. But, much to the anger of local people, he changed his mind and became known and mocked as "chamelion" John Pritchard. He alleged that the railway would pass within 100 yards of Stanmore Grove, destroying "its beauty, comfort, and privacy" and so unfitting it for his habitation. Perhaps realising that he would be in a stronger position to resist any further attempts to encroach on his estate if he resided there, Pritchard decided to radically transform Stanmore Grove into a most desirable residence in the heart of his constituency.

So, on the very satisfactory completion of Easthampstead church by Hugall, this architect was engaged to alter, extend, refurbish and transform Stanmore Grove into the magnificent, palatial, Italianate Stanmore Hall. The mainly Georgian Stanmore Grove was extensively altered, refurbished and extended in 1868-70 to become Stanmore Hall, with advice from Ruskin (SA, Shrewsbury, [Dr R. H. Moore], “The Pritchard Family and Businesses.” Pitt & Cooksey 1190/3/1 – boxes 39-41 & 64-85). Hugall was essentially a church architect and the domestic, secular architecture of Stanmore presented a different kind of challenge. He accepted the commission soon after completing the church of St Michael and St Mary Magdalene at Easthampstead to the satisfaction of Pritchard's brother-in-law, the Rev. Osborne Gordon. Gordon’s ethos of having the very best craftsmen and materials permeated Stanmore Hall.

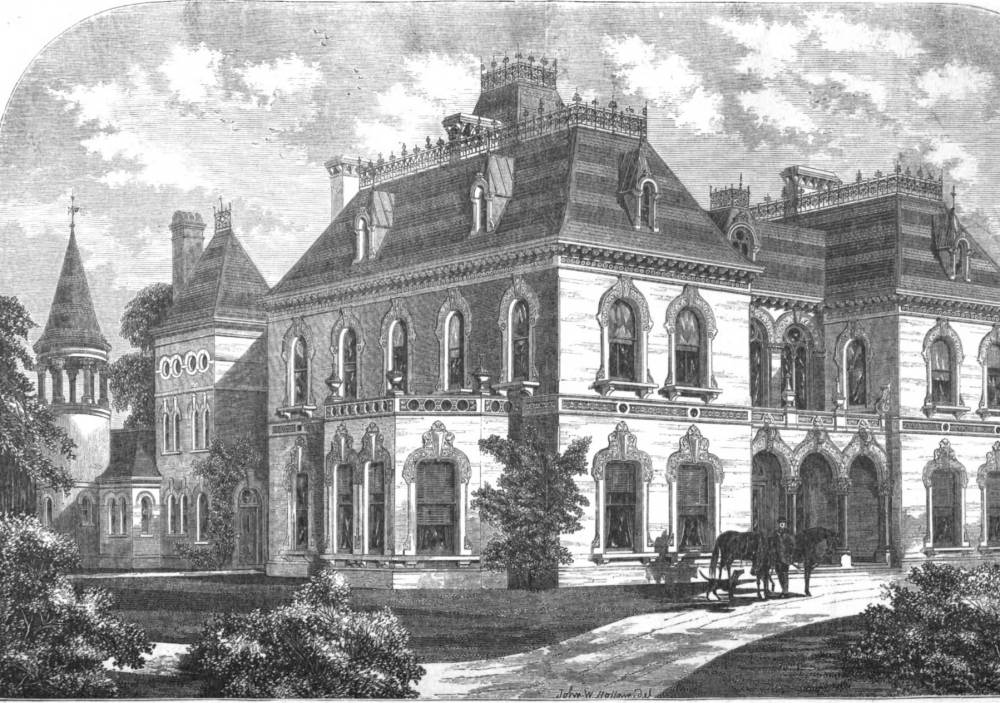

Stanmore Hall Bridgnorth. J. W. Hugall, Architect. Online version of The Builder provided by Hathi Trust Digital Library from a copy at Columbia University.

The completed building featured in The Builder of 1 October 1870. An illustration by John W. Hallam, engraved by W. E. Hodgkin, shows Stanmore Hall resplendent as a French Renaissance château with roofs surmounted by wrought-iron cresting and finials, dormer windows and roof lanterns, decorated parapets, balustrades, and turrets. It has a symmetry that is associated with the châteaux in the Loire Valley. The windows on the ground and first floors have features of Venetian Gothic. A black and white photograph of an interior gallery, circa 1897, illustrates the Gothic aspects ( SA, Shrewsbury, ref. PH/W/33/103). It was strikingly polychromatic, constructed of red brick and covered with red and blue tiles, arranged in lines. Specialist companies were engaged from all over England to provide the finest materials and fittings. As well as aesthetic considerations, comfort was paramount. Modern conveniences were installed – mains water and gas, a central heating system by means of hot water, a luggage lift reaching from the basement to the attics, a bathroom and three separate toilets on the first floor, together with two more toilets on the ground floor. There were nine bedrooms, three dresssing rooms, a nursery (a surprising inclusion for the Pritchards were childless), an upper hall and Jane Pritchard's own south-facing sitting room on the first floor. Downstairs were the servants' quarters, housekeeper's room, hall, drawing room, dining room, morning room and a library. Eric Mercer regarded Hugall's design as "adventurous" and "eccentric" (Mercer 227) because of an unusual feature – the ground floor butterfly wings on the northwest side extending off the servants' hall and a scullery. Standing in front of the main triple portalled entrance in Hallam's illustration is perhaps the châtelain himself, John Pritchard with his black horse and dog, about to go riding on his 1,300-acre estate.

Here is a description of Stanmore Hall in the The Builder for the first of October 1870:

This house, of which we give an illustration, has recently been erected on the estate of Mr. John Pritchard, near to the picturesque town of Bridgnorth, Shropshire, under the direction of Mr. J.W. Hugall, of Oxford.

The site selected is very high, and the grounds are beautifully varied with an extensive view across the Severn valley, along which the river is seen to flow at various points.

The house is built of pressed red brick from Broseley, with Bath stone dressings, and is covered with red and blue tiles, arranged in lines. The flats are covered with Vieille Montagne zinc, by Fox; and the cresting and finials, of wrought iron, surmounting the roofs, together with the gas-fittings, balustrading, and coil cases, are from the works of Messrs. Thomson & Co., of Birmingham; Messrs. edwards, of Great Marlborough-street, fitted up the hot-water apparatus, the culinary arrangements, and the laundry; Mr. Coalman, of St. Mary Church, near Torquay, supplied the marble mantel-pieces, slabs, inlays, and columns; Mr. Steinitz laid down the parquetry in the entrance-hall; Messrs. Jackson executed the very elaborate ceilings in their fibrous plaster; and the general contractors, Messrs. Wall & Hook, of Brimscombe, have carried out their various works with care. Water and gas have been laid on from the town of Bridgnorth, a distance of two miles.

The principal and some subsidiary rooms have a line of hot-water pipes passing through them, and coils are placed in the halls, covered by wrought iron and brass cases with marble slabs. A lift for luggage reaches from the basement to the attics. The principal staircase is of oak and enclosed beneath, to form a serving passage to the dining-room.

The house being erected on a slope of the ground to the north, advantage has been taken of it to form a basement for laundry, larders, cellarage, and so on.

A considerable quantity of stone carving is executed both externally and internally. [784]

John and Jane Pritchard lived there in style, entertaining lavishly. John Pritchard acquired considerable wealth. In 1883, he owned 3,254 acres worth £5,123, land acquired by his family over the previous 40 years, and who "were too recently landed to be in county society".

John Pritchard died in 1891, at the age of 94: his wife died the following year.

Destiny of Stanmore Hall

Stanmore Hall was bequeathed to Jane’s nephew, William Pritchard Gordon, the son of William Pierson Gordon (c. 1822-1888). William Pritchard Gordon also inherited an impressive art collection of works by or acquired on the advice of Ruskin, and extensive lands with a rental income of over £1,900 p.a.(SA, Shrewsbury, [Dr R. H. Moore], “Pritchard Family and Businesses”, Pitt & Cooksey, 1190/3/1.) Since he already owned and lived in a large residence at Danesford, near Bridgnorth, he let Stanmore Hall to Frederick St. Barbe Sladen (c. 1842-1923), (resident at Stanmore Hall according to the 1901 England Census). In Kelly’s Directory of 1900, W. P. Gordon is described as one of the principal landowners of the parish of Worfield and of Chetton. Like his uncle, he was a respected Justice of the Peace and actively involved in the life of the community. In a sale catalogue printed for the auction of Stanmore Hall to take place at the Star & Garter, Wolverhampton on 20 October 1920, the Hall was described as "decorated in the Italian style" (SA, Shrewsbury, ref. 1190/3/567/1). W. P. Gordon's eldest son, Herbert Pritchard-Gordon (by now the name is hyphenated), disposed of the fine art collection at a sale at Sotheby's on 10 May 1933. Homage was paid to John Ruskin in the catalogue in the preface to the list of sixty-five sale items:

The Property of H. Pritchard-Gordon, Esq. Berrington Hall, Shropshire. This Collection was formed by Mr. Gordon's Great-great Uncle, J. Pritchard, Esq. of Stanmore Hall, Bridgnorth, Shropshire, and was bought under the guidance of John Ruskin, who was a close personal friend.

Considerable changes took place to Stanmore Hall over the next few decades. The saddest change was the destruction announced in a demolition sale to take place on 5 May 1925 (SA, Shrewsbury, ref. MI973). Pritchard's magnificent residence was then briefly described as "an imposing building in a distinct (chateau?) style, with striped tiling and complex fretwork to the roof, a croquet lawn in the foreground and two small towers in the background to the left".

Almost a century after Pritchard's former Venetian Gothic residence had been so splendidly described in The Builder in 1870, it was almost unrecognisable. The Catalogue of the sale of Stanmore Hall by Ian Haynes & Co., Halesowen, on the instructions of Mr and Mrs Jeffrey Hickman, advertised the Hall as a "period Gentleman's Country Residence [...] fully centrally heated and completely renovated regardless of expense [and] one of the most attractive Georgian style individual properties in the area". No vestiges of Gothic are apparent in the photograph of the house. Stanmore Hall was partly demolished again in the mid-twentieth century; the massive wings housing servants were removed and the five-bay main block reduced to three bays. The coach houses were converted to cottages. A motor museum was created, and later a caravan park (still in existence in 2020) in the extensive grounds. The grounds of Stanmore Hall were the site of a Royal Air Force camp during the Second World War.

Last modified 10 March 2020