In the summer of 1975 I was on holiday, staying in a caravan in the Lake District. I’d been reading about Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, and had encountered Ruskin as part of those stories; so when I chanced upon a second-hand bookshop, it was a natural thing to inquire if the bookseller had anything by Ruskin. ‘Over there,’ he said, indicating a dusty cobwebby corner. ‘Do you have a wheelbarrow?’

Left: The Ruskin Review and Bulletin. Middle: Alan Davis and Van Akin Burd at the Ruskin conference held at Lancaster in 2000. Right: The cover of Ruskin and the Persephone Myth, a 2007 exhibition at the Ruskin Library. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

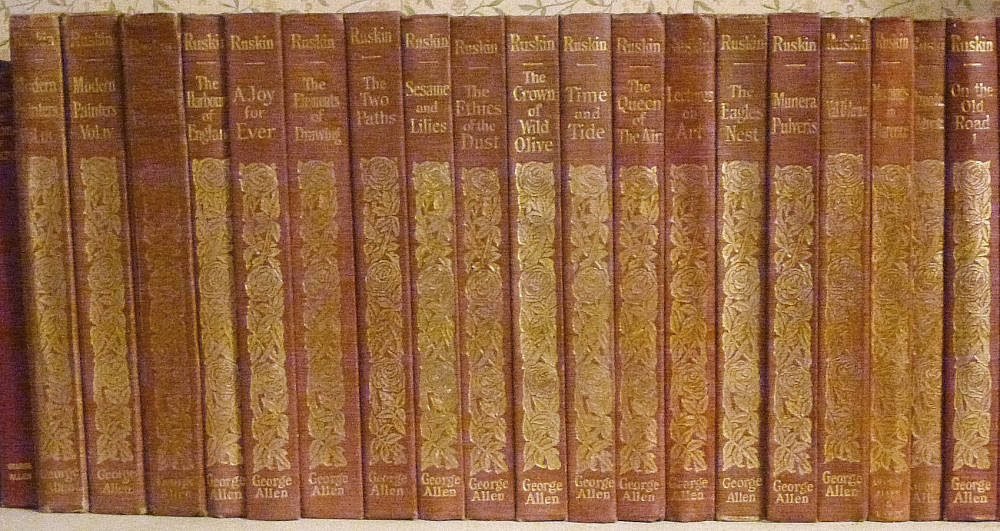

There were shelves full of Ruskin in that corner – mostly the small brown and green George Allen editions – marked at ridiculously low prices because nobody wanted them. I had no wheelbarrow, but I bought an armful and staggered out of the shop. Back at the caravan, I sifted through my collection, selected Mornings in Florence, and began to read. I had never been to Florence and knew almost nothing about Italian art, so I found myself reading about places I’d never visited, artists I’d never heard of, and paintings I’d never seen. But I was captivated, and I did not have to read many pages before I realised that I’d found a companion for life.

After that I bought all the Ruskin I could find and, armed with the five volumes of Modern Painters (six if you include the Index), proceeded to explore the extensive landscape of nineteenth-century British art with Ruskin at my shoulder, pointing the way. As the years passed, Ruskin’s voice became a permanent part of the background to my thinking, and I learned to enjoy that mysterious sense of intimacy which long experience of reading a much-loved author can bring. It was not that I found him infallible – on the contrary, I often found him mistaken or downright silly – but his perception was so acute, his use of language so vital, and above all, his companionship was so enriching.

It never occurred to me that my Ruskin passion was more than a purely personal interest, until in 1993 I learned about Michael Wheeler’s ‘Ruskin Programme’ at Lancaster University, just a few miles from where I live. He invited me to join the weekly Ruskin Seminar, and that determined much of the tenor of my life for the next 25 years.

Last modified 2 May 2019