Left: Cover of the book under review. Right: Tenniel's cartoon of the previous week, presupposing the rescue of General Gordon (Punch, 7 February 1885: 67). Click on these and the following images for larger pictures.

The front cover of Neil Hultgren's Melodramatic Imperial Writing features a cartoon by John Tenniel from the Punch magazine of 14 February 1885. Captioned "Too Late," it refers to hostilities in the Sudan, and shows the familiar figure of Britannia reacting extravagantly to news of General Gordon's death. The imperial hero had been killed just before the relief force arrived at Khartoum where the British were entrenched. Ironically enough, the magazine had run another Tenniel cartoon just the week before, anticipating a happier outcome, and captioned, "At Last!" Hultgren uses the pair to show how "the melodramatic mode and representations of late-Victorian British imperialism converge" to express popular feeling (1-2). Melodrama, he argues, with its potential for unexpected turnabouts, of heroes into villains and triumphs into disasters, afforded authors from Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins onwards, right up to Olive Schreiner at the end of the nineteenth century, opportunities to grapple with "the British Empire's representations, validations, and justifications of itself" and to rethink "imperialism's function and rationale" (4). Along with a range of Victorian fiction on the theme, Hultgren looks at the poetry of W. E. Henley and Rudyard Kipling.

Although Hultgren traces the origins of melodrama back to its eighteenth-century roots, he avoids giving it any precise definition. Rather, he treats it as a "cluster concept," recognising it through its propensities for "providential plotting, emotionality, and sense of community" (11). None of these elements is, in itself, unique to melodrama. But, taken together, and in conjunction with the mode's theatricality, they do seem to comprise an entity or at least a mode. It is one, moreover, ideally suited to presenting the clash of powers, the rise and fall of colourful historic figures, and the public hysteria often attendant on these events. On the other hand, being so clearly an overheated response, melodrama can also provoke counter-reactions. For example, when looking at Tenniel's second cartoon, the more cynical might remember that Gordon was meant to have evacuated the troops from Khartoum long ago, and that Gladstone in turn had withheld relief until growing pressure from both Queen and public had forced his hand. Seen from this point of view, Britannia's display glosses over unpalatable truths about British mismanagement. Hultgren goes one step further, suggesting that Tenniel has acknowledged and compensated for all this with a "climax of grand allegorical pathos and mourning" (2). Despite or even because of its resistance to precise definition, therefore, Hultgren is able to throw light on melodrama and its uses, and also on attitudes to empire in individual works and authors.

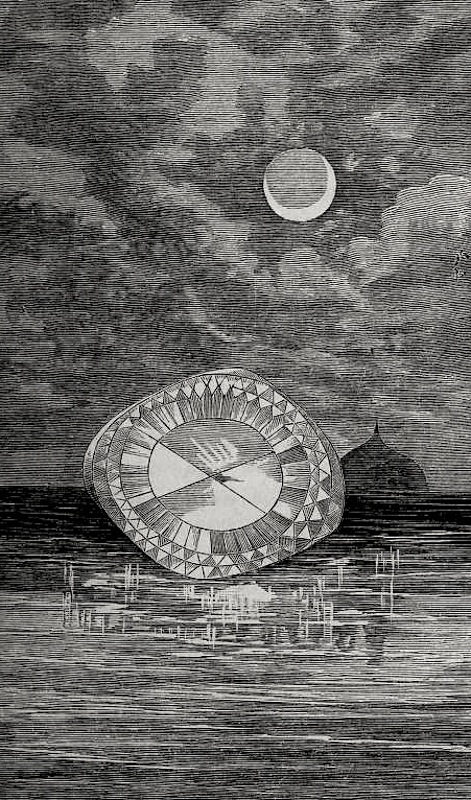

"The Moonstone," seen here as very much a cosmic force (Collins 129).

Part One deals with "Melodrama as Plot." The first chapter here discusses "providential plotting" in the story, "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners" (1857), by Dickens and Collins, and Collins's much better-known full-length work of 1868, The Moonstone. Providential plotting is one of Hultgren's key concerns. Looking at the variety ways in which providence is seen to operate in such narratives, he argues that it reflects a variety of ways of discussing the relationship of the empire with its far-flung subjects. "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners," for instance, though deliberately set elsewhere — on an island off the Honduran coast — envisions a happier outcome for the kind of situation that ended in the tragic massacre of men, women and children at Cawnpore during the Sepoy Rebellion. On the other hand, in The Moonstone, Collins banishes the element of wish-fulfilment, replacing it with a very different mystical force, this time on the Indian side — that is, the curse that follows the misappropriated jewel and leads to it recovery. The traveller Mr Murthwaite, and the detective Sergeant Cuff, both try to reduce the events surrounding the jewel to reason, but they cannot in the end undercut its own efficacy. Indeed, Murthwaite himself senses the moonstone's strange powers. In this way, says Hultgren, the novel "posits a Hindu alternative to the calls on Christian providence that proved central to Dickens and Collins's early response to the Sepoy Rebellion" (61). The "Hindu alternative" may seem alien, but has its own justice, and Collins's appreciation of this tells us much about his breadth of sympathies. By contrast, Hultgren's next chapter, on Rider Haggard's Jess: A Novel (1887) and Marie Corelli's tale of the occult Ardath: The Story of a Dead Self (1889), explores a more grandiose view of empire. Both novels are considered as "idealist renderings of the imperial romance," each in its own way demonstrating how the "providential plotting and poetic justice of the melodramatic mode" were used in an attempt to "spiritualize" the empire (88), and so make it appear a divine destiny. Corelli's extraordinary revision of imperial history seems particularly hubristic now.

"'This is the bottle,' said the man": the central character Keawe's first glimpse of the mysterious bottle in Stevenson's "The Bottle Imp" (Stevenson 154).

In Part II, on "Melodrama as Aestheticized Feeling," Hultgren has to work harder to convince. The first chapter here deals with melodrama's "reliance on excessive forms of emotion" (93) in the imperialistic poetry of W. E. Henley and Rudyard Kipling. He sets the scene well, with a useful introductory section on the larger-than-life playwright and Drury Lane theatre-manager, Augustus Harris, one of the inspirations for these poets' particular brand of patriotic bombast, and reminds us too of Henley's links with Oscar Wilde as well as with Kipling. It is not such a surprise, then, when Hultgren gives this poet the unlikely label of an "Aesthete of Action" (98). Hultgren is not the first to try to associate Henley with aestheticism, but perhaps the first to do so on the basis of his indulgence in "the aesthetics of melodrama" (109). Yet since Henley himself once wrote, "I have never babbled the Art for Art's Sake babble" (qtd. 100), the attempt still feels a little forced. The same may be said in the case of Kipling. Hurtgren admits that he "became conscious of the strategic value of opposing himself to aestheticism," but nevertheless draws him into the fold on the grounds that he adopted "the aesthetics of melodrama" (109). Similarly forced is Hultgren's treatment of Robert Louis Stevenson in the next chapter. Stevenson had collaborated with Henley on stage plays, and shared his predilection for melodrama. But "aestheticized feeling" seems even less appropriate a label here, in view of Stevenson's reaction against over-emotionalism. This is in his writings about Hawaii. The over-emotionalism in question is not so much Stevenson's own, but that of the indigenous people, whom he felt lacked "healthful rigour" in their propensity to disobey quarantine requirements for relatives afflicted with leprosy (qtd. 129). Hultgren examines Stevenson's tale of 1891, "The Bottle Imp," to show how he used "the melodramatic mode ... as a unique aesthetic tool" (emphasis added) to enable him to react appropriately to such "excessive emotion in the Pacific" (151). Apart from being oddly expressed, this seems rather a tortuous way of aligning him with aestheticicm.

The appropriately aspirational front cover of Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm (1883).

Part III of Melodramatic Imperial Writing focuses more usefully on Olive Schreiner, taking up in particular The Story of an African Farm (1883), a novel that has, Hultgren assures us, often been seen as "a critique of melodramatic aesthetics" (166). The outrageous figure of Bonaparte Blenkins does lend itself to such an approach, especially since he implodes after having been revealed as an impostor, and is ejected from the farmstead. But Hultgren proposes another reason for the fading out of melodrama here: the isolation of Schreiner's characters on the vast expanses of the karoo. After describing how the heroine, Lyndall, talks to herself in the mirror, Hultgren writes:

In such moments, the second half of The Story of an African Farm emphasizes the melodramatic mode’s dependence on place. The novel contextualizes melodrama’s power and meaning, pointing out the limitations of the melodramatic mode. Because melodrama depends on larger communities and draws on their social, national, and familial discourses, it is not an aesthetic that can be readily imported from the metropole to isolated and far—flung locales without losing much of its emotional and ethical impact. [182]

This is an interesting point, even if it is introduced awkwardly. Hultgren goes on to demonstrate that Schreiner writes more melodramatically when she addresses a British middle-class audience in her later political writing: the last part of the chapter deals with her skit, "The Salvation of a Ministry" (1891), in which she depicts Cecil Rhodes as being too large to fit into hell at the time of the Last Judgement, and therefore being admitted to heaven by default. As Hultgren maintains in his conclusion, melodrama has continued to be useful for describing and questioning the colonial period, and also its aftermath. As far as "excessive emotion" goes, however, the dominant mode outside the academic speciality of post-colonialism (in Britain at any rate) is probably nostalgia.

Hultgren is fond of giving melodrama its own agency. Despite not having defined it clearly, he grants it not only its own kinds of plots and its own "harmony with imperialist discourse" (188), but also (somewhat contradictorily) its own sometimes "fraught ideological position in relation to violent imperialism" (3), its own "Manichean logic" (107), and, as we have seen, its own aesthetics (109). The authors themselves often seem to be left out of this set of equations. Critics, on the other hand, are very much present, making this a dense and overly challenging read. At the end of Part One, for example, Hultgren admits that his "discussion of melodrama, imperialism, and providential plotting in Haggard and Corelli overlaps with models for understanding late—Victorian literature of empire by Patrick Brantlinger in his comparison of occult realms and the imperial periphery, Stephen Arata and his consideration of reverse colonization, and Jeffrey Franklin in his theory of the "counter-invasion" of Buddhism," but adds that "the emphasis on incident taken [by himself?] from Andrew Lang suggests that late—Victorian writers of the imperial romance plotted the development of the British Empire in ways that are not reducible to these compelling models (88). He goes on to mention several more names before relating Corelli to Kipling, whose work has yet to be discussed. There are just too many "overlaps" and connections here. Hultgren's textual commentaries, for instance that on Henley's homo-erotic "The Song of the Sword," are never less than illuminating and stimulating. But it takes a certain amount of perseverance to reap their rewards.

Related Material

- The Imperial Context of "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners" (1857) by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Marie Corelli's Attacks on Realism in Ardath

- Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm As an Early New Woman Novel

Book under Review

Hultgren, Neil. Melodramatic Writing: From the Sepoy Rebellion to Cecil Rhodes. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2014. xi + 259 pp. $59.95 / £42.00. ISBN: 13 978-0-8214-2085-0.

Sources of Illustrations

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone, Part I (The Works of Wilkie Collins, Vol. 6). New York: P. F. Collier, 1900. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 2 January 2015.

Tenniel, John. Cartoons by Sir John Tenniel, Selected from the Pages of "Punch." London: Punch, 1901. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. Web. 2 January 2015.

____. Punch, 7 February 1885: 67. Wikipedia. Uploaded by Centpacrr. Web. 2 January 2015.

Schreiner, Olive. The Story of an African Farm: A Novel. Chicago: M.A. Donohue, 1883. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Web. 2 January 2015.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Island Nights' Entertainments. London: Cassell, 1893. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 2 January 2015.

Last modified 2 January 2015