THERE is no medium in photographs. They are either exceedingly beautiful, or — and this in by far the larger number of cases — exceedingly hideous. The beautiful has hitherto been often the accident of the inexperienced photographer. Experienced photographers nave often produced only hideousness in their copies of the human face divine. The reason, it seems, is, that a certain amount of experience is necessary to secure the exactness of the focus. An exact focus brings everything into the clearest outline, and so greatly emphasizes the bad drawing of the photograph. For all photographs are inevitably ill-drawn, the prominent parts of the images being exaggerated, and the receding diminished. The shadows of photographs are also always false, unless the original is colourless, or in one colour only; and, if these shadows have marked outlines, their falsehood is shockingly conspicuous.

But the emphasis which an exact focus gives to these great defects of the photographic image is scarcely more objectionable than the microscopic clearness with which it brings to the notice of the eye the minutest details, whether of defect or beauty; details that are merged, to the unassisted eye, which never does see objects in true focus, in a general impression, made up, indeed, of these elements, but of these elements seen with no obtrusive distinctness and isolating outline.

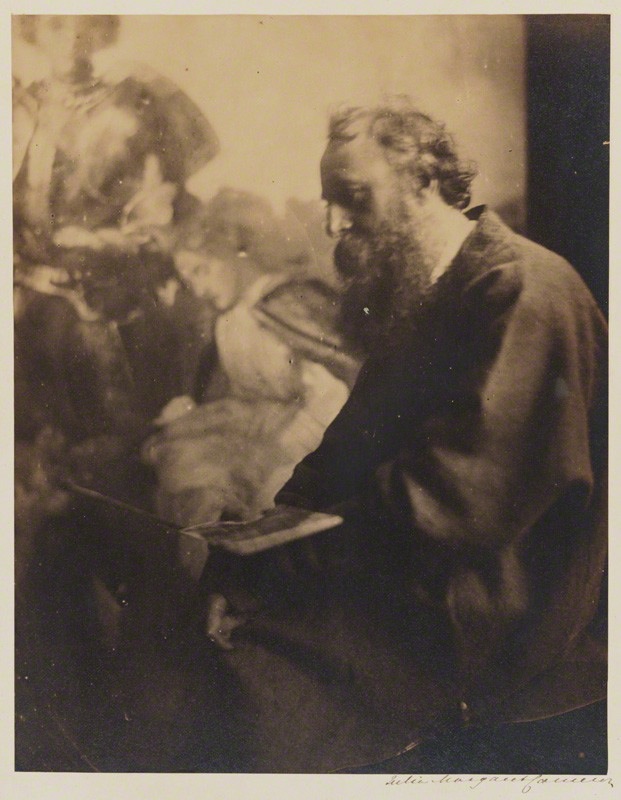

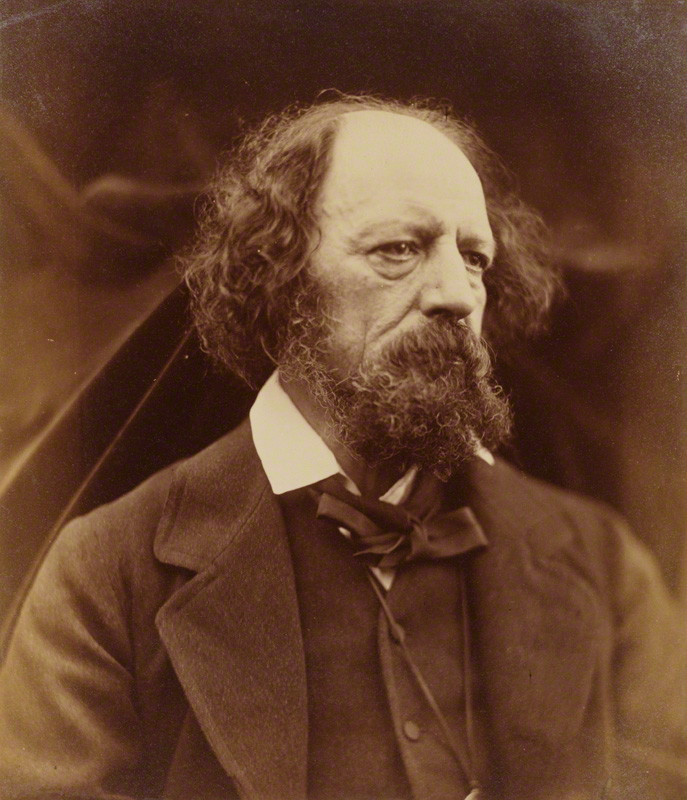

An amateur photographer, Mrs. Cameron, was the first person who had the wit to see that her mistakes were her successes, and henceforward to make her portraits systematically out of focus. But this has not been the sole secret of her unequalled art. She is evidently endowed with an unusual amount of artistic tact; she knows a beautiful head when she sees it — a very rare faculty; and her position in literary and aristocratic society gives her the pick of the most beautiful and intellectual heads in the world. Other photographers have had to take such subjects as they could get. With few exceptions, all Mrs. Cameron's subjects are of a very high order of beauty. But intellect and beauty have apparently not been the only qualities considered in her choice. She has carefully selected the beauty which depends on form. In the few instances in which the character of her originals has depended partly on colour, Mrs. Cameron's portraits are almost as unpleasant in their shadows as ordinary photographs are. Where there is little or no colour to interfere with the form, as in the heads of Mr. Tennyson, Mr. Henry Taylor, and Mr. Watts, the portraits are as noble and true as old Italian art could have made them ; but as soon as colour becomes an element of the character, as in the heads of Mr. Hughes, Mr. Holman Hunt, and some of the female subjects, the likeness is vitiated, and the ideality of expression, which is so remarkable in many of Mrs. Cameron's portraits, is altogether lost.

Three portraits by Cameron (not in the original article), all courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery: Left: G.F. Watts. Middle: Alfred Lord Tennyson. Right: Robert Browning. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

There is one point—a very trifling one in itself; yet one which may be very influential with persons unable to per ceive the higher qualities of the photographs exhibited by Mrs. Cameron—in which she seems to have done herself and her productions injustice. She has, in many cases, endeavoured to make pictures out of them. She is not content with putting one or more noble heads or figures on her paper; but she must group them into tableaur wivants, and call them “Faith, Hope, and Charity,” “St. Agnes,” “The Infant Samuel,” “The Salutation, after Giotto,” &c. &c. The effect of this is often strange, and sometimes grotesque; and must do much more to diminish the general popularity of the pieces which have such titles than any advantage, in the way of con venience of reference, can compensate. The simple human head is the only thing in which nature can rival art. It is impossible to compose, by juxtaposing, real figures, so as to emulate, in the faintest degree, the composition of great artists. Now the beauty of the heads in these photographs is the beauty of the highest art. We seem to be gazing upon so many Luinis, Leonardos, and Vandyckes; and the contrast between this “grand style,” which still remains in nature to the human head, with the postures into which the figures are sometimes forced, in order to make them into pictures “after Giotto,” is, in some cases, as striking and unde sirable as could well be. We are not sure, indeed, that the singular art with whith Mrs. Cameron has often arranged the draperies of her figures does not increase the effect of the “realistic" air which most of her groups persist in maintaining for themselves, after all has been done to bring them into the pure region of ideality.

It must have occurred to every thoughtful visitor of the collection at 120, Pall Mall, that the fact of the existence of such photographs ought to modify very greatly some of the prevailing theories concerning art. It will not do, as far at least as the human head is concerned, to speak any longer of ideality as the peculiar character of art. The greatest heads of the early painters were evidently nothing more than nature seen with an eye of perfect sincerity. The inference might seem to be that portrait painting is now at an end. But it is not so. Colour, in even the most colourless face, is a power which must be sadly missed in the finest photograph. Indeed, though it may sound paradoxical, it is usually in faces of the least colour that colour is the greatest power. Those who recollect the water-colour drawings exhibited, in the past season, by Mr. Edward Jones, must remember how some of his pieces, which were painted almost in monochrome, made the glaring drawings in their neighbourhood look almost colourless. A great colourist will give a greater effect of colour, literally without the use of a second hue, than can be obtained by an ordinary painter with all the colours of the rainbow. This wonderful power must never be laid aside, if we would have portraits of real value. The place of photography is that of a guide and corrector of the artist's eye, unless his eye be itself capable of photographic precision. By the aid of such photography as Mrs. Cameron's, an artist of moderate ability is enabled to produce such portraits as could otherwise be painted by none but excellent artists, and, by their aid, the excellent artists can arrive at a degree of excellence which has long been regarded as extinct. With such a power of portraiture as seems now to be within our reach, no beautiful head ought ever to be allowed to die. Beauty, though always springing up in new forms around us, is never reproduced. How many thousands of divine heads might each have been “a joy for ever,” had the ordinary powers of art been supple mented by such photography as that of Mrs. Cameron's.

We are glad to see that the exhibition which has been lately open in Pall Mall is advertised by Mrs. Cameron as her first exhibition. It is to be hoped that she will lose no time in working the mine which she may be said to have discovered. Meanwhile, we can affirm from our personal observation that her late exhibition has been admired in exact proportion to the artistic faculty and culture of the spectator.

Related material

Bibliography

Palgrave, F. T. “Mrs. Cameron’s Photographs.” Macmillan’s Magazine. 13 (1866): 230-31.

Last modified 30 November 2019