udyard Kipling and Edith Nesbit never met, but, at least to begin with, they admired each other's work. The evidence is there in print: Nesbit and her co-author, the journalist Oswald Barron (1868-1939), dedicated their short story collection, The Butler in Bohemia, to Kipling in 1894. Moreover, Nesbit wrote to Kipling in 1896 to enlist his support for a new children’s magazine that she was planning. He offered words of advice rather than promises: "a list of 'star' names is a snare unless and until you have 12 months good matter up your sleeve to carry on with" (Letters 1: 275), and indeed the project faltered. Still, Nesbit evidently kept him in mind, sending him copies of The Psammead (1903), The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904), and Oswald Bastable and Others (1905) when they appeared. Her first biographer, Doris Langley Moore, goes so far as to call her a "disciple of Kipling" (136). For his part, Kipling acknowledged all three of these early books gratefully, the first two at some length. In his response to the The Psammead, he signed off by saying, "I've been watching your work and seeing it settle and clarify and grow tender ... With great comfort and appreciation, Very sincerely Yours, Rudyard Kipling" (qtd. in "An Autograph Letter," 16). What more could Nesbit have asked for, from one of the foremost literary figures of the day?

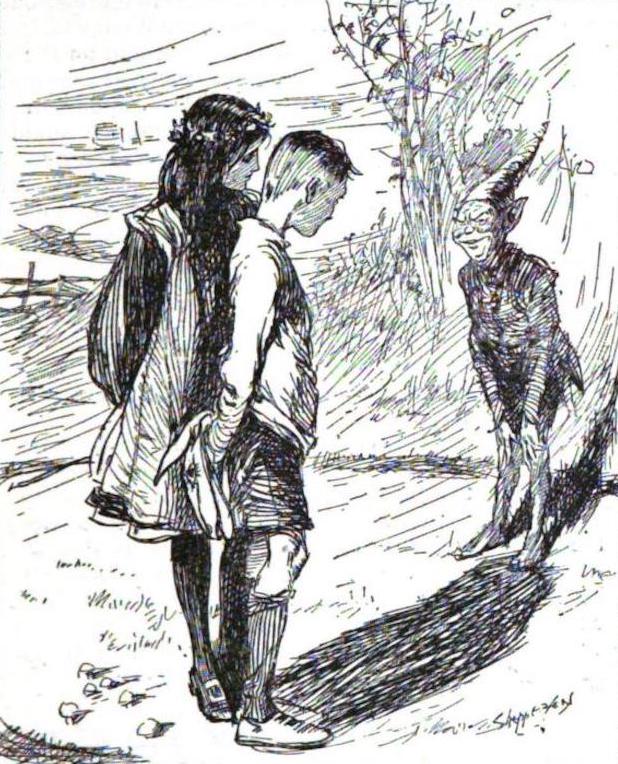

Two illustrations form The Strand Magazine. Left: The psammead pointing to the half-amulet which will be key to the children's visits to the past (Ch. I of "The Amulet" in Vol. 29: 599). Right: Puck laughing as Una and Dan look on (Ch. 1 of "Puck of Pook's Hill" in Vol. 31: 49).

After that, however, the relationship, such as it was, deteriorated for one of the worst possible reasons (for writers, at any rate). Both contributed to The Strand Magazine, and Nesbit suspected that, in writing Puck of Pook's Hill, Kipling had stolen her idea of time travel from The Story of the Amulet. The latter had been serialised in the magazine from May 1905, and the former from January 1906, just eight months later. In fact the two serialisations overlapped: the first chapter of Puck of Pook's Hill preceded Chapter 9 of The Amulet in the January 1906 issue by nearly sixty pages. There they were, side by side, for all to see the similarities, and they would continue in each other's company until Nesbit's last chapter ran in the May issue of that year. It left Kipling's work to run on alone until it completed its ten parts, in the October issue.

Nesbit not only suspected Kipling of plagiarising and making capital of her idea; she voiced her suspicions to both H. G. Wells and Barron. Her resentment was understandable enough. As Julia Briggs explains,

Her assumption that in The Amulet she had hit upon a highly original idea in sending her children into the past by magic was surely justified. Fictional children had tumbled down rabbit holes, visited fairyland, or gone small or swift — her own five had flown on a magic carpet — but time travel was another matter. Wells’s Time Traveller had explored the future, but not the past, and yet here was Kipling, some eight months after herself, using a sharp-tongued fairy not wholly unlike her own psammead to conduct two modern children into British prehistory. His timing, she felt, told its own story. [256]

Nevertheless, as Briggs herself is at pains to point out, there were precedents for such encounters with the past, in adults' literature if not in children's. Among these Briggs particularly focuses on Edwin Arnold's Phra the Phoenician (1891) and Lepidus the Centurion (1901), in which the past is explored through reincarnation, finding instances in their work of "Arnold's impact on them both" (258).

More telling, however, than this suggestion of common influences, are the obvious differences between Nesbit's and Kipling's approaches. Most notably, "[i]n Edith’s stories of time magic, the children travel directly into the past," while Kipling's Puck "brings people from the past to relate their experiences to Dan and Una in a dreamlike present" (Briggs 257).

Still more convincing is the matter of time, which seemed to clinch matters with Nesbit, but which, in fact, makes it almost certain that Kipling's ideas were conceived earlier. Here, Nesbit's most recent biographer, Eleanor Fitzsimmons, calls on earlier Kipling scholars: "experts suggest that Kipling was a slow writer and began Puck of Pook's Hill as early as September 1904" (177). Perhaps Briggs was one of the experts she had in mind, because it was Briggs who pointed out that Kipling, not only slow but prone to false starts, "is thought to have started Puck as early as September 1904 and to have written at least half of it before it began to appear in The Strand in January 1906" (256). Like Nesbit's original claim, this counterclaim (prefaced by "is thought to have") is vague and undocumented, but Briggs does refer us to Kipling's autobiography, Something of Myself, and this does more than record his discarded efforts. It shows unequivocally that the family's move to Bateman's in Sussex in 1902 triggered an intense interest in the ancient past, and inspired many forays into it: "The Old Things of our Valley glided into every aspect of our outdoor works. Earth, Air, Water and People had been — I saw it at last — in full conspiracy to give me ten times as much as I could compass, even if I wrote a complete history of England" (186-87). Here, more directly than any written source, was the inspiration for both Puck of Pook's Hill and its sequel.

But even if Nesbit had lived long enough to read this account, she might not have been impressed. Briggs points out that "by 1910 Hubert could chart 'The Decadence of Rudyard Kipling' in his newspaper column; Edith subsequently included the piece among Hubert’s posthumously published Essays." Suspicion had evidently hardened into certainty, and Kipling was not forgiven. Perhaps it was for this reason that, according to Moore in a footnote, "Kipling would not allow any of his letters to E. Nesbit to be reproduced" (187, n. 14) — though, as we have seen, some have since escaped that stricture.

There is an interesting footnote to this debate. As far as children's literature was concerned, whether or not Kipling owed a particular and unacknowledged debt to Nesbit's work, many later children's writers have adopted her approach — and have done so in her way rather than Kipling's. That is to say, they have involved their young characters in episodes from the past directly (in what are often now called "time-slip" plots) rather than bringing characters from the past into the children's present, almost in the manner of a pageant. Popular examples of this are Alison Uttley's A Traveller in Time (1939), and Philippa Pearce's Tom's Midnight Garden (1958), in which the protagonists "slip" back into the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries respectively. This was just one of the ways in which Nesbit's work for children "served as a model for many later writers" (Carpenter 374).

Bibliography

"An Autograph Letter from Rudyard Kipling from a Santiago, Chile, Bookshop." The Kipling Journal. (Vol XIV. No. 84. (December 1947): 15-16. (Back numbers of this journal are available online here.)

Briggs, Julia. A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit, 1858-1924. New York: New Amsterdam, 1987.

Carpenter, Humphrey and Mari Prichard, ed. The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. See 371-74.

Fitzsimmons, Eleanor. The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit. London: Duckworth, 2019.

Kipling, Rudyard. Something of Myself, for my friends known and unknown. London: Macmillan, 1937. Internet Archive. Contributed by Rashtrapati Bhavan, Delhi. Web. 30 July 2021.

The Letters of Rudyard Kipling. Vol 2: 1890-99. Ed. Thomas Pinney. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1990.

_____. "The Amulet." The Strand Magazine Vol 29 Jan-June 1905: 584-92. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Library of the University of Michigan. Web. 30 July 2021.

_____. "Puck of Pook's Hill." The Strand Magazine. Vol. 31 (Jan-June 1905): 48-56. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Library of the University of Michigan. Web. 30 July 2021.

Moore, Doris Langley. E. Nesbit: A Biography. Philadelphia: Chilton Company, 1966.

Created 31 July 2021