In 1883, the American poet Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) visited William Morris at Merton Abbey in Surrey. Three years later, her account of the visit was published in The Century Magazine. It appears here with the illustrations that accompanied the original publication. In addition to being a valuable first-hand portrait of Morris, Lazarus's report is of particular interest for its descriptions of the garden and workshop, and for a letter, appended to the original publication, in which Morris clarified his views on the labor and compensation of his employees. Click on the images to enlarge them.— DJ

William Morris

by Lisa Romana Stillman.

Engraved by J.H.E. Whitney.

arly in July the roses fairly run riot in the garden-like county of

Surrey; all along the railway the little village stations are walled

with thickly flowering vines, or hedged with blooming bushes. From one

of these small, bevined stations in a deep cutting of the Croydon road,

we started — a party of four — on a soft, gray midsummer morning for a

day at Merton Abbey.

Merton Abbey! the very name suggests visions of

venerable Norman arches and cloisters, the roofless aisles and topless

columns of some ruined seat of ecclesiastical power. In point of fact

the Abbey whither we were bound is merely a utilitarian factory that

supplies the marketwares for

Morris & Co.’s decorative art shop in

Oxford street. "'Tis five miles from Croydon, one mile from Wimbledon,"

Mr. Morris had said, in directing us where to find him; and we had

chosen to take the shortest part of the little journey by rail, and to

drive in an open carriage from Croydon to Merton. Here the enamored

Nelson used to come to bask at the feet of his Delilah. Merton Place,

which he gave to Lady Hamilton after her husband’s death, is close by

the Abbey, and revives the memory of that passionate intrigue, with its

dramatic interplay of glory, shame, and beauty. The drive was not

remarkably picturesque, leading at first through dead-and-alive

provincial streets lined with the various ugliness of the suburban

villa, and then issuing beyond the town to pass through a flat and

sufficiently commonplace landscape. But to American eyes no bit of rural

England can be devoid of interest and charm; the most ordinary objects

seem under a spell to bewitch us back into the dream-world of a previous

existence. An ivied wall, a pebbled brook, a thatched and

lattice-windowed cottage, a single-arched stone bridge, an English

daisy, a field of blood-bright poppies, take on a glamour that is not

their own, but is borrowed from a thousand haunting memories of

Shakespeare and

Wordsworth, of Spenser and

Shelley, of Milton and Keats.

The American sentimental traveler in England could supply curious notes

to the expounders of the doctrine of heredity or the believers in the

transmigration of souls. Was it he, or his remote forefather, who stood

centuries ago precisely under this knotty-limbed oak, amid these crisply

hedged, velvet-swarded meadows, opposite that identical gabled cottage

of stone, smothered in its wealth of black-green ivy? How intimately he

knows it all, how inexpressibly dear to him is the soil beneath his

feet, the ever-changing mist and cloud-veiled sky above his head, the

atmosphere of luxurious repose, the half-tearful, half-smiling, maternal

look in the eyes of Nature, welcoming him to his ancestral home! Thus we

drove through the tame and level fields of North Surrey with that

subdued thrill of perfect physical and emotional content, that "sacred

and home-felt delight," which we had come to associate with the very

grass and air of England. The English friends who accompanied us had

grown used to our easily excited enthusiasm, and appeared themselves to

enjoy the familiar landscape through the medium of our fresher

transatlantic vision. Feeling that we must be nearing our goal, we began

to inquire of the passers-by our way to the Abbey, and before long we

approached a plain, low, double house set back and somewhat raised from

the level of the road, where we saw, framed against the black background

of one of the upper windows, the cordial face and stalwart figure of

William Morris, clad in a dark-blue blouse. Before we had alighted he

was at the gate to receive us, welcoming us with his great, hearty voice

and warm hand-grip. "The idle singer of an empty day" might sit for the

portrait of his own Sigurd. He has the robust, powerful form of a

Berserker, crowned with a tall, massive head, covered with a profusion

of dark, curly hair plentifully mixed with gray. His florid color and a

certain roll in his gait and a habit of swaying to and fro while talking

suggest the sailor or the yeoman, but still more distinctly is the poet

made manifest in the fine modeling and luminous expression of the

features. An indescribable open-air atmosphere of freedom and health

seems to breathe from his whole personality.

arly in July the roses fairly run riot in the garden-like county of

Surrey; all along the railway the little village stations are walled

with thickly flowering vines, or hedged with blooming bushes. From one

of these small, bevined stations in a deep cutting of the Croydon road,

we started — a party of four — on a soft, gray midsummer morning for a

day at Merton Abbey.

Merton Abbey! the very name suggests visions of

venerable Norman arches and cloisters, the roofless aisles and topless

columns of some ruined seat of ecclesiastical power. In point of fact

the Abbey whither we were bound is merely a utilitarian factory that

supplies the marketwares for

Morris & Co.’s decorative art shop in

Oxford street. "'Tis five miles from Croydon, one mile from Wimbledon,"

Mr. Morris had said, in directing us where to find him; and we had

chosen to take the shortest part of the little journey by rail, and to

drive in an open carriage from Croydon to Merton. Here the enamored

Nelson used to come to bask at the feet of his Delilah. Merton Place,

which he gave to Lady Hamilton after her husband’s death, is close by

the Abbey, and revives the memory of that passionate intrigue, with its

dramatic interplay of glory, shame, and beauty. The drive was not

remarkably picturesque, leading at first through dead-and-alive

provincial streets lined with the various ugliness of the suburban

villa, and then issuing beyond the town to pass through a flat and

sufficiently commonplace landscape. But to American eyes no bit of rural

England can be devoid of interest and charm; the most ordinary objects

seem under a spell to bewitch us back into the dream-world of a previous

existence. An ivied wall, a pebbled brook, a thatched and

lattice-windowed cottage, a single-arched stone bridge, an English

daisy, a field of blood-bright poppies, take on a glamour that is not

their own, but is borrowed from a thousand haunting memories of

Shakespeare and

Wordsworth, of Spenser and

Shelley, of Milton and Keats.

The American sentimental traveler in England could supply curious notes

to the expounders of the doctrine of heredity or the believers in the

transmigration of souls. Was it he, or his remote forefather, who stood

centuries ago precisely under this knotty-limbed oak, amid these crisply

hedged, velvet-swarded meadows, opposite that identical gabled cottage

of stone, smothered in its wealth of black-green ivy? How intimately he

knows it all, how inexpressibly dear to him is the soil beneath his

feet, the ever-changing mist and cloud-veiled sky above his head, the

atmosphere of luxurious repose, the half-tearful, half-smiling, maternal

look in the eyes of Nature, welcoming him to his ancestral home! Thus we

drove through the tame and level fields of North Surrey with that

subdued thrill of perfect physical and emotional content, that "sacred

and home-felt delight," which we had come to associate with the very

grass and air of England. The English friends who accompanied us had

grown used to our easily excited enthusiasm, and appeared themselves to

enjoy the familiar landscape through the medium of our fresher

transatlantic vision. Feeling that we must be nearing our goal, we began

to inquire of the passers-by our way to the Abbey, and before long we

approached a plain, low, double house set back and somewhat raised from

the level of the road, where we saw, framed against the black background

of one of the upper windows, the cordial face and stalwart figure of

William Morris, clad in a dark-blue blouse. Before we had alighted he

was at the gate to receive us, welcoming us with his great, hearty voice

and warm hand-grip. "The idle singer of an empty day" might sit for the

portrait of his own Sigurd. He has the robust, powerful form of a

Berserker, crowned with a tall, massive head, covered with a profusion

of dark, curly hair plentifully mixed with gray. His florid color and a

certain roll in his gait and a habit of swaying to and fro while talking

suggest the sailor or the yeoman, but still more distinctly is the poet

made manifest in the fine modeling and luminous expression of the

features. An indescribable open-air atmosphere of freedom and health

seems to breathe from his whole personality.

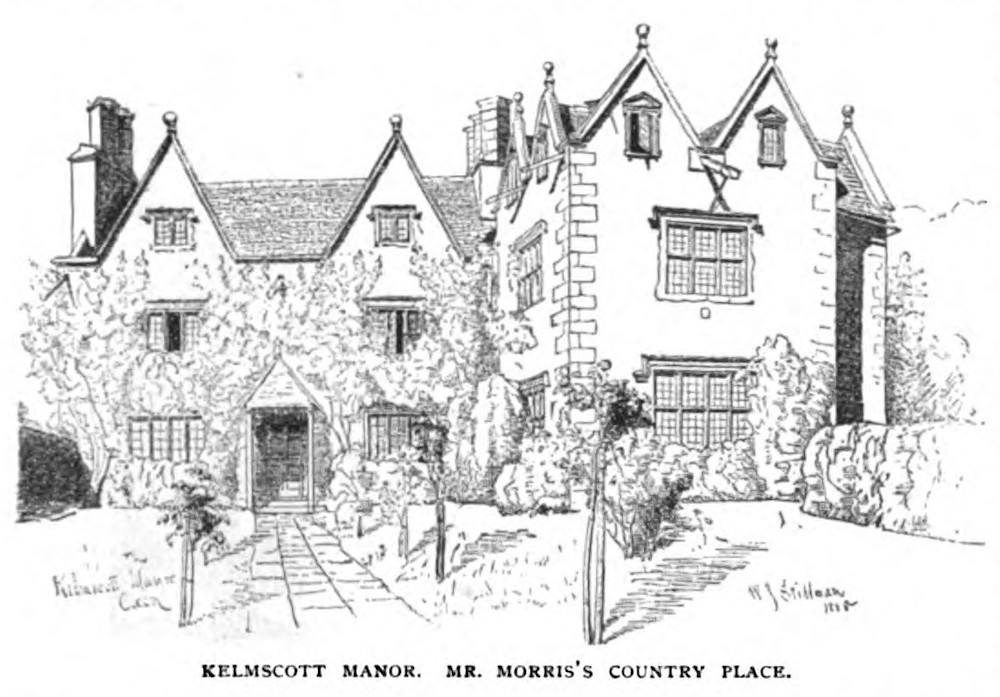

Merton Abbey was originally, as its name implies, a Norman monastery, but since the time of Cromwell it has been adapted to manufacturing purposes, and Mr. Morris, therefore, had no need to run counter to his art-instinct by transforming to business purposes a thing of pure beauty. For that matter, it is scarcely doubtful but that Morris the friend of the workingman would have ruthlessly overridden the compunctions of the author of "The Earthly Paradise," if necessary to give better facilities of air and sunshine to the artisan. The situation of Merton, within ten miles from London, as well as its command [388/389] of water-power, eminently fits it for its present purpose, and the only visible relics of its ancient character are the broken fragments of a wall overgrown with the rank vegetation of ruins. This wall, which surrounded the Abbey lands, bounded a space of sixty acres. Some thirty years ago there still remained a piece of the old buildings, not on Mr. Morris’s ground, but on the adjoining property of Mr. Littler, whose print-works are on the other side of the railway. Unfortunately, however, this interesting relic was allowed to fall into complete decay, and to be finally swept away.

The religious establishment dates back to the beginning of the twelfth century, when Gilbert Norman, sheriff of Surrey, built here a convent for canons of the order of St. Austin upon the demesne granted him by Henry I. Merton Abbey, as it was then called, was patronized by Stephen and Matilda, and was amply endowed with rich gifts. It is closely connected with at least two events of historic importance. A parliament was held within its walls in 1236, when the "Statutes of Merton" were enacted, and when was made the memorable reply of the English nobles to the [389/390] prelates who wished to conform the civil to the ecclesiastical code: "We will not change the laws of England," (Nolumus leges Angliæ mutare). In this house also was concluded the treaty of peace between Henry III and the Dauphin. Upon the breaking up of the monasteries, after the Reformation, it was leased out to private persons, and is said to have been used as a prison during the civil war of Charles I. To-day a branch of the "Democratic Federation" is peacefully and busily installed within its precincts, and in this romantic old garden, haunted by ghosts of sovereigns and monks, of legislators and nobles, of soldiers and artisans, the poet-socialist loves to sit and dream, building a thousand beautiful hopes of freedom and happiness for the people, — on this little spot of soil in which English law and English liberty took such deep and early root.

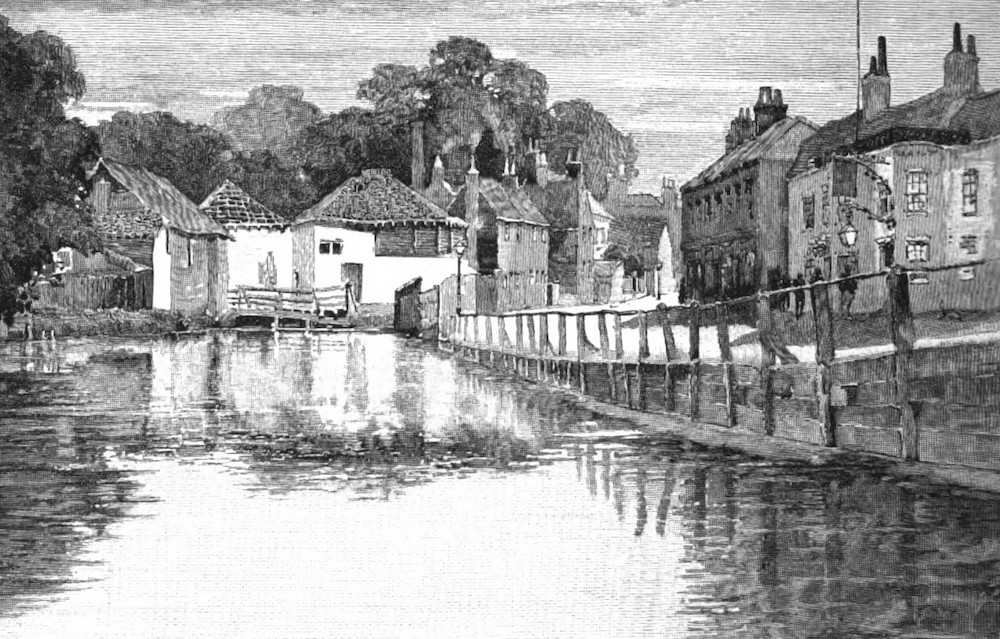

The Town of Merton Abbey.

We were interested to hear that the place is the cradle of textile printing in England. Lysons, writing in 1726, says that two thousand men were employed within the boundaries of the Abbey, and he displays his "characteristic Philistinism" (as Mr. Morris termed it) by taking occasion to contrast this useful labor with the laziness of the old monks. "The block-printing industry still lives, or rather languishes," said Morris, "on the Wandle, but is pretty much confined at present to silk-printing (mostly for the Indian market), and the occupation of the blockers is very precarious." Following the guidance of our host, we found ourselves in an old-fashioned country dwelling-house, almost bare of furniture. In a small room over the stairs was a little circulating library for the benefit of the operatives; the books were as richly bound as though intended for the poet's private shelves, in consonance with his theory that the workingman must be helped and uplifted, not only by supplying his grosser wants, but by developing and feeding his sense of beauty.

The Workshop.

The manufactory consists of a small group of detached buildings where the various processes of dyeing, stamping, and weaving fabrics of wool, cloth, and silk, and of staining designs upon glass, are carried on by male and female operatives of all ages, from fourteen or fifteen upward, and of different degrees of skill, ranging from the uneducated mechanic or dye-mixer to the intelligent artist. In the first outhouse that we entered stood great vats of liquid dye, into which some skeins of unbleached wool were dipped for our amusement; as they were brought dripping forth, they appeared of a sea-green color, but after a few minutes’ exposure to the air, they settled into a fast, dusky blue. Scrupulous neatness and order reigned everywhere in the establishment; pleasant smells as of dried herbs exhaled from clean vegetable dyes, blent with the wholesome odors of grass and flowers and sunny summer warmth that freely circulated through open doors and windows. Nowhere was one conscious of the depressing [390/391] sense of confinement that usually pervades a factory; there was plenty of air and light even in the busiest room, filled with the ceaseless din of whirring looms where the artisans sat bending over the threads; while the lovely play of color and beauty of texture of the fabrics issuing from under their fingers relieved their work of that character of purely mechanical drudgery which is one of the dreariest features of ordinary factory toil. Yet this was evidently the department that entailed the most arduous and sedentary labor, for as we went out again into the peaceful stillness of the July landscape, Mr. Morris reverted with a sigh to the great problem, and asked why men should be imprisoned thus for a lifetime in the midst of such deafening clatter, in order to earn a bare subsistence, while the average professional man pockets in comfortable ease a fee out of all proportion to his exertions? The obvious answer, referring to the relative scarcity of intellectual as compared with physical capacity, seemed to lose much of its pertinence when addressed to a man who had tested both kinds of labor and could so accurately measure their relative claims. There is no branch of work performed in Mr. Morris's factory in which he himself is not skilled; he has rediscovered lost methods and carefully studied existing processes. Not only do his artisans share his profit, but at the same time they feel that he understands their difficulties and requirements, and that he can justly estimate and reward [391/392] their performance. Thus an admirable relation is established between employer and employed, a sort of frank comradeship, marked by mutual respect and good-will. In this relation, Mr. Morris seems to have borrowed all that was sound and admirable from the connection between the medieval master-workman and his artist-apprentices. The excellent custom, restored from the generally despised days that preceded the invention of the steam-engine, Mr. Morris has modified, by adding thereto that spirit of intimate, boundless sympathy which under the name of humanitarianism is the peculiar product, as it is the chief dawning glory, of our own age. The exquisite fabrics to be found in his workshop, which have so largely influenced English taste in household decoration, are intended to perform another service less conspicuous but still more important than the first. That the workman shall take pleasure in his work, that decent conditions of light and breathing-space and cleanliness shall surround him, that he shall be made to feel himself not the brainless "hand," but the intelligent coöperator, the friend of the man who directs his labor, that his honest toil shall inevitably win fair and comfortable wages. whatever be the low-water record of the market-price of men, that illness or trouble befalling him during the term of his employment shall not mean dismissal and starvation,— these are some of the problems of which Mr. Morris's factory is a noble and successful solution. For himself, he eschews wealth and luxury, which are within easy reach of his versatile and brilliant talents, in order that for a few at least of his brother men he may rob toil of its drudgery, servitude of its sting, and poverty of its horrors.

Mr. Morris’s work has two distinct moral purposes,— one in its bearing upon the producer, which we have just considered, and the other in its relation to the purchaser. In the latter connection his aim has been to revive a sense of beauty in home life, to restore the dignity of art to ordinary household decoration. So strong and wide has been his influence that he may be said to have revolutionized English taste in decorative art. Graceful designs reproduced from natural outdoor objects, fabrics of substantial worth, be they the simplest cotton stuffs or the most exquisite silks and brocades, colors that shall stay fast through sunshine and shade,— these are the general characteristics of his manufactures. By a singular fatality, his very success has been in certain ways detrimental to him. His [392/393] designs have been imitated by manufacturers less scrupulous as to quality and thoroughness, until their peculiar charm or individuality is almost lost sight of. They have been cheapened and commonplaced, and so distorted from their original purpose as apparently to encourage indirectly that very taste for useless luxuries, sham art, and stupid bric-à-brac which it has been his chief endeavor to destroy. His name has become for some people (more especially in America) falsely associated with that modern fashion which is his detestation, of encumbering our rooms with silly baubles that, in his own words, "make our stuffy, art-stifling houses more truly savage than a Zulu’s kraal or an East Greenlander's snow-hut." He has a special proclivity for "frank colors," pure and solid, and yet, as he himself complains with whimsical despair, "he is supposed to have brought into vogue a dingy, bilious-looking yellow-green — a color of which he has a special and personal hatred." All this misunderstanding arises not from any lack of clearness or consistency in his expression, but simply because of the perversion of his ideas through copies, imitation, and misreport, and the unwillingness of many people to dispel their hazy notion of him by examining for themselves his actual work, whether in literature or in decorative art. No one insists more strenuously than he upon the necessity of simplifying our lives. "Nothing can be a work of art which is not useful, that is to say, which does not minister to the body when well under command of the mind, or which does not amuse, soothe, or elevate the mind in a healthy state. What tons upon tons of unutterable rubbish, pretending to be works of [393/394] art in some degree, would this maxim clear out of our London houses if it were understood and acted upon." For "London" read New York, and the lesson comes home to us with tenfold force. "If you cannot learn to love real art, at least learn to hate sham art and reject it. Learn to do without — there is virtue in those words, a force that rightly used, would choke both demand and supply of mechanical toil . . . And then from simplicity of life would rise up the longing for beauty; and we know that nothing can satisfy that demand but intelligent work, rising gradually into imaginative work, which will turn all operators into workmen, into artists, into men."

The Mill-Pond.

In accordance with these ideas, one is not surprised to find his factory a scene of cheerful, uncramped industry, where toil looks like pleasure, where flowers are blooming in the windows, and sunshine and fresh air brighten the faces of artist and mechanic. After going through all the workshops, the best part of our visit has yet to come, in a walk through the enchanting old garden.

A fair, green close,

Hedged round about with woodbine and red rose.

…And all about were dotted leafy trees,—

The elm for shade, the linden for the bees;

The noble oak long ready for the steel,

That in that place it had no fear to feel.

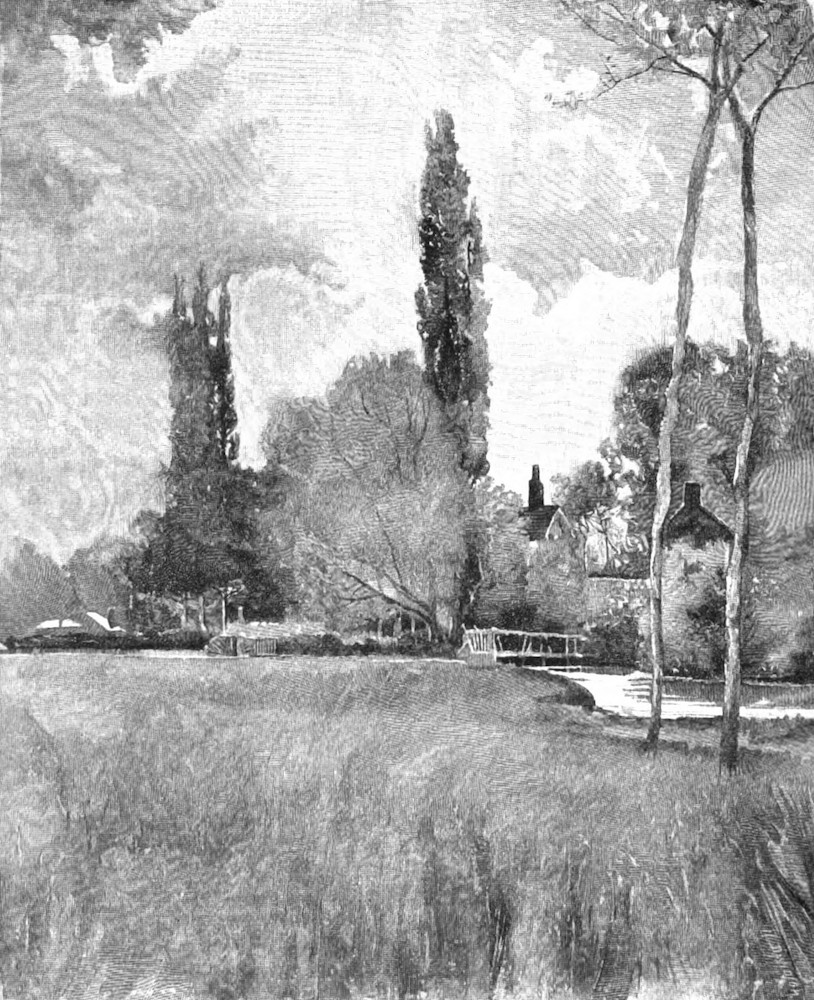

Are there just such gardens anywhere out of England, with their careless profusion and variety, their delightful little accidental walks and lanes leading nowhither, their absence of all primness in the arrangement of flower and berry beds, of all formality in their freely expanding, generously blooming trees! Here we stood for some time beside the merry little Wandle, which is no less full of sparkle and music because it has been coaxed into turning the great mill-wheel below the dam. Growing thick along the water, the blue-gray willows etch their delicate tracing of boughs against the soft sky.

Over the leaves of the garden blooms the many folded rose

If the Surrey roses were rich and plentiful along railway and roadside, what shall be said of their abundance and splendor in this protected spot! They clambered along the ruined abbey wall, and started up from bush and vine on every side, making the air spicy with their sweetness. Under the direction of this poet-husbandman, even the orchard and kitchen-garden seemed to wear a certain spontaneous grace with the partly disguised regularity of their well-ordered rows. Here, besides ordinary edible roots and pants, flourish others which were not considered susceptible of cultivation in England until Mr. Morris introduced them in order to extract particular juices for his dyes. One of the clear, brilliant yellows frequently employed in his fabrics is procured from the bushes of his garden. At our feet ripe strawberries nestled under their dark leaves, and overhead tall, gently rustling trees screened us from the tempered heat of the English sun. All was freshness and grace, all spoke of loving sympathy with nature and intelligent command of her virtues and activities; all was impregnated with that free, large, and wholesome beauty which Mr. Morris seems to obtain from everything that surrounds him.

In making the personal acquaintance of one whose artistic work is familiar and admirable to us, the main interest must ever be to trace the subtle, elusive connection between the man and his creation. In the case of Mr. Morris. At first sight, nothing can be more contradictory than the “dreamer of dreams born out of his due time,” and the practical business man and eager student of social questions who successfully directs the Surrey factory and the London shop. Little insight is required, however, soon to find beneath this thoroughly healthy exterior the most impersonal and objective English poet of our generation. The conspicuous feature of his conversation and character is the total absence of egoism, and we search in vain through his voluminous writings for that morbid habit of introspection which gives the keynote to nineteenth-century literature. He has the childlike delight in telling a story for the story’s sake of Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Scott, the plastic power of setting before us in simple and distinct outlines figures of force and grace entirely removed from his own conditions and temperament, the unmoralizing, hearty pleasure in nature and art which characterized an earlier age. He has succeeded in forgetting, and in making us

Forget six counties overhung with smoke,

Forget the snorting steam and piston-stroke,

Forget the spreading of the hideous town,

and in setting before us

A nameless city in a distant sea,

White as the changing walls of faërie.

The passion for beauty, which unless balanced by a sound and earnest intelligence is apt to degenerate into sickly and selfish æsceticism, inflames him with the burning desire to bring all classes of humanity under its benign influence. That art, together with the leisure and capacity to enjoy it, should be monopolized by the few, seems to him as [394/395] egregious a wrong as that men should go hungry and naked. With this plain clew to the poet’s character, there is no longer any contradiction between the uncompromising socialist and the exquisite artist of "The Earthly Paradise." If Mr. Morris's poetry have (as I think no one will dispute) that virginal quality of springtide freshness and directness which we generally miss in modern literature, and which belonged to Chaucer as to Homer, the cause may be found in his reproduction in methods and principles of life of certain conditions under which classic art was generated. He has chosen to be a man before being a poet; he has rounded and developed all sides of a well-equipped and powerful individuality; he has plunged vehemently into the rushing stream of current action and thought, and has made himself at one with his struggling, panting, less vigorous fellow-swimmers. He has not only trained himself intellectually to embrace with wide culture the spirit of Greek mythology, the genius of Scandinavian as of Latin poetry, but he has cultivated muscle and heart as well as nerve and brain. The result upon his art has been indirect, but none the less positive. He seems intuitively to have obeyed those singular rules for poetic creation formulated by Walt Whitman:

Who troubles himself about his ornaments or fluency is lost. This is what you shall do: love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence towards the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown, or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful, uneducated persons, and with the young and with the mothers of families, . . . reëxamine all you have been told at school or at church, dismiss whatever insults your soul,— and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency, not only in its words, but in the silent lines of your lips and face, and between the lashes of your eyes, and in every motion and joint of your body.

Mr. Morris’s extreme socialistic convictions are the subject of so much criticism at home, that a few words concerning them may not be amiss here. Rather would he see the whole framework of society shattered than a continuance of the actual condition of the poor. "I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few or freedom for a few. No, rather than that art should live this poor, thin life among a few exceptional men, despising those beneath them for an ignorance for which they themselves are responsible, for a brutality which they will not struggle with; rather than this, I would that the world should indeed sweep away all art for a while [...] Rather than the wheat should rot in the miser's granary, I would that the earth had it, that it might yet have a chance to quicken in the dark."

The River.

The above paragraph, from a lecture delivered by Mr. Morris before the Trades' Guild of Learning, gives the key to his socialistic creed, which he now makes it the main business of his life to promulgate. In America the avenues to ease and competency are so broad and numerous, the need for higher culture, finer taste, more solidly constructed social bases is so much more conspicuous than the inequality of conditions, and the necessity to level and destroy, that the intelligent American is apt to shrink with aversion and mistrust from the communistic enthusiast. In England, however, the inequalities are necessarily more glaring, the pressure of that densely crowded population upon the means of subsistence is so strenuous and painful, that the humane on-looker, whatever be his own condition, is liable to be carried away by excess of sympathy. One hears to-day of individual Englishmen of every rank flinging themselves with reckless heroism into the breach, sacrificing all thought of personal interest in the desperate endeavor to stem the huge flood of misery and pauperism. Among such men stands William Morris, and however wild and visionary his hopes and aspirations for the people may appear to outsiders, his magnanimity must command respect. No thwarted ambitions, no stunted capacities, no narrow, sordid aims have ranged him on the side of the disaffected, the agitator, the [395/396] outcast. As poet, scholar, householder, and capitalist, he has everything to lose by the victory of that cause to which he has subordinated his whole life and genius. The fight is fierce and bitter; so thoroughly has it absorbed his energies, so filled and inspired and illumined is he with his aim, that it is only after leaving his presence we realize that it is to this man's strong and delicate genius we owe the enchanting visions of The Earthly Paradise, and Sigurd the Volsung, the story of Jason, and, The Aeneids of Virgil. * —Emma Lazarus

* The following extract from a letter addressed to me by Mr. Morris, bearing date of April 21, 1884, will help to elucidate his socialistic and artistic views. —E.L.:

"I have no objection to stating the kind of profit-sharing that goes on in my business; it would not be worth while to give details of it. The profit-sharing only extends at present to the managers and heads of departments, not to use a grand word, foremen if you please, although properly speaking we have no foremen. The greater part of our men are paid by piecework, according to the custom of their trade; this makes it neither so necessary that they should share profits, nor so easy to arrange a scheme. And now I must state that when I began to turn my attention to this matter of profit-sharing, though I had little faith in its proving a solution of the labor and capital question, I thought it might advance that solution somewhat in the absence of any distinct attempt towards universal coöperation, i.e., socialism, and I hope to [396/397] be able to put my whole establishment on a profit-sharing basis. I now see clearer why I had no faith in the profit-sharing, and at the same time see that things are tending towards socialism, so that there is no temptation to me to try to advance a movement which in its incompleteness would rather injure than help the cause of labor. At the same time, I see no harm in the profit-sharing business within certain limits; if, I mean to say, it only means raising the wages at the expense of the individual capitalist. I have always done this by giving wages above the ordinary market-price, and always shall do so.

"I ought to say why I think mere profit-sharing would be no solution of the labor difficulty. In the first place, it would do nothing towards the extinction of competition, which lies at the root of the evils of to-day; because each coöperative society would compete for its corporate advantage with other societies, would in fact so far be nothing but a joint-stock company. In the second place, it would do nothing towards the extinction of exploitage, because the most it could do in that direction would be to create a body of small capitalists, who would exploit the labor of those underneath them quite as implacably as the bigger capitalists do; just as peasant proprietors do in the matter of rent for land. In the third place, the immediate result of the system of profit-sharing would be an increase of overwork amongst the industrious, who would, of course, always tend upward toward that small capitalist class abovesaid. This would practically mean putting the screw on all wage-earners and intensifying the contrast between the well-to-do and the mere unskilled, the hewers of wood and drawers of water; for all these industrious successful people would take good care to have people to live on lower down. General result, increase of work done, which all reasonable people should try to curtail, increase of luxury, increase of poverty. Thus, you see, so accursed is the capitalist system under which we live, that even what should be the virtues of good management and thrift, under its slavery do but add to the misery of our thralldom and indeed become mere vices, and have at last the faces of cruelty and shabbiness. The bourgeois system is doomed, that is the long and short of it, and this permissible coöperative system, with its apparent fairness of sharing of profits, is but an attempt at insurance for it, by the creation of a fresh set of petty bourgeois.

“So much for sociology; a word or two about the art I have tried to forward. That is a simple matter enough. I have tried to produce goods which should be genuine as far as their mere substances are concerned, and should have on that account the primary beauty in them which belongs to naturally treated natural substances; have tried, for instance, to make woolen substances as woolen as possible, cotton as cottony as possible, and so on; have used only the dyes which are natural and simple, because they produce beauty almost without the intervention of art; all this quite apart from the design in the stuffs or what not. On that head it has been, chiefly because of the social difficulties, almost impossible to do more than to insure the designer (mostly myself) some pleasure in his art by getting him to understand the qualities of materials and the happy chances of processes. Except with a small part of the more artistic side of the work, I could not do anything (or at least but little) to give this pleasure to the workmen, because I should have had to change their method of work so utterly that I should have disqualified them from earning their living elsewhere. You see I have got to understand thoroughly the manner of work under which the art of the Middle Ages was done, and that that is the only manner of work which can turn out popular art, only to discover that it is impossible to work in that manner in this profit-grinding society. So on all sides I am driven towards revolution as the only hope, and am growing clearer and clearer on the speedy advent of it in a very obvious form, though of course I can’t give a date for it . . .. I am, etc.,

“Yours very truly, WILLIAM MORRIS.”

Links to Related Material

- William Morris -- Artistic Relations

- Morris and Co.

- Wandle (textile designed by Morris)

Bibliography

Lazarus, Emma. "A Day in Surrey with William Morris." The Century Magazine (July 1886): pp. 388-397.

Created 31 July 2024 Last modified 10 August 2024