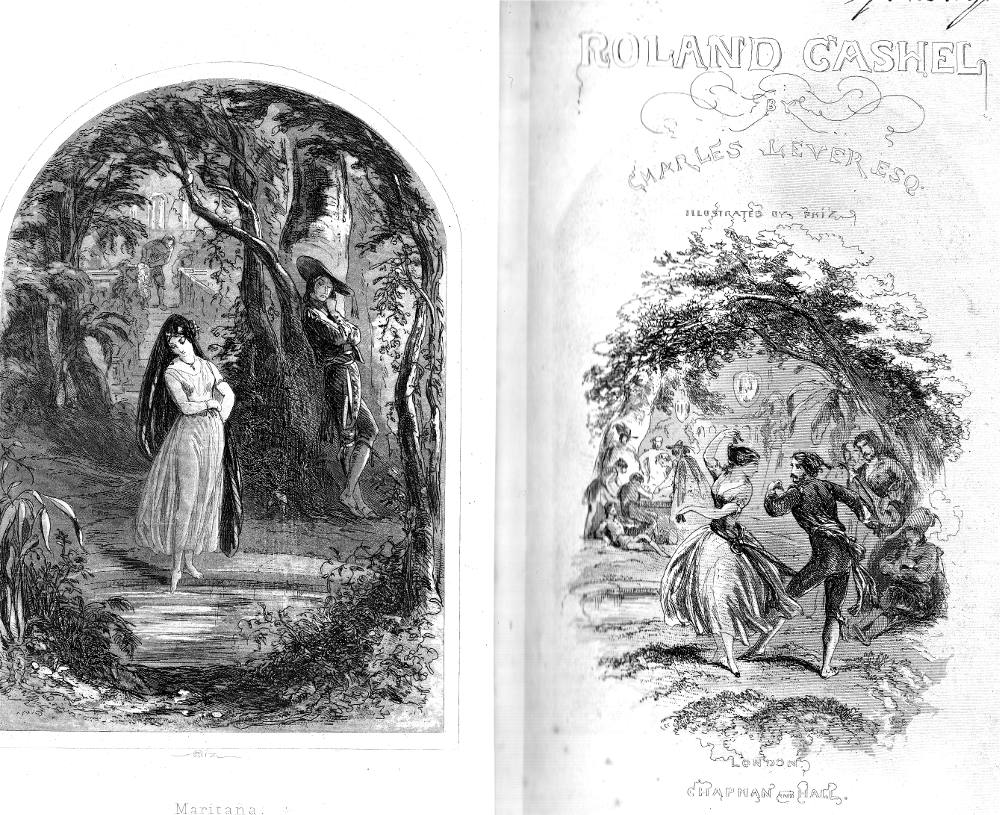

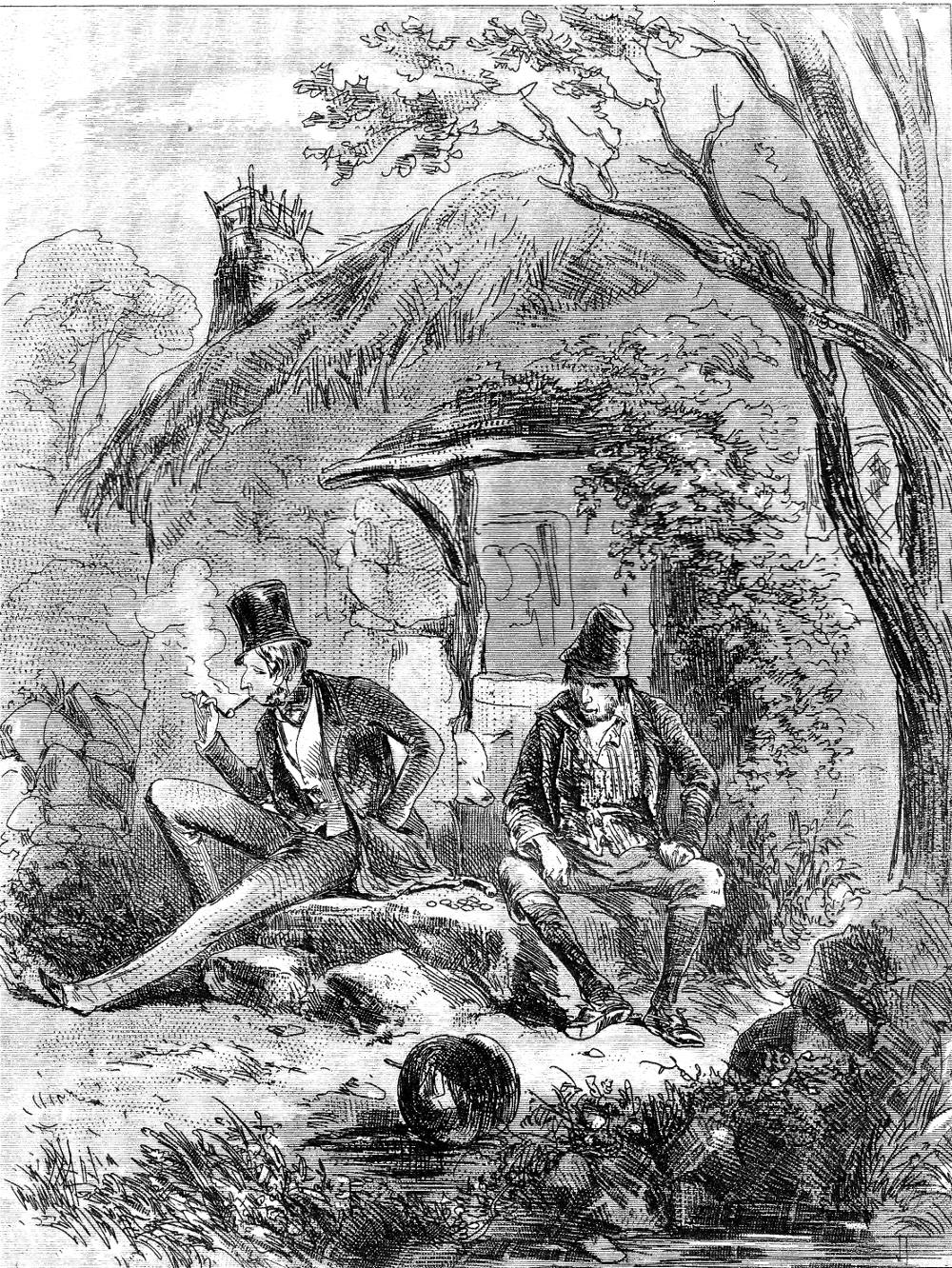

Published by Chapman and Hall in two volumes in 1850, Roland Cashel is a work belonging to Charles Lever's mature period. Unlike his first four military picaresque/Bildungsroman novels of the 1840s, Roland Cashel deals in a sober albeit exciting manner with Protestant-Catholic tensions in Ireland, tackling such awkward issues as the effects of absentee landlords and the corrosive potential of Irish nationalism in the early 1830s. And, although Lever's illustrator is once again Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne), the style of the monthly engravings is realistic rather than caricatural, compelling readers to reflect upon key characters, their motivations, and the principal incidents in each number, May 1848 through November 1849.

The novel is a direct result of the Irish factionalism that in 1845 had forced Dr. Charles Lever to quit Dublin forever, and live the remainder of his days on the Continent, chiefly in Italy. Like St. Patrick's Eve (1845), Roland Cashel juxtaposes the wealth and political privilege of the landed aristocracy and their professional urban agents with the squalor, poverty, ignorance, and slow-starvation of small farmers in rural districts. In this portrait of social decrepitude Lever thus anticipates of the Irish Famine of the mid-1840s. The most interesting aspect of the 1850 novel is the anguished, self-doubting, conflicted but honourable young protagonist who is a veteran of the Columbian navy and speaks fluent Spanish. Through the serialisation of this socially relevant story Lever hoped to rival Dickens's Dombey and Son while achieving great monthly sales; in this latter quest he was not entirely successful, despite the innovation of opening the narrative in South America.

"In a lovely little villa on the border of the lake [Lago di Como], with that glorious blending of Alpine scenery and garden-like luxuriance around me, and little or none of interruption and intercourse, I had the abundant time to make acquaintances with my characters, and follow them into innumerable situations and through adventures far more extraordinary and exciting than I dared afterwards to recount. The personages of the novel gain over me at times a degree of interest very little inferior to that inspired by living and real people, and this is especially the case when I have found myself in some secluded spot and seeing little of the world.

"When I began I intended that the action should be carried on in the land where the story opened. . . . . When only two or three chapters of Roland Cashel had been drafted, however, the visit to the enchanted lake came to an end. [Stevenson, 167-168]

Re-established in the Palazzo Standish in Florence, Lever re-immersed himself in the social and political life of the venerable city. Among the rich and power foreign company Lever continued to work on the novel, placing his alien protagonist in the midst of the wealthy and fashionable Anglo-Irish of Dublin. Quickly his his new lifestyle consumed his advances on the new novel. Despite the financial pressures, he rose to the challenge of both defending and critiquing Irish national in the new novel Chapman and Hall novel to be issued in monthly parts.

During the period of gestation for Roland Cashel, Charles Lever had transferred his family from a luxurious villa on the shores of Lake Como, playground of a fabulously rich international community, to the Casa Standish in Florence, which he styled the "Palazzo Standish." Owing to copyright problems with his former publisher, the now-bankrupt William Curry of Dublin, Lever continued to live beyond his means. The only thing that kept him afloat financially was the regular advances from Chapman and Hall on the new novel, which he had begun at the Villa Cima in Como. He had little hope of recuperating any profits from stupendous American sales because of cheap transAtlantic piracies, and could only hope that Chapman and Hall could negotiate control of the original copyrights from Curry. No sooner had the colourful Lever party settled in Florence than revolutions broke out: "Florence is the only tranquil spot in Europe," he wrote to a correspondent.

By this time, Roland Cashel was being published by Chapman & Hall in the customary monthly parts. Lever's anxieties prevented him from having much enthusiasm for it: "It is very hard, under such circumstances, to write anything imaginative — the stern cry of reality drowning the small whispering of fancy." Nevertheless, the novel is among his best, and his divagation from his original plan did not prevent it from being soundly and coherently constructed, The shift of scene from Columbia to Ireland gave scope for striking contrasts in the experience of the hero, abruptly transformed from a buccaneering adventurer into a millionaire, and the sequels of his first exploits were skilfully woven into the plot. The only flaw in the story is the constant intermingling of two unassimilable literary genres — grim melodrama and mordant social satire. The melodramatic plot builds up to a climax of murder with many of the neat devices of a modern detective story, and has an Iago-like villain who is strangely convincing — indeed Lever protested that "I made but a faint copy of him who suggested that personage, and who lives and walks the stage of life as I write (in 1871). One or two persons who know him are aware that I have neither overdrawn my sketch nor exaggerated my drawing." [Stevenson, 173]

Nevertheless, the novel is among his best, and his divagation from his original plan did not prevent it from being soundly and coherently constructed. The shift of scene from Columbia to Ireland gave scope for striking contrasts in the experience of the hero, abruptly transformed from a buccaneering adventurer into a millionaire, and the sequels of his first exploits were skilfully woven into the plot. The only flaw in the story is the constant intermingling of two unassimilable literary genres — grim melodrama and mordant social satire. [Stevenson, 173-174]

In the satire on Dublin society, he paid off many grudges. "The whole dramatis personae are portraits," he gleefully old Spencer. [Stevenson, 174]

The Twenty Serial Instalments of Roland Cashel (1848-49)

- 1 May 1848 Chapters I-VI.

- 2. June 1848 Chapters VII-IX.

- 3. July 1848 Chapters X-XII.

- 4. August 1848 Chapters XIII-XIV.

- 5. September 1848 Chapters XV-XVII.

- 6. October 1848 Chapters XVIII-XIX.

- 7. November 1848 Chapters XX-XXI.

- 8. December 1848 Chapters XXII-XXV.

- 9. January 1849 Chapters XXVI-XXIX.

- 10. February 1849 Chapters XXX-XXXII.

- 11. March 1849 Chapters XXXIII-XXXVI.

- 12. April 1849 Chapters XXXVII-XXXIX.

- 13. May 1849 Chapters XL-XLI.

- 14. June 1849 Chapters XLII-XLVI.

- 15. July 1849 Chapters LII-LIII.

- 16. August 1849 Chapters LIV-LIX.

- 17. September 1849 Chapters LX-LXIII.

- 18. October 1849 Chapters LXIV-LXVII.

- 19/20. November 1849 Chapters LXVIII-LXXII.

Geographical and Socio-political Associations: Victorian Ireland

- The Landscape of Ireland

- The Geography of Ireland

- Ireland in The Illustrated London News

- Victorian Ireland

- The Land War in Ireland

- The Irish Famine: 1845-49

Bibliography

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

Lester, Valerie Browne Lester. Chapter 11: "'Give Me Back the Freshness of the Morning!'" Phiz! The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 108-127.

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. London: Chapman and Hall, 1850.

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Vols. I and II. In two volumes. London: Routledge, 1877, Rpt. Boston: Little, Brown, 1907. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: 19 August 2010.

Steig, Michael. Chapter Seven: "Phiz the Illustrator: An Overview and a Summing Up." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 298-316.

Stevenson, Lionel. Chapter X, "Onlooker in Florence, 1847-1850." Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. London: Chapman and Hall, 1939. Pp. 165-183.

_______. "The Domestic Scene." The English Novel: A Panorama. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin and Riverside, 1960.

Created 17 February 2023