Kot Dafadar Major. 5th Bombay Cavalry by A. N. Bowling. 1897. Courtesy of the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University. Click on this image and those following to enlarge them.

John Keats and Napoleon had both died in 1821, events noted, but probably not grieved over by Jerdan. However, 1822 started very sadly for him. He received news of the death of his beloved elder brother John Stuart who had distinguished himself in Kutch, at a cost to his health. Then a Colonel in the 5th Bombay Regiment, he was invalided, and on his way home from India when his ship stopped at the Cape of Good Hope. He succumbed to illness and died on 8 January, aged 54. Jerdan allowed himself the indulgence of writing proudly about his brother in his Autobiography, sketching his military achievements, noting tributes paid to him as “a gallant officer and a most estimable man” (3.236; 1.16, 226). In addition to describing his courage and admirable qualities as an officer, Jerdan dwelt lovingly on his personal tie with his older brother and, in doing so, revealed himself to be well aware of his own faults and frailties:

His letters to me were of infinite interest, and gave the most vivid accounts of Indian warfare and the manners of the people that ever I read; and yet a stronger proof of his superior intellect was afforded in those parts of his correspondence which were of a private nature. His fraternal advice to me, founded on an exact appreciation of my character, and those foibles or weak points which he thought were calculated to affect my progress in life, showed wonderful discernment, and could hardly be explained with reference to the distance between us and the few opportunities he had of studying that which he certainly understood so well. I used to be surprised by his acumen; and it might have been better for me had I been as sensibly instructed by his wisdom as I was impressed by his fraternal earnestness and astute talent.

The personal loss of such a man was severe indeed, but Jerdan may have been slightly soothed by a letter from George Canning, the postscript of which offered condolences for his bereavement.

The main part of Canning’s letter however, declined Jerdan’s invitation to preside over the Literary Fund Anniversary Dinner in the Spring. Embarrassed, Canning asked to be excused on this occasion, having refused innumerable similar requests, as “it destroys the roundess of my assertion that I do not frequent such meetings” (4.44). Castlereagh had recently committed suicide, and Canning succeeded him as Foreign Secretary and Tory Leader in the Commons, high offices which made him even more cautious than was his nature. In March Jerdan was elected to the General Committee of the Literary Fund, and continued to enjoy the Anniversary Dinners for many years. As well as being jolly social occasions, they were vital to keep the Fund growing. At this time Croly reported that in the preceding seven years the Literary Fund had aided 239 cases, dispensing the sum of £2294.

Mourning his beloved brother, Jerdan had other things to cheer him, at this time. The publication of Landon’s Poetic Sketches at the beginning of the year marked the appearance of her poetry in almost every issue of the Literary Gazette for that year. Eventually there was a series of six Poetic Sketches, comprising twenty-eight poems in all, appearing irregularly until 1825. Many of the poems described paintings and contemporary engravings, others came from Landon’s imagination. The overall impression was one of repressed emotions, the cruelty of absent lovers, and hopeless passion – the antithesis to what was really happening in her life, another example of the “mask” she hid behind.

In the absence of new evidence coming to light, it can safely be assumed that all of Landon’s poetic output at this time was written with Jerdan in mind, and addressed to him directly (Lawford). Knowing this, the “Poetic Sketches” take on an even more wild and daring aspect: “Call to mind/The arms, the sighs you leave behind.” “Breathe not other sighs, love,” suggest a sexual closeness to a lover, a closeness that to her readers was unthinkable for an unmarried young woman. If they could have had any clue or suspicion as to the truth, then both Landon and Jerdan were taking considerable risks. Her poetry was also targetting a wider audience than Jerdan: “The erotic hold that Landon may have had on Jerdan was translated into a more culturally acceptable reading in her general public” (Rappaport)

For the Literary Gazette the Poetic Sketches were invaluable, becoming L.E.L.’s ‘trademark’. On the publication in the Gazette of 9 February of a eulogy “To L.E.L., on his or her Poetic Sketches in the Literary Gazette” by the poet, Bernard Barton, Jerdan appended a footnote: “We have pleasure in saying that the sweet poems under this signature are by a lady, yet in her teens! The admiration with which they have been so generally read, could not delight their fair author more than it has those who in the Literary Gazette cherished her infant genius. – Ed.” Thus the mystery of the gender of L.E.L. was revealed. Claiming she was in “her teens” was clever of Jerdan, who knew perfectly well that within six months she would be twenty, but “teens” made her sound even younger, adding to her charm and interest. Even her new signature was a stroke of genius: “The three letters very speedily became a signature of magical interest and curiosity…Not only was the whole tribe of initialists throughout the land eclipsed, but the initials became a name” (Blanchard 1.30-31). Her works were eagerly awaited. Edward Bulwer-Lytton described the scene when he was an undergraduate at Cambridge:

There was always, in the Reading Room of the Union, a rush every Saturday afternoon for “The Literary Gazette”, and an impatient anxiety to hasten at once to the corner of the sheet which contained the three magical letters of “L.E.L.” And all of us praised the verse, and all of us guessed at the author. We soon learned it was a female, and our admiration was doubled, and our conjectures tripled. Was she young? Was she pretty? And – for there were some embryo fortune-hunters among us – was she rich?

Landon was writing prolifically, and Jerdan made room in the Literary Gazette for much of her output. The heat of their joint literary enterprise translated into a consummation of the sexual attraction engendered by the close association. At some point in 1822 their affair started in earnest. In his “Memoir of L.E.L.”, Jerdan highlighted 1822 as the year when “L.E.L. was as full of song as the nightingale in May; and excited a very general enthusiasm by the Sapphic warmth, the mournful emotion, and the imaginative invention, the profound thought and the poetic charm with which she invested every strain.” It was clearly a year imprinted on his memory, for the extraordinary situation in which he found himself – lover of a protégée whose poems were the toast of the town, part owner and editor of a respected and profitable journal, and established family man. Life was indeed good.

The speed with which Landon produced poems was astonishing. Her friend Sarah Sheppard remarked on her “graceful quickness in every movement; so accordant with that rapidity of thought which is the especial attribute of genius …Everything seemed accomplished by her without effort. Her thoughts appeared to spring up spontaneously on any proposed subject; so that her literary tasks were completed with a facility and quickness” (Lawford 262). Jerdan already knew that she composed quickly – he had seen it for himself in her poem on St George’s Hospital. He knew that because of the speed of her composition errors and flaws were inevitable, but he allowed these to pass into print unchanged, except for punctuation, which was never Landon’s strong point. Maybe he felt that sometimes she should take a little longer, and more care, but that would have gone against her very nature, the nature of impulse, wildness and passionate emotions, of love and melancholy, which produced the rising success of the magazine, and the excitement of his own secret liaison with her.

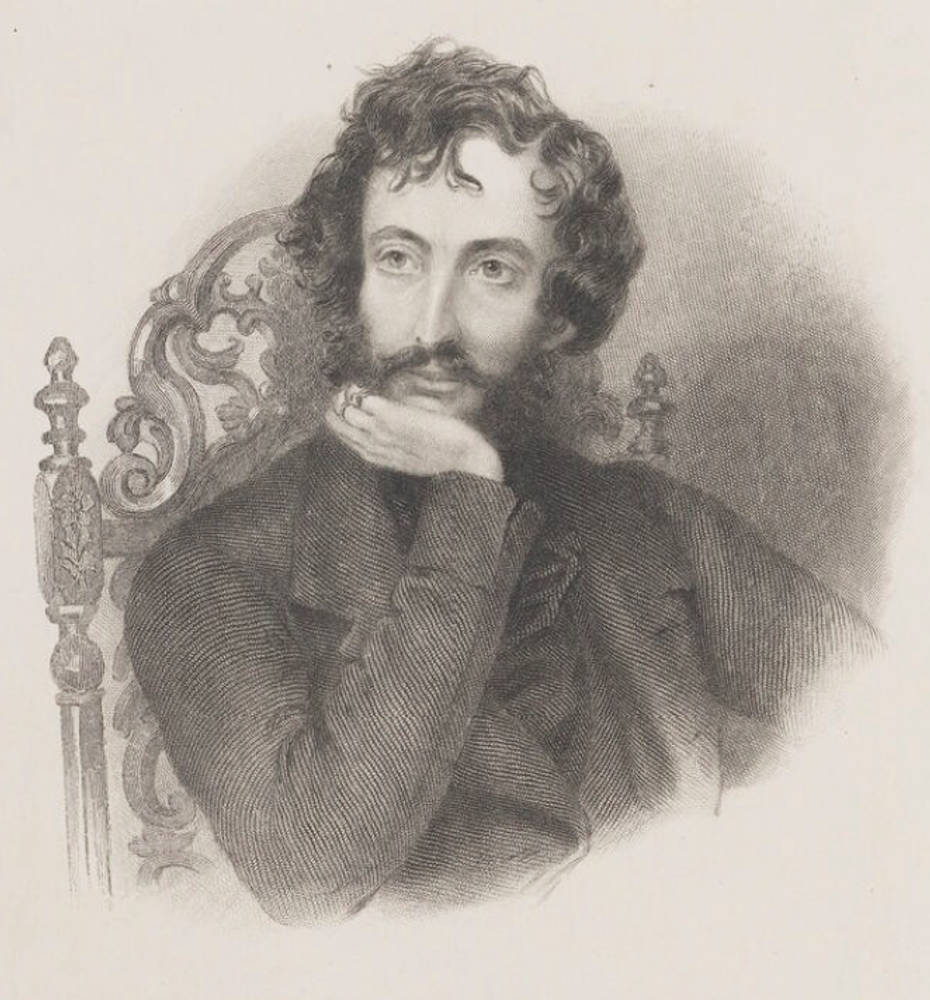

George Gordon Lord Byron. Engraved by H. Robinson after a painting by Richard Westall, R.A.

From the 1840 Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrapbook edited by L.E.L. and Mary Howitt.

Jerdan’s attention to Letitia Landon had to be diverted to other aspects of his responsibilities as editor. At this time a literary quarrel erupted. Byron’s “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers” (text) called Southey a “Ballad-monger” and rhymed his name with “quaint and mouthey”, ridiculing his works (Jerdan, Men I have Known, 408). Southey published a paean to George III in 1821 entitled The Vision of Judgment, in the Preface to which he criticised Byron’s verse, attacked Shelley’s poetry and Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein. The Literary Gazette reviewed Southey’s work harshly, doubly surprising as Southey was a Tory and Poet Laureate, and that the Vision was published by Jerdan’s partners, the Longmans. “…we have no words to describe the mixture of pity and contempt and disapprobation with which the perusal of this piece has filled us”, complained the Literary Gazette. Jerdan’s devastating review was to come back to haunt him later, when Southey took up the cudgels for Charles Lamb against the Literary Gazette (19 January 1822, 41).

A year after the publication of The Vision of Judgment Byron attacked Southey in a poem of his own, using almost the same title, publishing it in the first issue of Leigh Hunt’s journal, the Liberal. This attack served to titillate public interest and this issue of the Liberal made the author a profit of £377.16s, of which he personally pocketed £291.15s (Holden 176). Byron and Hunt were vilified by all who hated the “Cockney School”. In a four page article in the Literary Gazette of 19 January 1822, entitled “Southey and Byron!”, the writer, almost certainly Jerdan, remarked that Southey’s offence was “a common and venial crime when compared with the enormous guilt of his opponent, who links himself in the closest bonds with that abhorrence of humanity, the avowed Atheist, and devotes his brilliant talents, with fiend-like energy, to subvert all that is valuable in social life or blessed in future hope” (41). Towards the end of the year, in an article celebrating the winding up of Hunt’s short-lived Liberal, the Literary Gazette of 19 January 1822 noted that Byron had contributed “impiety, vulgarity, inhumanity…Mr Shelley a burlesque upon Goethe; and Mr Leigh Hunt conceit, trumpery, ignorance and wretched verses. The union of wickedness, folly and imbecility is perfect” (41). There is an irony in the Literary Gazette’s support of this disparagement of Byron’s style, as within the following year or two, L.E.L. became known as “the female Byron”.

Byron’s name was to bedevil Jerdan in numerous ways. This attack was the second time Jerdan had crossed swords with him (almost literally), the first being the occasion when he had made what Byron considered disrespectful remarks on his lines on Mrs Charlemont, “Born in the garret, in the kitchen bred” in A Sketch from Private Life, and had told Jerdan’s travelling companion from Paris, Douglas Kinnaird, to challenge Jerdan to a duel, which never occurred. However, Jerdan never attacked Byron in a personal way; his quarrel was with the immorality he perceived in Byron’s work. This was in accordance with the view he promulgated later: “In legitimate criticism the main and proper business of the reviewer is with the writings before him; and unless the writer dogmatically parades himself, or inculcates dangerous doctrines, there is not a syllable out of the work, either about him or his history which are within the sphere of justifiable remark” (2.3).

If, as the saying goes, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Jerdan must have been in a rosy haze of self-congratulation in the early days of the Literary Gazette’s success. It has been argued that as the Literary Gazette was the first periodical of its kind, any that followed had only the Gazette as their model, that it had begun “a new species”, an achievement that can be credited in large part to Jerdan’s efforts (Pyle 134).

Imitations abounded: The Literary Journal in 1818, which lasted a year and collapsed; the Literary Chronicle, which closely followed the content of the Literary Gazette had better success, commencing in May 1819, producing 471 issues until it merged with the Athenaeum in 1828; and the Somerset House Gazette based on the Literary Gazette, but focussed primarily on painting. This last short-lived publication was edited by W. H. Pyne, well known to Literary Gazette readers for his essay series ‘Wine & Walnuts’. There were others too, that came and went, having little impact on the success of the Literary Gazette. In his Autobiography Jerdan recalled some of these attempts at imitation quite charitably, saying that “the majority were conducted with commendable talent and in a gentlemanly spirit of competition towards their model, notwithstanding that its pre-occupancy of the public kept them in the background” (3.210). The Literary Gazette was well known in America as early as 1821, when a similarly named journal appeared in Philadelphia, announcing that it would “be conducted very nearly upon the plan of the London Literary Gazette, an excellent journal which is deservedly popular.” Unlike its model, it lasted for only fifty-two issues (Pyle 140).

Two periodicals stood out from the plethora of imitators. The first was Charles Westmacott’s The Gazette of Fashion, Magazine of the Fine Arts, and Belles Lettres, published from February 1822 until January 1823. The second, eventually to have a defining role in the decline of the Literary Gazette and thus on Jerdan’s life, was the Athenaeum, this latter magazine commencing only in 1828.

Looking back, Jerdan dismissed The Gazette of Fashion saying merely that it was “nearly occupied with attacks on me and the Literary Gazette and did not last long” (3.211). The long passage of time between the appearance of Westmacott’s vicious journal and Jerdan’s reminiscence had mellowed his memory. In fact, The Gazette of Fashion flagrantly and continually attacked Jerdan and his magazine. In the fourth issue, on 23 February 1822, appeared a twelve-verse song to be sung to a well-known air. The title was “The Tears of Longman’s (alias the Literary) Gazette.” The refrain “When this Gazette was new”, purported to extol the hope of high standards offered at the outset of the Literary Gazette and mourn the bitter disappointment that Westmacott suggested resulted from its actual performance. The first verse set the scene:

When this Gazette was new,

(Tho’ that’s not many a year,)

We had, (tho’ strange ’tis true)

A prospect of good cheer.

But now our wit decays,

The public proves a shrew,

And is wiser now-a-days,

Than when this Gazette was new.

Referring to the well-known practice of Longmans to have weekly meetings, Westmacott did not resist the opportunity to make fun of this, too:

> Then J….n every week

With L….n went to dine…

and

J….n seeks his source,

And L….n looks quite blue….

Westmacott brought into his verse the Literary Gazette’s well-known attack on Byron, and put into Longman’s mouth the words: “Whate’er books you attack/Pass eulogies on our’s.” In this, and more specific ways, he held up to ridicule the Literary Gazette’s so-called puffing of its partners’ books, about which there is more to say as the Gazette proceeded. Westmacott’s vituperation was unmistakable, subtlety was not his way:

But now in vain we puff,

The public wind the trick,

And all cry out ‘Enough,

Much more will make us sick.’

We sound the Pirate’s praise,

But ah! It will not do:—

How diff’rent were the days,

When this Gazette was new!

The very public feud grew worse. In issue No.10, in April 1822, The Gazette of Fashion printed a “Reply to the Duffing Coterie Longman’s Duffing Gazette and the Mohawk Magazine”. Eschewing his name, which indicates that Jerdan was well-enough known for readers to identify him, Westmacott wrote: “Callous as we thought him, our ‘rack of satire’ has extracted a groan from the chief of Literary Duffers. He pleads to our charge… we believe that there are more than one person attached to Longman’s Duffing Gazette, who not only have an ‘itching palm’, but reason for hire, like the rhetoricians of Athens, on two sides of political and literary questions, at one and the same time.” The accusation of bribery is plain enough. In response to the Literary Gazette’s attribution of imitation, The Gazette of Fashion responded: “First this Mohawk asserts that The Gazette of Fashion is an imitation of the Literary Gazette…God forbid that we should imitate any thing so maudlin and so vile, so brutally stupid and so impotently dull! We beg our readers to bear in mind that the Gazette of Fashion, from the commencement, has admitted nothing but original papers. It has not been filled like the Duffing Gazette, with thirteen pages of extracts, repeatedly dished up, and three pages of advertisements, principally relative to the book-making manufacture of the proprietors.” There was some truth in Westmacott’s accusation about the content of the Literary Gazette, but the fact remains that the original journal lived on long after the Gazette of Fashion had disappeared.

Westmacott continued to make his spurious claims a few months later, boasting that his sales had risen rapidly, with back numbers being reprinted. He claimed too, to have “exposed crippled and palsied the Duffing System”. He called on his readers to sing triumphantly that he had bested the opposition: “That the Duffing Gazette should have the meanness to refuse our advertisements, was to be expected from its grovelling littleness.” This was something of an own goal for Westmacott, who had advertised his Gazette in the pages of the journal he vilified and seemed surprised when Jerdan rejected further advertising. In his May issue Westmacott attacked various types of literary men, and could not resist a gibe at a (rather glaring) error made in that week’s Literary Gazette which, published on Saturday, critiqued an actress’s performance not delivered until the following Monday. In June 1822 Westmacott disposed of his interest in the Gazette of Fashion, and for a while Jerdan and his journal were left to carry on in peace, reaping the benefits of Landon’s labours in growing circulation. In 1827 Westmacott purchased The Age following its proprietor’s bankruptcy, and ran it until 1834, continuing his trademark accusations.

The rising circulation caused pressure on space allotted to advertising; Jerdan allowed only advertisements directly connected with literature and the arts, but especially when Parliament was sitting, he had more demand than his space provided. Accordingly, he announced an occasional increase from 1-3 columns over his normal allotment, but pointed out that at other times the usual two pages were not filled, so the average would stay much the same. The issue for 16 March 1822 assured readers that they would not lose by this policy amendment as the type had been changed, and the current number “contains as nearly as possible one third more matter than a Number of the year 1819…without detriment to the beauty of the sheet or the clearness and facility with which it may be perused!” As Jerdan was not known for his financial acuity, it may have been Longmans who suggested this increase in advertising revenue, as they were keeping the accounting records of the Literary Gazette. It made sense to take advantage of the increased circulation of the journal, largely created by L.E.L.’s poetry. A few months later Jerdan noted that a reader had suggested placing advertisements on a separate sheet so as not to encroach upon the magazine proper. The Stamp Act prohibited this, however, but the alteration in type, he claimed in February 1823, gave the reader one-fourth more matter than it had originally (29). The onerous Stamp Act was not finally abolished until 1855.

Vital to the success and increased circulation of the Literary Gazette, its star poet Letitia Landon was often beset by illness, by spasms, and, a theme recurring in her writing, thoughts of suicide. Her strong emotions, flowing into poetry, were a new and exciting experience for readers of the Literary Gazette, sensing a power of expression hitherto unknown from the pen of a very young woman. Paradoxically, although sharing the very essence of herself with the unknown thousands of her fans, Landon cherished her privacy, needing time to be alone, to write and to think, and several of her poems describe this need. Perhaps fortunately for the secrecy of her affair with Jerdan, Landon had no confidantes, and indeed, her friends were frustrated by her apparent self-containment.

If the readers of the Gazette had known what has now been revealed, that Landon and Jerdan had become lovers, they would have reacted very differently to the poem that appeared on 4 May. Jerdan recognised it as a key work; it is the one he referred to in his reminiscence of L.E.L. at this time as “excited…by the Sapphic warmth”. The first poem in the second series of Poetic Sketches, L.E.L.’s “Sappho” looks back to a tradition of works upon this subject as far back as Ovid. Landon, however, changed the story in a crucial – and with hindsight, obvious – way, introducing an older man as Sappho’s first love, “and attributes the magnetism of Phaon, her second and fatal love, to his resemblance to this unnamed man who, as Sappho’s former tutor, occupied a role identical to that of Jerdan vis-à-vis Landon in 1822” (Lawford 270). Jerdan could not but understand that ‘Sappho’ was meant for him:

one had called forth

The music of her soul: he loved her too,

But not as she did – she was unto him

As a young bird, whose early flight he trained,

Whose first wild songs were sweet, for he had taught

Those songs –but she looked up to him with all

Youth’s deep and passionate idolatry:

Love was her heart’s sole universe – he was

To her, Hope, Genius, Energy, the God

Her inmost spirit worshipped….

He was moved by her image of herself as a young bird, using it twice in later life, once in a letter after L.E.L.’s death, attributing to her the words “we love the bird we taught to sing”, a line he repeated as an epigram in his Autobiography. No poem of L.E.L.’s has this precise line, but the image of the singing bird being trained by its teacher, harks directly back to Sappho. Landon’s poetic references to young girls tutored by older men, implied in the “Fate of Adelaide” and explicit in Sappho, must have flattered Jerdan, giving him further encouragement, if any were needed, to pursue the affair. From his point of view he was the wellspring of inspiration from which her poems emanated so prolifically, a view that Landon herself justified by the many oblique references made to him in her works.

Edward Bulwer (later: Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton). G. Cook after Richard James Lane.

Popular and successful as she was becoming for her regular appearances in the Literary Gazette, Landon was experiencing difficulties at home. Her mother thought her conduct with Jerdan was unbecoming and improper. Following bitter arguments, as reported by Katherine Thomson to Bulwer Lytton, “Mrs Landon to this day looks upon Mr Jerdan as the source of her separation from her daughter. As a mother myself, how could I blame her interference?” (Quoted Lawford 277). Both Catherine Landon and the poet’s close friend of later years, Katharine Thomson, believed Landon to be utterly virtuous, never suspecting any sexual connection with Jerdan. Just to be accused of improper behaviour with him was, Landon implied, highly offensive to her dignity, and it was for this reason that she left home. The rift with her mother lasted almost up to the time of Landon’s death, when one visit and one letter were all that is known to have passed between them. Cousin Elizabeth, the tutor of her younger years, remained living with Landon’s mother until the latter’s death in 1856, both of them suffering considerable poverty. Elizabeth died four years later. Leaving her father was painful to Landon, and several of the poems appearing in the Literary Gazette during the summer of 1822 confirm this.

Landon moved to her grandmother Mrs Bishop’s establishment in Sloane Street. This made life easier for her, allowing more freedom of movement, and also the opportunity to establish herself as an independent woman in society. Letitia Bishop had a private income, sufficient to support her granddaughter for a while, until Landon’s writing started to earn her a living. It is entirely possible that she was well aware of Landon’s affair with Jerdan, especially if she read the poem appearing in the Literary Gazette of 18 May 18, entitled “Rosalie”:

We met in secret: mystery is to love

Like perfume to the flower; the maiden’s blush

Looks loveliest when her cheek is pale with fear.

Living with her grandmother gave Landon a context of respectability, although quitting her parental home was likely to have raised some eyebrows. Life was more fun now; she adored her grandmother, made frivolous caps for her to wear, and was allowed to have friends to visit. Jerdan was often among the visitors, stopping in most days for only a few minutes, longer on Sundays when he could review her manuscripts. Such personal attention was not the norm for a frantically busy editor, in demand from authors, politicians, publishers and printers. However, she was the star to whom the success of the Literary Gazette was hitched, so his frequent visits could, if necessary, be justified.

Now that she was not under her mother’s disapproving gaze, Landon was able to go into society more; her companion and escort was frequently Jerdan. He had an endless supply of free tickets and invitations to shows of all kinds – freak shows, panoramas, animal displays, museums, exhibitions, theatres and concerts – everything that London had to offer was his to enjoy. Everyone courted the Literary Gazette editor, with an eye to a ‘notice’ in the magazine which would attract more visitors to their entertainments. In his self-appointed role as tutor, Jerdan was happy to take Landon to exhibitions of paintings, an art form he especially enjoyed, and one which was a direct inspiration for her poetry. Even before this period in her life, Landon had taken pictures and engravings as her subjects, and now she was seeing them at first hand, enhanced by the company of her great love. These outings were an important part of their lives for several years, and were uppermost in Jerdan’s mind when he came to write about L.E.L. in his Autobiography:

The world was only opening and unknown to her, and she might – even holding her child-like gratitude in view – both feel and say, “For almost every pleasure I can remember I am indebted to one friend. I love poetry; who taught me to love it but he? I love praise; to whom do I owe so much of it as to him? I love paintings; I have rarely seen them but with him. I love the theatre, and there I have seldom gone but with him. I love the acquisition of ideas; he has conducted me to their attainment. Thus his image has become associated with my enjoyments and the public admiration already accorded to my efforts, and he must be all I picture of kindness, talents, and excellence. [3.172]

These were not, of course, Landon’s own words, but were put into her mouth by Jerdan, perhaps not for self-aggrandisement, but as a way of reassuring himself of the happy times they had shared, although when writing his book he was in a period of deep unhappiness.

Landon accompanied Jerdan not only to exhibitions of paintings, but also to the various ‘shows’ of the time. Charlatans showed mermaids cobbled together from disparate animals and fish, to deceive the viewer, and a merman was displayed, denounced by the Literary Gazette of 26 June 1824 as “a fish tail, an ape body, the head formed of the wolf-fish, the skull of an ape and the fur of a fox” (411). It was the age of the “-ramas”(meaning ‘sight’); the Cosmorama was a peep-show where magnifying lenses enlarged small panoramic landscapes. When it moved to Regent Street, the Gazette of May 10 1823 noted disapprovingly that it became “a more agreeable lounge than ever for the various ranks which may be comprised by titles of Idlers, Lovers, Young Folks, Amusement-Seekers, Ice-eaters etc. etc.” The 24 March 1825, the Gazette called the Nurorama a “trashy exhibition…you are allowed to look through glasses at miserable models of places, persons and landscapes, while two or three nasty people sit eating onions and oranges in a corner of the room” (188). The Diorama also came in for criticism from the Gazette, complaining about the lack of realism in the images shown. “For example, in this picture, when the waves rise and fall, why are the vessels stationary?” (4 September 1824, 573). The Diorama was built in four months at a cost of ten thousand pounds, the precursor of yet more “ramas”, such as the British Diorama, the Octorama and Padorama, causing the Literary Gazette to comment, “the family of Ramas is already large, but it will soon increase to an extent which no verbal Malthus will be able either to limit or to predict, if its members are to be distinguished, like the streets of Washington, by numerical prefixes” (579).

Waxworks had been popular for some time, a major exhibit being staged at Exeter `Change in the Strand since 1812. This building, just opposite Jerdan’s office, displayed “The London Grand Cabinet of Figures” (Altick 339). By 1825 waxworks were being used in pseudo-science, to the utter disgust of the Literary Gazette whose issue of last day in 1825 complained: “Under the pretence of imparting anatomical knowledge, this filthy French figure…is exhibited…as remotely from anatomical precision or utility as any of the sixpenny wooden dolls which you may buy at Bartholomew Fair…The thing is a silly imposture, and as indecent as it is wretched” (843).

Left: The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly designed by P. J. Robinson. 1811-12. Photograph 1895. The Hall, which was torn down in 1905, was at 170/171 Piccadilly. Right: The Theatre Royal, Haymarket, by John Nash. 1820. London.

One of the more bizarre shows was engineered by Bullock at the Egyptian Hall. As part of a doomed venture to domesticate reindeer in England to provide venison and furs, Bullock imported a Lapland family to “drive a sledge around the Egyptian Hall against a suitably painted background, with sledges, snowshoes and domestic utensils scattered around the room” (Altick 31). Bullock took one hundred pounds a day in the first six weeks, but in January the Literary Gazette reported that the family were dejected and dilapidated. In March the journal noted that 58,000 visitors had come to see the Laplanders. Jerdan accompanied the exiles to the Haymarket Theatre and remembered “their ecstasies whilst the orchestra were tuning their instruments, only equalled by their disappointment and dislike when they came to play a tune. Lap (sic) ears preferred discord to harmony, beyond all comparison” (2.88). Much later, perhaps rather ashamed of the misery inflicted on this family, Jerdan recorded that they were returned to their native land “wiser, richer, and happier than any Lapps had been since their earliest migration” (Men I Have Known 74).

One of the consequences of becoming more involved with the entertainments on offer, was that Landon began to write up some of the reviews, perhaps even those just quoted, thus taking some work off Jerdan’s hands. It was also at this time that she took over reviewing some of the books that were sent to the Literary Gazette. As reviews were unsigned, it is not known definitely who wrote which review, but it would seem that Landon’s pile included “publications in general literature, principally in the provinces of poetry, fiction, and romance”. Her help was invaluable to Jerdan, and continued for a “number of years”, according to Jerdan himself, “for she delighted in the work to the extent of craving for the employment, reading everything voraciously, forming opinions, and adding to her stores of knowledge, writing skilfully, and often beautifully upon her favourite subjects, and, in short, doing little less for the Gazette than I did myself” (3.173). According to Glennis Byron’s biography in the DNB, “as the Gazette was one of the most influential journals of the time and had a notable influence on the sale of the books reviewed in its pages, Landon wielded a significant amount of power in this role, contributing to a decline of a number of literary reputations,” Landon may certainly have written sharp reviews to works she did not think of merit, but the final say was Jerdan’s, who would not have published a poor review of something he thought did not deserve it. Kindness was his trademark, and he would have had to be convinced of Landon’s reasons – she did not have quite the power attributed to her. It appears doubtful that she was adequately and properly paid for the work she undertook; maybe she did it for love, as a way of legitimately being closer to Jerdan on a daily basis, in a joint venture that was open and above-board. In a tally of Landon’s earnings, Jerdan gave two hundred pounds as the total she made over ten to twelve years for all her contributions to periodicals and annuals, a niggardly amount for her huge output.

Few accounting records exist from this period of Longmans publishing house, which handled all pay for the Literary Gazette’s writers between 1820-1841 (Pyle 126). Jerdan’s pay in 1820 for editing every three issues of the Gazette was twenty-one pounds, that is seven pounds per issue, or three hundred and sixty-four pounds a year. For comparison, one can point out accoriding to the DNB that in 1821 Thomas Campbell was paid £500 a year for editing Colburn’s New Monthly Magazine, although the sub-editor did most of the work. There was clearly no recognised pay scale for contributors. It may have been that Jerdan was allowed a total rate per issue to pay his writers, and had to juggle the fees to spread the total as thinly as possible; in this regard Landon would have been low down in his priorities as she was happy for the work, had a roof over her head at her grandmother’s, and for the moment did not have to rely on her earnings for a livelihood. He probably also weighed in the balance all the benefits she derived from his company in the way of outings and society events, and considered this a part-payment for her work.

Poems about paintings were a common theme for Landon, so in the summer when Jerdan introduced her to his close friend the artist Richard Dagley, who also wrote occasionally for the Literary Gazette, she wrote three poems entitled “Sketches from designs by Mr Dagley,” published in the issue published on 20 August 1828. It is the third of these, “The Cup of Circe” that may mark the start of her actual, as opposed to imaginary, affair with Jerdan. The lines were blatantly seductive:

And by his side a girl, whose blue eyes, bent

On the seducer, looked too innocent

For passion’s madness; - but lover’s soul was there –

And for young Love what will not women dare!

The metaphor of the “Circean cup” was in currency at the time – Jerdan used the phrase himself: “The Circean cup was gently replenished” (4.16), and it was well known that he was an enthusiastic drinker. Moreover, the “seducer” in L.E.L.’s poem was “a white-haired man”, hanging on the brim of her wine cup. But who was really the seducer, and who the seduced? In the affair of Jerdan and Landon, it seemed an unanswerable question.

In the same issue of the Literary Gazette appeared Isadore, a story by L.E.L., of a nineteen-year old girl falling for a man for whom “the day of romance was over; a man above thirty cannot enter into the wild visions of an enthusiastic girl”. Landon was a few days from her twentieth birthday, Jerdan had turned forty in April. Placed in the “Sketches of Society” column the story was more serious than was usual in that feature. Landon killed off her heroine who had been rejected, unable to get closer to her beloved than watching him with his “elegant equipage” and his “delicate wife”. This is the first expression in Landon’s work showing “that her tragic thrust is aimed at the shallow heart of London society” (Lawford 294-06). Feeling herself to be somewhat outside of society, Landon had reason to think herself special. Her poems were like none written by a woman before, they were a song of love to her illicit lover, she was living a double life, hiding behind her mask. Jerdan, on the other hand, was a working journalist and editor, who would be vilified by his readers should the truth be discovered. He subscribed whole-heartedly to the myth of L.E.L.’s specialness, keeping up this belief thirty years later when he came to confront the subject of L.E.L. in his Autobiography: “Of the gifted being. I cannot write in a language addressed to common minds or submitted to mere wordly rules. I must appeal to the feeling and the imaginative; for such was L.E.L. She cannot be understood by an ordinary estimate nor measured by an ordinary standard” (3.168).

Identifying herself with the ‘outsider’ in a society which she had only recently entered, Landon was strongly influenced by De Staël and Byron. She admired John Keats and Percy B, Shelley, and in this was again ‘outside’ the bounds prescribed for virtuous young ladies, who were forbidden to read these poets. The Literary Gazette was particularly vocal on the matter of morality, and Jerdan insisted that he published nothing that could not be read by young ladies, nothing that could upset their moral code. Jerdan did not want anything to do with Shelley and his subservience to love, and in reviewing Queen Mab Jerdan distanced his magazine, advising “A disciple following his tenets would not hesitate to debauch, or after debauching, to abandon any woman” (Lawford 298). At first glance this would seem to be extremely hypocritical of Jerdan. He may not have “debauched” Landon in the sense that she was an unwilling partner, but he had definitely taken her virginity, compromised her position in society, and her immediate chances of making a suitable marriage. At second glance it has been suggested that both Landon and Jerdan saw social conventions as not applying to them, that they should join forces in combatting conformity (Lawford 298). This vision of themselves as apart from the common people also found voice in a poem Landon contributed to the Literary Gazette in September, in which the man who adores a princess is pitied and mocked by the common people: “They little knew what pride love ever had/In self-devotedness.”

By September 1822 Landon’s poetry became altogether darker, the first time she had her heroine poison or kill her lover, and penned one of many poems in which the heroine commits suicide. Reading such a poem would have disturbed Jerdan deeply, but his loyalty to her did not waver and in fact got in the way of his literary judgement when, in October, he put L.E.L. on the same pedestal as the long-established famous poet Felicia Hemans; he put the two of them above a pair of unnamed women poets aspiring to the readers’ approbation, complaining that he had difficulty finding material good enough to fill his sheet, (other, of course than his protégée’s, was what he didn’t say). Comparing L.E.L. directly with Hemans in this way threw into vivid contrast her sexually-inspired warmth against the other’s more commonplace verse (Lawford 307). Her success in the Literary Gazette had the effect of encouraging other periodicals to take women poets more seriously, opening more widely for them doors that had previously remained reluctantly ajar.

Poems about pictures were a common theme for L.E.L., quite an achievement in a magazine which did not print the illustrations from which the poems derived, and she wrote another which appeared in the Literary Gazette of 16 November. This assuredly related directly to her affair with Jerdan, although the visual image was one popular at the time: “Lines Written under a Picture of a Girl Burning a Love Letter,” something Landon must have routinely done with Jerdan’s personal notes, which would have been too dangerous to keep. As far as is known, none have survived. In her poem, the woman fears that love will be destroyed by secrecy.

In the meantime however, Jerdan and the Literary Gazette were still the focus of the appalling Westmacott, who, earlier in the year, had jeered at him with “Tears of Longman.” As the attacks had subsided for a few months, Jerdan would have hoped that was the end of it. The truce was not to last long, however. In November the front page of the Gazette of Fashion carried a highly personal, abusive attack which may have been written by Westmacott himself although he was no longer the owner of the paper, or by someone whom he highly influenced. In a reverse kind of way, this attack throws a light on the regard in which Jerdan was held by the publishing community.

The article went on to acknowledge the Literary Gazette’s right to praise works without merit, as the public could make up their own mind about the works concerned; it took issue however, when the Gazette defamed and injured an individual to gratify its prejudices, an act vulgar and contemptible, and to correct which the Gazette of Fashion leapt to the injured party’s defence. All this hyperbole was an irony after it had criticised Jerdan himself so publicly and violently. Their complaint, it turned out, was a review of the actor Kean’s performance, and quoted some of the Literary Gazette’s lines, which were indeed pretty brutal. The Gazette of Fashion deduced that, as had happened before, the reviewer had not actually attended the performance, and ended with the slashing comment that “It is rather fortunate for Mr Kean that the Literary Gazette is not consulted for theatricals, or looked up to for a candid opinion upon any subject.”

The Literary Gazette and Blackwoods supplied different markets, but there was often cross-fertilisation as Jerdan and Blackwood sent each other books to ‘notice’, the question of who was first to review being always a matter of pride. His tie with Henry Colburn was, from the beginning, a trial to Jerdan. Colburn was a publicist for the books he produced, and expected the Literary Gazette to rave about each of them, whatever the reviewer's true opinion. Jerdan insisted on independence, but in the event rarely gave a Colburn book a negative review. These concerns were a constant irritant, shown up in a letter he wrote to Blackwood in March 1823. “I hope you feel that the Literary Gazette is under no trammels as to the notice of your publication. I assure you the suspicion of that fact was utterly without foundation, as I would not endure a silk thread over my Editorship for any advantage it would bring.” If Blackwood wanted early reviews, he must send early copies. Furthermore, Jerdan had had to borrow a volume from Croly in order to review it, and demanded of Blackwood, “you should now send me a copy as droit and not put me to the expence of a purchase to replace what was besoiled at the Printers so as to be unfit for a Gent’s library.” To avert any offence Blackwood might take, Jerdan wound up his letter telling him that “Ebony’s lucubrations are mighty favourites with me in general, and I take your little flaps occasionally with the best of good humour.” Jerdan was often the butt of what he called ‘flaps’ here, and ‘flings’ in a later letter.

Whilst the competition was real, there was still a cameraderie between the two Scottish editors, unfortunately not reflected in Jerdan’s relationship with his own partner. Colburn was the constant thorn in Jerdan’s side, the latter often finding himself between writers and the publisher. Barry Cornwall wrote in March, “I don’t see any Advertisement of my book. Colburn is determined to do as little as possible for it…It is just like you to take the vexation so good-naturedly – that little Colburn – but I won’t rail at him now” (National Library of Scotland, 4010/205-6). The Literary Gazette had gained great influence in the few years since Jerdan became Editor. Alaric Watts, who had worked for Jerdan for the past three years, advised William Blackwood in 1821: “It is without exception the best advertising medium for books there is….I would hint that it is worth your while to be upon civil terms with Jerdan, as he has it in his power to render essential service to your publications. A review in the Gazette is of use as an advertising medium” (Letter B. Procter to W. Jerdan, 26 March 1823, MsL C8213je2 Iowa). Certainly Colburn used the Gazette as an advertising tool for his publications, in a manner which caused Jerdan much trouble as time went on.

As an antidote to the petty squabbles and rivalries that were his every-day fare, Jerdan continued his close involvement with the committees and council of the Royal Society of Literature. Finally, in June 1823 following endless meetings, amendments, quarrels and tussels, a document setting out the Constitution and Regulations of the RSL was presented to the King. The whole enterprise was clearly important to Jerdan, as over thirty years later his memoir went into considerable detail concerning the specific aims, their realisation, and the donations, legacies and annuities gifted to the Society. However, he didn’t take it all too seriously, seeing the humour in an altercation which ensued over the name by which members could be designated, in line with the other Royal Societies. One or two of these Societies objected to the use of ‘Fellow’ for the RSL, and the Royal Academy argued against M for Member, as was their own designation. The ludicrous situation was eventually resolved by the adoption of a four-letter title, rather than the three used by the other institutions, and “MRSL” was agreed.

A sociable and always amiable man, Jerdan enjoyed larger-than-life people, and one for whom he had some affection and esteem was Rudolph Ackermann, a German bibliophile, pioneer of lithography, and publisher of fine colour engravings, notably “The Microcosm of London”, published monthly between 1808-10. A large, heavy man, eighteen years Jerdan’s senior, Ackermann was “sagacious and energetic, good-natured and liberal, simple and far-sighted” (Pyle 89 quoting Oliphant). His vast knowledge and odd manners impressed Jerdan, as did his heavily-accented language, of which Jerdan made gentle fun. Jerdan dined with Ackermann often when he lived at 101 Strand, then moving to Camberwell, and thence to Ivy Cottage in Fulham Road. Surely at one of these bibulous dinners, Jerdan told Ackermann how he had watched from the deck of the Gladiator as Nelson’s body was brought home on HMS Victory, and in return Ackermann recounted that he had designed Nelson’s funeral carriage and the emblems on the Admiral’s coffin. Ackermann held “blue parties” where literary ladies outnumbered the gentlemen. Jerdan said that these artistic and literary conversazioni, which served to introduce artists to patrons, were the first in London and were subsequently enthusiastically imitated. Being of a charitable bent himself, Jerdan praised Ackermann’s tireless efforts to raise money for the relief of widows and orphans in Germany, raising more than forty thousand pounds (4.241).

Ackermann was of a generous nature, but when the Literary Gazette reviewed a publication of his somewhat critically, he was offended. He told Jerdan he had delivered some ‘muzzle’ (Moselle) to Grove House (Jerdan’s home from 1825), on his way home to Fulham, and thought the review was a poor return, a “shlapp in the mouth” (4.243). Jerdan asserted that even had he known at the time, the gift would have had no influence on the tone of his review. He was prepared, and indeed happy, to receive gifts and benefits in kind, but recoiled at the notion of accepting “the gross shape of money”, seeing this as a form of prostitution. Here, he parted company from a rival editor Leigh Hunt, who “would ‘as lief have taken poison’ as accepted a free [theatre] ticket” (Holden 28). Hunt pioneered independent theatre reviewing at a time when a notice was in effect an advertisement, in other words, a “puff”.

Jerdan had been approached by publishers Rodwell and Martin to edit an annual, then unknown in England, following a successful German model, with many engravings. Finding that the cost could not be less than one thousand pounds, the idea was abandoned. Here, Jerdan missed a golden opportunity to be the editor of the very first annual, a position which could have made a great difference to his fortunes. However, Ackermann saw the possibilities of such a plan and in 1822 had published the first annual, the Forget-Me-Not, spawning a genre which had many imitators and which, for a short time, were immensely popular and profitable, despite the high costs. Not all annuals met the high standards of Ackermann’s Forget-Me-Not. Jerdan snarled that some of the imitators were filled “by the names of celebrated authors who sold at a high price their names and sweepings of their studies for the advertising baits of A, B, or C, their contribution being public disappointments, and nearly all the rest of the starved book being unpaid mediocrity” (4.242). Jerdan contributed to several of these annuals himself as time went on, but was not then in a position to take such an elitist view.

Landon’s risky habit of addressing her poems to Jerdan continued. In the first three months of 1823 inventors T and H Thomson advertised their set of twelve sealing wafers in the back of the Literary Gazette. In the same issues, Landon wrote her series “Medallion Wafers,” an early example of product placement. The seals were of classical subjects, and maybe for this reason Jerdan also ‘noticed’ them in his Fine Arts column. L.E.L.’s poems on the seals adopted the conceit that they were used for love letters, musing that “Here’s many a youth with radiant brow/Darkened by raven curls like thine”. A “youth” Jerdan was not, but he did possess a fine head of “raven curls”. Another in her series harked back to the Circean cup, the wine that the lover was so attached to:

She held the cup; and he the while

Sat gazing on her playful smile,

As all the wine he wished to sip

Was one kiss from her rosebud lip.

No writing of Jerdan’s hints at any untoward relationship with L.E.L. save with the hindsight of knowledge of their affair, the part of his Autobiography discussing her, and his Memoir of her, are full of the emotion of an old man looking back on a past, lost love. However, at the time, he was not too careful when he treated her, in the Literary Gazette, as someone apart from the other contributors. As a footnote to a poem praising L.E.L., in the magazine of 29 January 1823, Jerdan let slip that he regarded L.E.L. and himself as editor of the Gazette, as one entity. He says that publishing this tribute to the poet “is something like self-praise by the Literary Gazette, but the many tributes we receive to the genius addressed in these lines will escape censure, when we acknowledge them as due to a young and female minstrel, and expressive of feelings very generally excited by her beautiful productions.” He did not eulogise like this about his other contributors, mostly male, so this departure from his norm risked attracting too much attention. On the other hand, he had financial as well as personal interest in boosting L.E.L.’s public profile to keep his readers avid for more from her pen.

Early in 1823 Landon prepared a volume for publication the following year, under the title . Later she told Alaric Watts, “I wrote the Improvisatrice in less than five weeks and during that time I often was two or three days without touching it. I never saw the MS till in proof-sheets a year afterwards, and I made no additions, only verbal alterations.” At the same time she produced “Leander and Hero,” appearing in the Literary Gazette on 22 February, once again blatantly exposing the affair with Jerdan:

And then their love was secret, - oh it is

Most exquisite to have a fount of bliss

Sacred to us alone…

Love’s wings are all too delicate to bear

The open gaze, the common sun and air.

Or, she again implied, the understanding of the “common people”. This was risky in the extreme, trumpeting the affair under the collective nose of the readers in a style never before seen in women’s poetry. It was risky too on Jerdan’s part, to publish it, flaunting his perpetual claim that nothing in the Literary Gazette was unsuitable for the eyes of well brought up young ladies. It looked like a game of ‘Dare’, chancing that L.E.L.’s devoted audience were so besotted with her by now that they looked no further than the surface of her emotional poetry. It was a private game, too. F. J. Sypher, who edited Landon’s correspondence, argues, “We must never forget that love poems for the Gazette functioned as a part of Landon and Jerdan’s affair; that she held up to him images of miserable women left alone who yet kept on loving, while, whatever else he did, Jerdan kept returning to her.”

In early April Landon became pregnant, unable to confide in anyone except Jerdan. As the year rolled on however, her changing shape did not go unnoticed. The situation was ripe for mockery. Although Jerdan’s nemesis, Westmacott, had moved on from the Gazette of Fashion, he had not finished with taunting Jerdan. The editor was not his only target; Westmacott appears in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography described as “journalist and blackmailer”, allegedly extorting money from those who wished their names to be either omitted from his paper, or to clear their name from his allegations. He had been well paid by the King’s supporters to vilify Queen Caroline, during the 1820s, which did not prevent him from turning his bile on the King later.

It was perhaps rather spiteful and foolish of Jerdan to give space for a notice of Westmacott’s slim book, Points of Misery published in 1823. This collection of “chiefly original” work by Westmacott was under ten headings of Miseries, such as Authorcraft, Travelling in a Coach, Matrimony etc. The Literary Gazette review on 15 November jibed “It is a point of misery beyond any here adduced, to be obliged to read such sad and silly trash as these”. Selecting a few (very minor) grammatical errors, the notice opined: “the letter-press [text] is altogether so contemptible as to be below notice.” George Cruikshank’s accompanying etchings were praised, sympathising that he had “such poor materials to labour on”. The review concluded that “The handsome paper and printing of the work form a contrast to its slang subjects and low composition.” Such a negative and cutting notice was tantamount to lighting the blue touchpaper to Westmacott’s fiery temper. He published Cockney Critics with a dedication to William Jerdan as Editor of Longman & Co’s Literary Gazette. Taunting, he opened with a quotation from Dryden:

To hear an open Slander is a curse,

But not to find an Answer is a worse.

His dedication declared that the satire which followed had two motives, to draw attention to Jerdan’s name, and “to display both your name and character in its true light”, hoping that the old-fashioned style of dedication would obtain for Jerdan “that notoriety to which your peculiar qualifications have so eminently entitled you.” He accused Jerdan of having too high an opinion of himself as a censor and judge of literature. He was “a slaughterman of reputation, and you can flay poor authors with as much facility and something less of feeling than a carcase butcher does the bleating lamb.” (Contrary to his intention, Westmacott thus confirmed to posterity the extent of Jerdan’s importance and influence in the literary world.) Westmacott’s diatribe was peppered with angry epithets: he belaboured Jerdan’s “Billingsgate style”, mentioned his “ravings on the Fine Arts”, called him a “nameless thing” and “a hired oracle of an anti-literary faction”. He fomented the row over Byron, citing the editor of the Examiner who noted Jerdan’s dismissal of Heaven and Earth, and reluctance to pay a shilling for three Cantos of Don Juan. Westmacott compared this with the eightpence price of the Literary Gazette, “sixteen pages of little else than a mass of unconnected extracts from about a dozen books.” The accusation of Jerdan’s taking bribes which he had expressed earlier in The Gazette of Fashion surfaced again here, as did his anecdote about the review of an actress who had not yet given her performance.

Hatred and bile pour out of this so-called “Dedication”. Jerdan’s writings, he said, were “impregnated with sulphurous spirit”; he was obnoxiously sarcastic to those who “have not paid tribute to the Mohawk chieftain of the Cockney literati”. For himself, said Westmacott, he was not to be bullied by such a reviewer, jeering that the “trifle” of his which received a poor review in the Literary Gazette was received and sold well elsewhere, thus proving “the best reply to your slanders and is a sure criterion of your critical abilities.” Jerdan often remarked, throughout his Autobiography, that a critic cannot but offend those whose work they either find fault with, or fail to review at all. Westmacott’s revenge is an overwhelming example of a writer so offended, and it was over such a “trifle” that he instantly sat down to write his “Dedication” and attack on his enemy. He stated unequivocally that he had long been an enemy of Jerdan’s and had “eagerly sought an opportunity of exposing you, upon public principle alone,” but his footnote to this sentence was more to the point: in case his readers missed the earlier attack on Jerdan, Westmacott explained that The Gazette of Fashion, when he was its proprietor, “exposed” the tricks of “honest William Jerdan and his associates”, but he had then been subjected to steps taken by the “coterie” to silence him. The Reverend Croly allegedly threatened legal proceedings, though Jerdan himself, taunted Westmacott, “dare not” open his mouth at the time. Instead, Jerdan is accused of “pining in secret over his misery for two years” and had finally found an opportunity for revenge “by pouring out his exuberance of bile in a personal attack upon the author of Points of Misery”. Had Jerdan in truth been harbouring such a grudge against Westmacott, he would have come up with a rather stronger notice of his rival’s negligible book. Furthermore, Westmacott’s vicious attack was very personal, accusing him of “cowardice natural to your character” and of being an assassin, like a tiger springing upon defenceless prey. For him to point the finger at Jerdan’s “revenge” is a blatant case of the pot calling the kettle black. In fact, Jerdan’s review concerned Westmacott’s work, not the man himself, and was hardly severe enough to be the fruit of two years’ resentment, as Westmacott suggested.

Moving on from the personal, Westmacott set out his “general charges” against Jerdan: that, being the “hired servant of certain booksellers” (identifying Longman & Co., Colburn and Jerdan as owners of the Literary Gazette), he must “protect their interests and puff up their publications”. Forestalling any response from Jerdan, he rejected any claim that Jerdan had only a share in the work,and was “uncontrolled”, on the basis that the major owners were “two great publishers” and, as a junior partner, Jerdan could not act in opposition, by giving impartial or critical reviews of Colburn and Longman’s books. Indeed if he were to do so his partners would withdraw, with adverse effects upon the Literary Gazette and its Editor. (Westmacott’s prognosis turned out to be correct, but this was far in the future.) Not only was Jerdan guilty of ‘puffing’ his partners’ publications, raged Westmacott, but also of denigrating those of their rivals which were in competition against them., charging that this was “a shameful and degrading practice…it is a bold union of hypocrisy, malice and ignorance, and a weekly libel upon genius and common sense.” Concluding this Dedication, Westmacott declared it an honour to oppose such a man as Jerdan, “whose censure is the highest possible praise – and whose scurrilous abuse is the best passport to good society”, and he challenged Jerdan, “Cease, viper! You bite against a file.”

Westmacott then launched into the body of his work, a series of verses. The first, an Introduction to the Satirist, did not refer to his target by name, but his meaning was unmistakable:

The foe of genius, learning’s pest,

A pick-fault, scurvy hack at best,

Who spreads pollution o’er each page,

And lives detested by the age.

And then

Be mine the honour to expose

The worst of all poor authors’ foes,

The BLOW FLY critic, senseless fool,

The DEALER’S HACK, and willing tool,

Who drudges on through slime and gall,

And lives, to die abhorr’d of all.

Raising a head of steam in his next section, entitled The Blow Fly, Westmacott indulged in a torrential thesaurus of terms such as murky, filthy, vile, heartless, base, pest, curse, fungus, noxious, foul, slimy and so on:

’Tis he, the BLOW FLY, critic hack,

Assassin like behind your back,

Who’ll use the poignard pen;

You’ll trace him by his slimy track

From ******** to the Row and back,

Where kindred tigers den.

Turning his furious spotlight away from Jerdan, Westmacott went on to denounce “Cockney Critics” in verse and “Cockney Criticism” in prose, railing yet again on his old topics of puffing reviews, partner publishers promoting their books and suppressing independents. “The Coterie” in rhyming couplets harped on a similar theme, followed by “Address of the Cockney Chief to the Coterie”, replete with footnotes to strengthen his case against these detested men, especially mentioning Blackwoods and “a fraudful Scottish band”. He also hit directly at William Gifford, editor of the Quarterly Review,

Who doth usurp a sov’reign dominion

O’er me, and all the sooty saucy host

That under L**gm**’s banners are enroll’d

To puff their publications in Gazette…

Westmacott’s loathing for Jerdan went so deep as to imagine his enemy’s death:

Here rage and envy chok’d his breath,

His tongue was speechless, pale as death

His visage: Anon – his giant frame

Convulsive heaved, with grief and shame;

His eye-balls, starting, glar’d around,

He fell, unpitied, on the ground.

Hysteric laughter filled the room,

The critic’s requiem to the tomb.

Even after killing Jerdan off, Westmacott turned his venom on to George Canning who, he said, rose in status “by the wit of his tongue”. However,

Tho’ now he vents his spleen at a second-hand stall,

And prints with his neighbour at Blunderhead Hall

At least, ’mong the wags, ’tis currently said

‘Canning’s silver is visible through Jerdan’s lead’.

A sweet reciprocity, tho’ much on one side,’

And that is not George’s – these intimates guide.

Will fathers the Minister’s jokes with a grace,

George gratefully gives to Will’s offspring a place;

And ’tis said, but I know not how far it is true,

Will, himself, has a something worth having in view.”

The author’s footnotes to this passage confirm Blunderhead Hall as “Jerdan’s villa at Brompton”, and “Will’s offspring”, as “A son of Jerdan’s is, I hear, in the Office of the Secretary for Foreign Affairs – One good turn deserves another.”

Recalling the vituperation to which he was subjected, Jerdan admitted thirty years later that he had kept a copy of Cockney Critics, which still annoyed him then as it had done on publication. Not a man to avoid unpleasantness, he printed Westmacott’s scurrilous Dedication and some other quotes from the work for the benefit of contemporary readers, to illustrate the level of opprobrium he had faced. However, he went on to recall “that the Gazette and its Editor, so serviceably reviled, reaped every beneficial consequence which was naturally to be expected – the former advancing rapidly in circulation, and the latter being (it might be unduly) more highly appreciated in social and literary life” (Lawford 334)./p>

In Jerdan’s Autobiography he loudly rejected accusations that the Literary Gazette was a mere tool of the publisher owners. There is no reason to disbelieve him, as by that time he had no connection with the journal and nothing to lose by telling a different story. However, “Nothing could be more untrue than this libel” he claimed. “From first to last I never admitted a whisper of control” (3.221). In support of this, he quoted a letter from Cosmo Orme, partner in Longman & Co., referring to an unfavourable review of a Colburn book in the Literary Gazette. “Our co-partner may be sore; but the lady deserves all she got; and these independent articles do us a world of good”, wrote Orme. On another occasion a particular review offended Mr Longman, who told Jerdan that if he could not be positive, he should refrain from any review at all. Jerdan, believing that his journal should report fairly on current literary works, refused to follow this practice, but even so it was widely believed that he followed Longman’s precepts. It was of little comfort to him at the time that “I had frequent proofs in my possession where the very parties who spread the report were absolutely prostituting their own service venally to publishers” (3.112).

Jerdan’s journalistic experience had taught him to be on the look-out for scoops for the Literary Gazette. He had already made good contacts among the men who had sailed with Captain Parry on his expedition to the Arctic on the Hecla and the Griper, publishing their accounts in his paper. Talking of Alexander Fisher’s Journal of the Hecla, Jerdan “procured the publication and saw [it] through the press”; although he does not mention any payment for this, it was another occasion on which he acted as agent for an author. When the expedition returned from their second journey in October 1823, Jerdan took advantage of his friendships and was permitted aboard the ships at Woolwich, on a Wednesday morning, coming up with them to Deptford, where they moored. Amid all the bustle, he managed to acquire much information and arrived home late and tired that night. By working fast and furiously, he was able to give a good account of the expedition in the Saturday’s Gazette, with a sequel the following week. His strenuous exertions earned an increase of seven hundred copies, so that at the end of 1823 the print run of the Literary Gazette was four thousand (3.112).

Reliable circulation figures for the Literary Gazette are hard to come by, and those given by Jerdan in his Autobiography should be treated with caution, as he tried to remember events from a distance of two decades. In comparing figures from Longmans and from Jerdan discrepancies arise, so the following figures should be taken as a guide rather than as a precise statement of fact. In his Autobiography Jerdan mentions first year sales of 1250 copies, being 1000 stamped and 250 unstamped. This must be a weekly figure, as in the Literary Gazette of 16 June 1821, stamp purchases for 1817 were given as 53,600, an average of a little over a thousand a week. Stamp purchases for 1818 were given as 31,700 and for 1819 as 49,000. By 1820 there were 50,037 stamped copies. Jerdan claimed that unstamped sales were double those for stamped copies, which would mean a printing of 150,000 copies during 1820, an average of 2885 a week. This calculation is largely supported by Longmans’ ledgers for January 1820 which show 2000 stamped and about 300 unstamped copies, plus a trade in parts and volumes (3.111). Just as Tuckey’s Voyage to the Congo had increased sales by 500 in 1817, here, discussing his feature on Fisher’s Journal, Jerdan claimed an increase of 700 copies, raising the Gazette’s print run to 4000 at the end of 1823. It therefore seems probable that by comparing the 1820 average of 2885 a week with the pre-Fisher’s Journal figure of 3300 a week, the circulation of the Literary Gazette had been boosted by 400 copies a week, which coincides with the increased amount of L.E.L.’s poetry that it contained (Longmans’ Archives. Ledger 1819-1843).

According to Amy Cruse’sThe Englishman and His Books in the early Nineteenth CenturyBlackwood’s claimed in 1820 that its circulation was ‘somewhere below 17,000’, the Edinburgh upward of 7000 and the Quarterly about 14,000. The Gentleman’s Magazine was about 4000. His figures cannot be taken as very reliable” (191). Ms Cruse does not mention the Literary Gazette anywhere in her survey, despite its undoubted influence on the reading public.

Exhausted by his labours, and by the constant attacks he had suffered, Jerdan inserted a half-joking note in the Literary Gazette of 27 December 1823:

The want of an Editor for the Literary Gazette is immediately anticipated, the present incumbent being nearly smothered to death under reams of heavy poetry accumulated from weekly loads. Candidates may send in their estimates of their own talents (if they admit of measurement); the wages are liberal, but no fees are allowed to be taken for advice, though it is daily asked under every possible shape of circumstances.

Four days later, Jerdan and L.E.L.’s daughter was born. (Information from Michael Gorman, from a diary note by Ethel Barnes.)

Bibliography

Altick, Richard A. The Shows of London. Cambridge, Mass. & London: Belknap Press, 1978.

Cruse, Amy. The Englishman and his Books in the early Nineteenth Century. London: George Harrap & Co., 1930.

Duncan, Robert. “William Jerdan and the Literary Gazette.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 1955.

Holden, Anthony. The Wit in the Dungeon: A Life of Leigh Hunt. Little, Brown, 2005.

Jerdan, William. Autobiography. 4 vols. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co., 1852-53.

Jerdan, William. Men I Have Known. London: Routledge & Co., 1866.

Landon, L. E. Romance and Reality. London: Richard Bentley, 1848.

Lawford, Cynthia. “Diary.” London Review of Books. 22 (21 September 2000).

Lawford, Cynthia. “Turbans, Tea and Talk of Books: The Literary Parties of Elizabeth Spence and Elizabeth Benger.” CW3 Journal. Corvey Women Writers Issue No. 1, 2004.

Lawford, Cynthia. “The early life and London worlds of Letitia Elizabeth Landon., a poet performing in an age of sentiment and display.” Ph.D. dissertation, New York: City University, 2001.

McGann, J. and D. Reiss. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Pyle, Gerald. “The Literary Gazette under William Jerdan.” Ph. D. dissertation, Duke University, 1976.

Rappoport, J. “Buyer Beware: The Gift Poetics of L.E.L.” Nineteenth Century Literature. 58/4 (March 2004).

Sypher, F. J. Letitia Elizabeth Landon, A Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2004, 2nd ed. 2009.

Watts, A. A. Alaric Watts. London: Richard Bentley, 1884.

Westmacott, C. M. Cockney Critics. J. Duncombe, 1823.

Last modified 21 June 2020