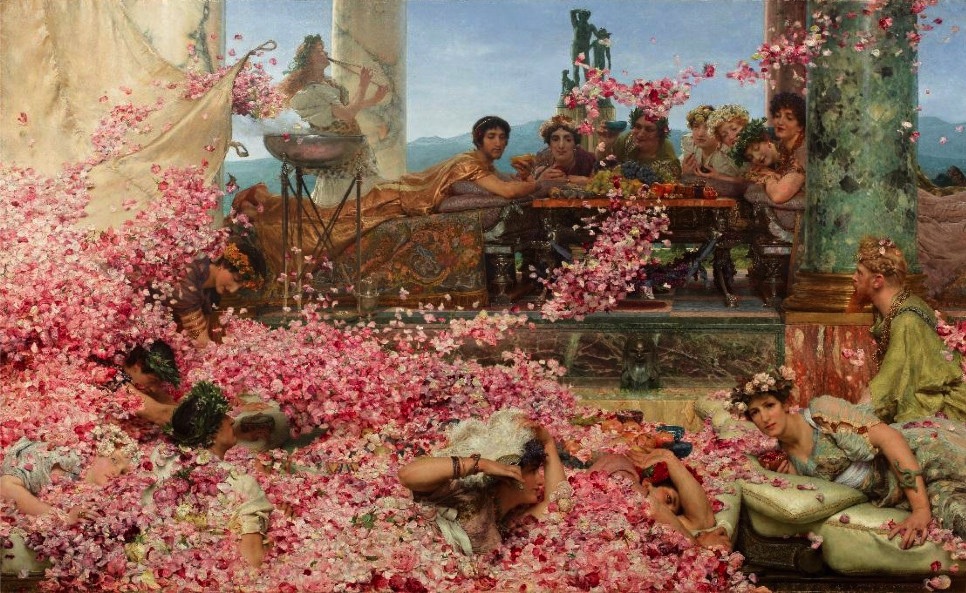

In historic pictures much depends on the choice of subject. In the Academy of 1888 there was a scene from Roman history by an eminent painter, Mr. Alma Tadema. It was entitled "The Roses of Elagabalus." In its own sphere and range of art, it was a picture of unquestionable power, and it was at once purchased for an immense sum of money; yet it can hardly fail to awaken very painful reflections.

Let us try to describe it.

The Roman emperor, Elagabalus, or Heliogabalus, who had been a priest of the Syrian sun-god, and was justly murdered at eighteen, was the most execrably infamous of human kwretches. At one of his feasts he had the ^wriuin, above his dining-hall, suddenly let loose, to shower tons of roses on his parasites, some of whom, it is said, were suffocated by the flowers, and drawn dead from beneath the mass.

Such is the scene painted by Mr. Alma Tadema, and with marvellous power in imitating gold, silver, marble, jewels, and human splendour, debased in the person of Elagabalus to tho1'.i','y-e--fc depths of all that is earthly, and devilish. Roses, yes! a torrent of them; and what a divine thing a rose is! "If there were but one rose in all the world, and a man could make it," said Luther, "we should deify that man." In one of his finest poems, Victor Hugo, after speaking of the passion, despair, and fury which sometimes rent his heart in exile, when he thought of the tyranny and oppression which is in the world, ends the poem with the words, "I take a rose�I look at it�and I am appeased." Yes! a rose is a divine and perfumed miracle of God; it may awake in a holy soul thoughts too deep for tears. But the humblest rose that ever had the dew of morning on its pure leaves, is worth the whole avalanche of these sickening, crumpled, decaying blossoms for vile purposes vilely abused.

And Youth, which, as the poet-preacher says, "dances like a bubble nimble and gay, and shines like a dove's neck, and the colours of the rainbow, which hath no substance, but of which the very colours and image are fan- tastical," why are we asked to look on this its inexpressible degradation?Elagabalus! — there lies that shame and monstrosity of the human race, the loathly boy-emperor, on his couch of silver and mother-of-pearl, in his long golden Phoenician robe, leaning on cushions stuffed ivith the small plumes of partridges; his intriguing and hideous grandmother, Julia Mcesa, and other hard-featured women beside him; he leering over his wine-cup at the bejewelled wretches below him, while the fittest unconscious comment ,on the whole scene is the hideous head of the bronze monster, which grins like a demon, just above. An historic painting, truly!�but what history! In all the stately and noble scenes of Roman rule, its lofty figures, its heroic ideals, its magnificent magnanimities, the all but Christian grandeur of its endurance and its patriotism, was there nothing worth the infinite toil of this skilled hand but this carnival of bejewelled sensualism, this portent of abysmal depravity, this avalanche of wasted roses over the dazzling banquet of the world, the devil, and the flesh — that banquet where the dead are there, and the guests in the depths of hell.

Related material

References

Farrar, Archdeacon [F. W.]. "Historic and Genre Pictures." Good Words. (1888?): 542-43.

Last modified 8 February 2007