The Marley Door-Knocker in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol (1843)

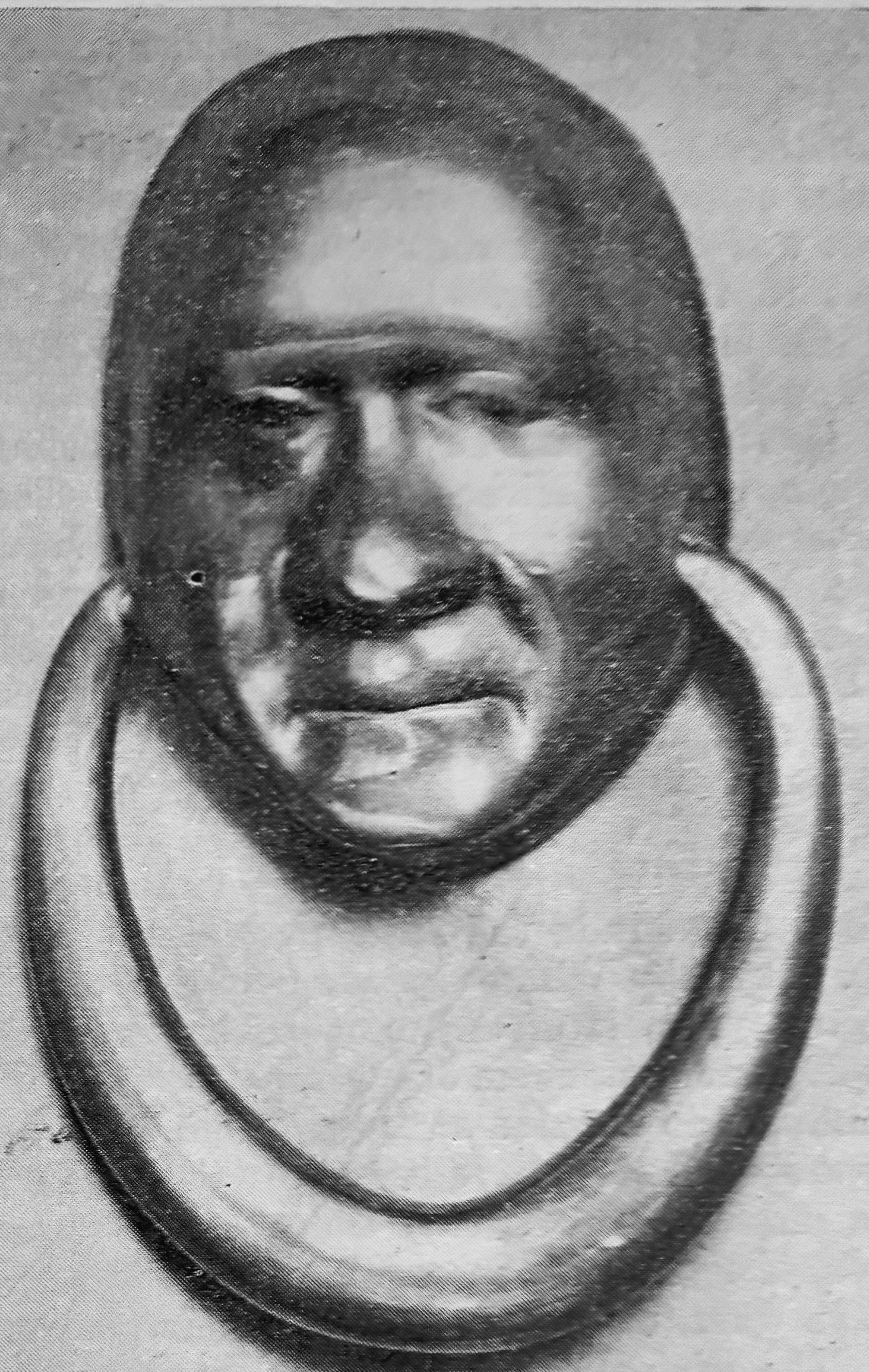

Left: Charles Green's 1924 lithograph, page 29, with a vignetted area of 7.2 cm by 5.5 cm, Scrooge's Knocker. Right: from the October, 1924, Dickensian, The Marley Knocker (brass, before 1840).

Context of the Illustration: The Transformation of the Door-knocker

Now, it is a fact, that there was nothing at all particular about the knocker on the door, except that it was very large. It is also a fact, that Scrooge had seen it, night and morning, during his whole residence in that place; also that Scrooge had as little of what is called fancy about him as any man in the city of London, even including — which is a bold word — the corporation, aldermen, and livery. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of his seven years' dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change: not a knocker, but Marley's face.

Marley's face. It was not in impenetrable shadow as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Scrooge as Marley used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air; and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid colour, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part or its own expression.

As Scrooge looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again.

To say that he was not startled, or that his blood was not conscious of a terrible sensation to which it had been a stranger from infancy, would be untrue. But he put his hand upon the key he had relinquished, turned it sturdily, walked in, and lighted his candle.

He did pause, with a moment's irresolution, before he shut the door; and he did look cautiously behind it first, as if he half-expected to be terrified with the sight of Marley's pigtail sticking out into the hall. But there was nothing on the back of the door, except the screws and nuts that held the knocker on, so he said "Pooh, pooh!" and closed it with a bang. ["Stave One: Marley's Ghost," 1843 edition, pp. 19-21]

Commentary: Dickens's Source for the Marley Knocker in A Christmas Carol

he first "Stave" in the first of the Christmas Books (December 1843) underscores Ebenezer Scrooge's

abrupt shift from mundane, workaday existence into the spiritual dimension of human

existence by the sudden transformation of his own door-knocker into the face of his dead

business partner, Jacob Marley. Long used to the knocker of what had formerly been Jacob

Marley's front door, Scrooge has given no thought to his dead partner for seven years.

Entering the metaphysical portal that the ghost seems to open, Scrooge emerges from his

night's adventures with the Spirits of Christmas a new man on Christmas morning.

he first "Stave" in the first of the Christmas Books (December 1843) underscores Ebenezer Scrooge's

abrupt shift from mundane, workaday existence into the spiritual dimension of human

existence by the sudden transformation of his own door-knocker into the face of his dead

business partner, Jacob Marley. Long used to the knocker of what had formerly been Jacob

Marley's front door, Scrooge has given no thought to his dead partner for seven years.

Entering the metaphysical portal that the ghost seems to open, Scrooge emerges from his

night's adventures with the Spirits of Christmas a new man on Christmas morning.

As J. Ardagh notes in his brief 1924 article, the first of Dickens's highly popular Christmas Books had a number of nineteenth-century iterations: of the slender Chapman and Hall volume alone "There are at least three different issues: (1) 1843, blue and red, t.p.; (2) 1844, blue and red; and (3) 1844, green and red" (204). He notes programmes of illustration by Appleton, Barnard, Copping, Everett, Michael and Rackham.

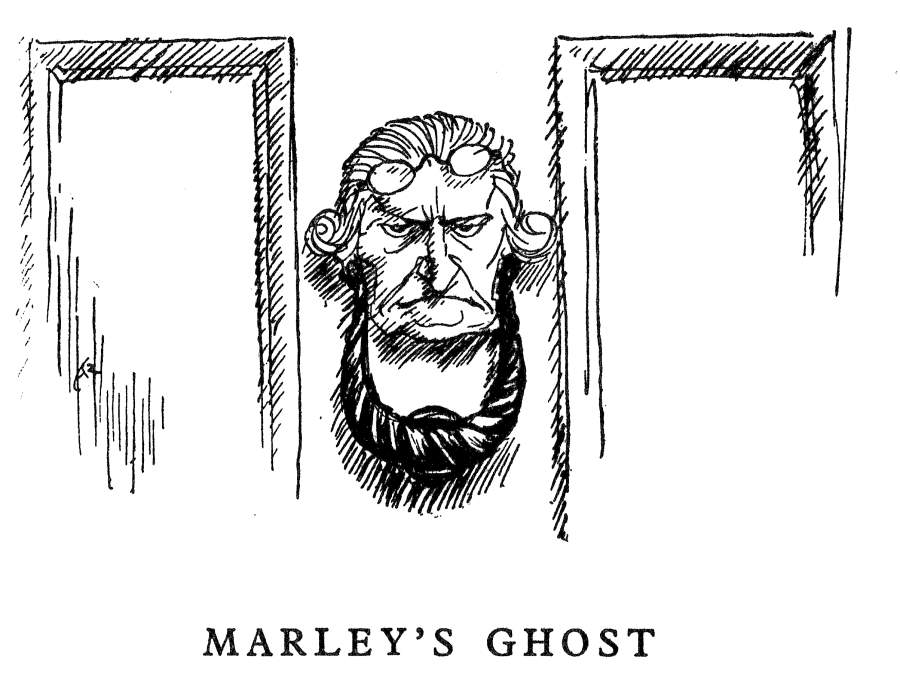

And yet few illustrators of the novella have provided a close-up realisation of the knocker, the exceptions being Charles Green, Sol Eytinge, Jr., and Arthur Rackham. Both of the 1870s Household Edition illustrators, Fred Barnard and E. A. Abbey, having the space for only a few illustrations, like Leech in the first edition chose to depict Scrooge's reaction to the Ghost as Scrooge sits, trying to get comfortable in front of a fitful fire in his apartments after the disturbing initial visitation. Neither Eytinge's realistic treatment, with Scrooge in a topcoat and carrying an umbrella as he approaches his door, nor Rackham's study of the sour-faced knocker itself in a simple pen-and-ink drawing, captures the psychological dimension of Scrooge's sudden confrontation with the metaphysical world — and neither possesses Harry Furniss's abundant humour. However, the expression on Marley's face in Rackham's drawing suggests the ghost's dissatisfaction or discomfort with having materialised as a door-knocker. Nor (significantly) do any of the pictorial realisations actually reflect the real knocker in The Strand (not Cornhill) that likely inspired Dickens in the autumn of 1843.

Scrooge's warehouse must have been near Cornhill as Bob Cratchit 'went down a slide there 'twenty times' before proceeding to his residence art Camden Town. Scrooge's chambers were evidently a relic of the days when merchants lived at their place of business as Fezziwig did. [Ardagh, 204]

The knocker was supposedly on the door of a house in eighteenth-century Craven Street, off the Strand. Dickens's passing it regularly as he visited his publishers, Chapman and Hall, likely inspired one of the most memorable scenes in the Dickens canon. T. W. Tyrrell in "The 'Marley' Knocker" in the Dickensian (1924) has proposed that Dickens's transforming the bronze door-knocker into Marley's face was directly influenced by an unusual knocker with a man's face, that in fact of the house's owner, Dr. David Rees, "who lived at No. 8 for many years, and no one [among the neighbours] ever doubted that it was the identical knocker in which Scrooge saw Marley's face." Although lion-knockers were the norm, the original owner, perhaps for the sake of self-promotion, chose to have an image of himself greet clients upon their arrival. The tradition that the knocker was Dickens's source persisted, despite the fact that Green's realisation, for example, deviates from Dickens's verbal portait, with no "ghostly spectacles turned up on its ghostly forehead," although Green's knocker does have "hair . . . curiously stirred. . . ." Despite the fact that Dickens's verbal portrait does not resemble Dr. Rees's knocker, neighbourhood tradition held that it was the original. However, the unwanted attention that the door consequently received throughout the rest of the nineteenth century resulted in a later owner's having it taken down and placed in a bank vault in 1899.

Even had any of the various illustrators known about this "original," they have (perhaps for psychological purposes) elected to depict the face as if it were a reflection of Scrooge's own, rather than a portrait in bronze of a smooth-faced, balding, middle-aged man with a bland expression. Note, for example, how Sol Eytinge makes Scrooge and Marley virtual twins in Marley's Ghost, the only significant difference being the glasses which the spirit is wearing both here and in Marley's Face, which bears a strong resemblance to the Marley knocker in Appleton's 1924 watercolour, the illustration that may well have inspired Tyrrell's article.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843, 1868, 1910, and 1912 Editions

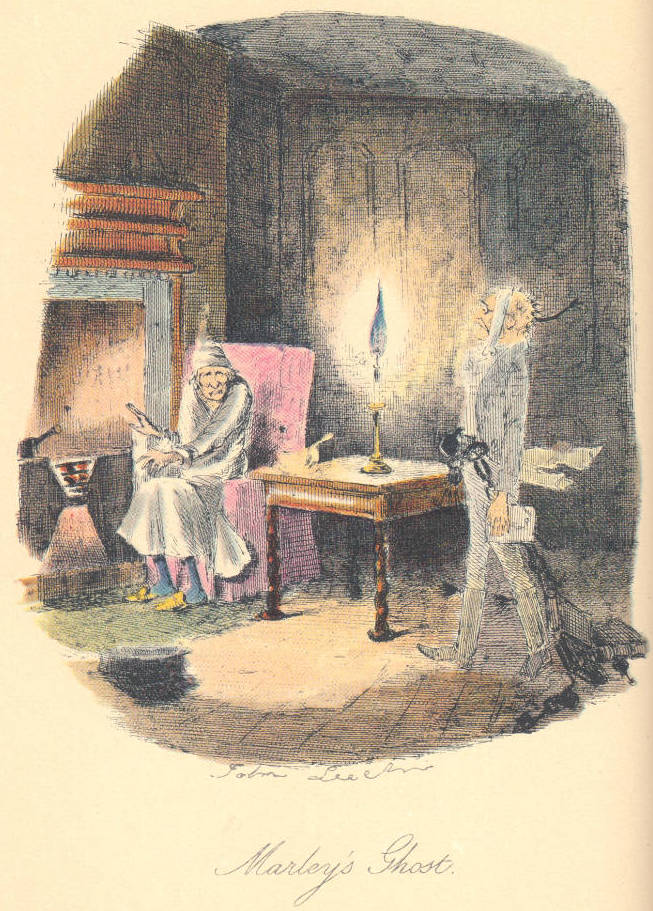

Left: Eytinge's scene of Scrooge's shock at seeing Old Marley's likeness on his own door, Marley's Face (1868). Left of centre: Leech's interpretation of the arrival of the shade of Scrooge's former partner, Marley's Ghost (1843). Right of centre: Furniss's The Ghostly Knocker (1910), featuring a psychologically magnified version of the knocker. Right: Arthur Rackham's simple line-drawing of the dour-faced knocker, Heading to Stave One (1912).

Related Material

- The Christmas Books by Charles Dickens, 1843-1848

- Dickens — "The man who invented Christmas"

- An Introduction to A Christmas Carol

- Dickens's Childhood Experiences and A Christmas Carol — An Introduction with Discussion Questions

- Sympathy and the Spirit of Capitalism in Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Ebenezer Scrooge to the Charity Collectors — "Are There No Prisons . . . Are There No Workhouses?"

- Scrooge

- Sympathy for the Poor and Christmas Present — An Introduction with Discussion Questions

- Sentimentality: The Victorian Failing

- Two Contemporary Responses in The Illustrated London News

- Washington Irving and Dickens's A Christmas Carol

- Vocabulary Notes for A Christmas Carol

- Recent editions particularly useful for students and scholars

- Recent editions particularly useful for students and scholars

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Naming of Names in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol." Dickens Quarterly 4:1 (1987): 15-20.

Ardagh, J. "Some Notes on A Christmas Carol." The Dickensian 20.76 (October 1924): 204.

The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Guiliano and Philip Collins. 2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. X.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. VIII.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Vol. III.

Hearne, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1989.

Patten, Robert L. Dickens, Death, and Christmas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. 344 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-286266-2. [Review]

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to A Christmas Carol." The Christmas Books, 2 vols. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978. Vol. 1, 33-36.

Thomas, Deborah A. Chapter 4, "The Chord of the Christmas Season." Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982, 62-93.

Tyrrell, T. W. "The 'Marley' Knocker." The Dickensian 20.76 (October 1924): pp. 202-203.

Created 9 January 2026