Although the traditional Punch-and-Judy booth is now only occasionally seen at British seaside towns such as Brighton, in the Victorian era the pedestrian might catch a Punch-and-Judy act on any street corner in any good-sized city in the three kingdoms. Imported from Italy in the seventeenth century, the text and stock characters of the Punch-and-Judy show reached their present form about 1800, but may go back as far as the popular masked mimes of ancient Greek and Roman theatre. "Pulcinella" in commedia dell’arte became "Polichinello," "Punchinello," and then simply "Mr. Punch." Such shows, appealing not just to children, have their immediate roots in the commedia dell’arte plays of sixteenth century Naples, especially those that included the beloved and irascible rascal, Punchinello. Itinerant "professors" such as Dickens's Codlin and Short in The Old Curiosity Shop (25 April 1840-6 February 1841) have entertained English-speaking audiences at least since the 1662, when Samuel Pepys attended and subsequently recorded in his famous Diary a performance in London by Italian puppeteer Pietro Gimonde, whose stage-name was "Signor Bologna." Because Pepys recorded the date of that show as 9 May 1662, it has come by tradition to be known in the United Kingdom as “Mr. Punch’s birthday.”

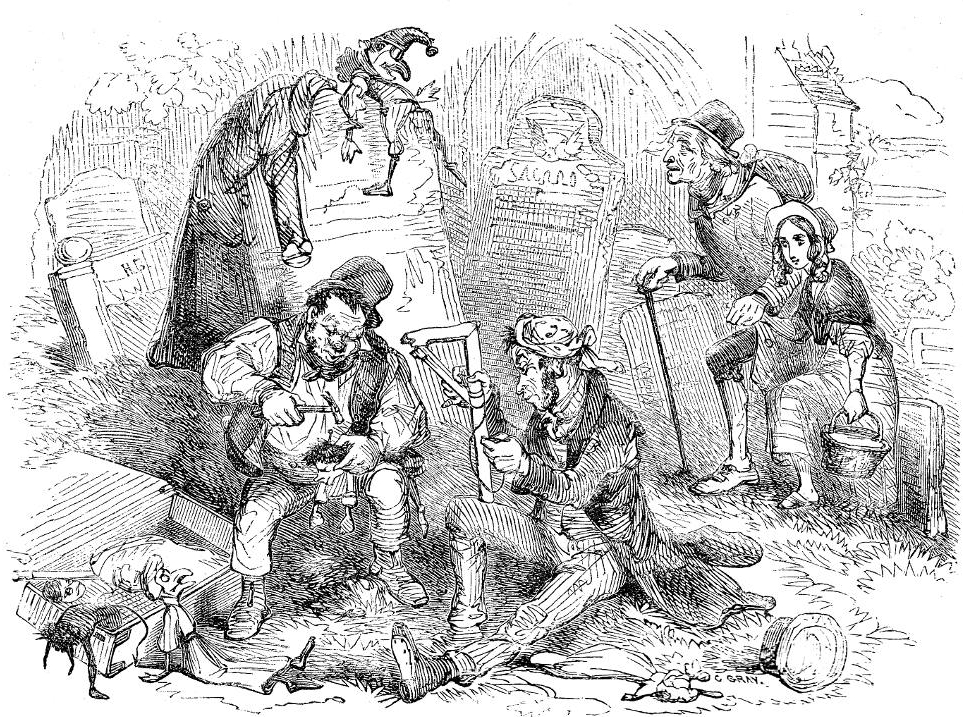

The stock characters of the hot-tempered, hook-nosed, hunch-backed protagonist and his termagant wife (Judy) share the tiny stage of the booth with a well-known series of antagonists: the Baby, Crocodile, Devil, Priest, Doctor, Police Officer, and Hangman. A peculiar feature of the children's puppet show is the usual presence of a live dog, a terrier named Toby, who, dressed in a ruff, stations himself at the edge of the stage for the entire performance. In The Old Curiosity Shop, Chapter XVI, Charles Dickens uses the free-and-easy itinerant performers and their hand-to-mouth existence as a complete contrast to the relatively stable life that thirteen-year-old Nell Trent and her grandfather have enjoyed in the curiosity shop that Quilp has forced them to flee. In a country churchyard near an inn frequented by itinerant thespians, The Jolly Sandboys, the Trents encounter a pair of puppeteers mending their kit:

In part scattered upon the ground at the feet of the two men, and in part jumbled together in a long flat box, were the other persons of the Drama. The hero’s wife and one child, the hobby-horse, the doctor, the foreign gentleman who not being familiar with the language is unable in the representation to express his ideas otherwise than by the utterance of the word "Shallabalah" three distinct times, the radical neighbour who will by no means admit that a tin bell is an organ, the executioner, and the devil, were all here. Their owners had evidently come to that spot to make some needful repairs in the stage arrangements, for one of them was engaged in binding together a small gallows with thread, while the other was intent upon fixing a new black wig, with the aid of a small hammer and some tacks, upon the head of the radical neighbour, who had been beaten bald. [160-62]

Left: Clayton J. Clarke's amusing caricatures of the Punch-and-Judy performers in the Player's Cigarette card series: Codlin (Card No. 25) and Short (Card No. 25), both dating from 1910. Right: Harry Furniss's realisation of the same scene in the Charles Dickens Library edition, Codlin and Short in the Churchyard< (1910).

Thus, in his fourth full-length novel (1840-41) Dickens introduces his heroine and readers to two of his most famous minor characters, the Punch-and-Judy men Tommy Codlin (who carries the portable theatre on his back and keeps the accounts) and the originator of many of the voices of the commedia dell’arte characters, Harris (otherwise, "Short" and "Trotters"). The pair are on their way to the July thoroughbred races, one of seven racecourses held annually from 1840 onward at Newmarket, part of the itinerant performers' circuit in the south of England. Dickens does not use the traditional term for the puppeteers, “Professors,” but accurately describes their kit.

Above: Phiz's realisation of the the wayfarers' encountering the popular entertainers repairing their puppets in the churchyard, Punch in the Churchyard from Master Humphrey's Clock (11 July 1840).

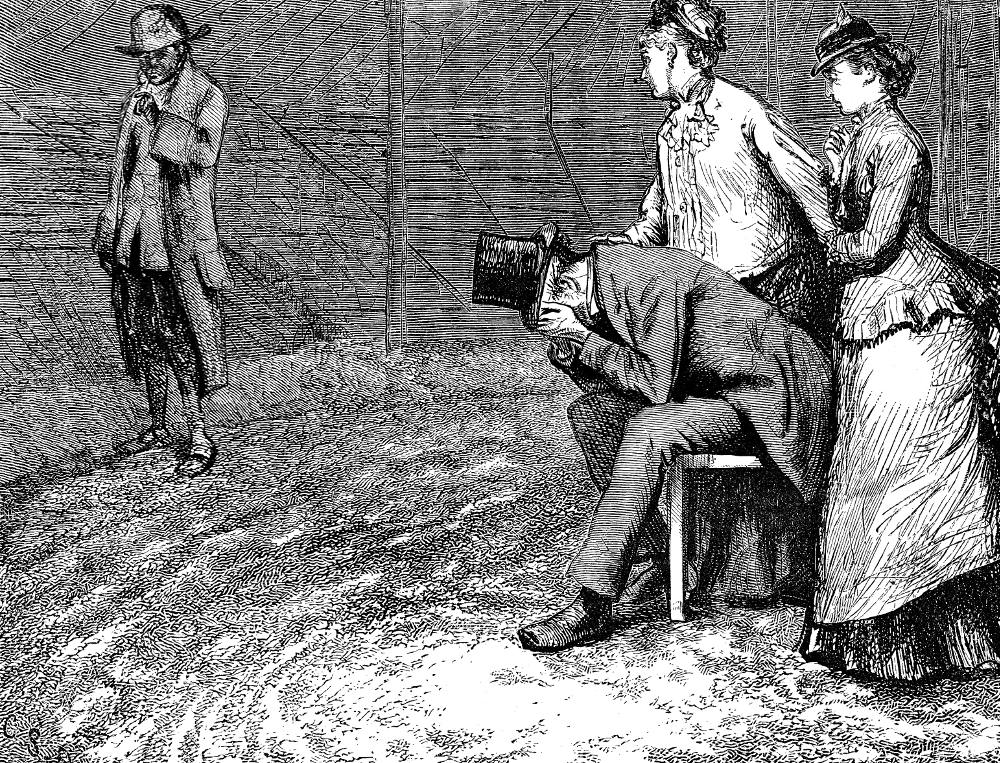

Above: Charles Green's less whimsical Household Edition illustration focuses on the casual nature of the puppeteers in Nelly, kneeling down beside the box, was soon busily engaged in her task (1876).

Dickens, Theatricals, and Popular Entertainments: "People mutht be amuthed"

From his earliest outings with his father, John, Charles Dickens was used to being in the limelight, singing the popular song "The Cat's-Meat Man" from tabletops in public houses in Chatham, Kent. According to David L. Gold, the famous novelist was “not just a political and social reformer, a writer, an editor, and a newspaperman, but also a playwright, an actor, a producer, a director, a stage manager, and a member of the audience at numerous theatrical performances, both professional and amateur, both public and private, Dickens had an unwaning passion for thespianism from his early years to his dying day” (239-40). He was not merely a writer and literary personality: he was a performer in the century's most popular one-man show: The Charles Dickens Reading Tours of Great Britain, the United States, and Canada. No wonder then that his earliest novels betray his life-long interest in such popular entertainments as strolling players, street musicians, and, in particular, Punch-and-Judy shows.

As Peter Ackroyd notes in his biography, throughout his life he felt some kinship with even such tawdry street performers as itinerant Punch-and-Judy men. In November 1849, for example, in the midst of grinding out the monthly instalments of David Copperfield he wrote a letter to the papers in defence of "Street Punches, the Punch and Judy acts which were performed at street corners and fairs" (576), and then, just a few days later, described the heroine Dora Spenlow's father as looking "like Punch." Although he himself never attempted puppeteering, Dickens thoroughly enjoyed being a conjurer, an amateur magician, and a children's entertainer his whole life: he was never far from private theatricals, and converted the children's schoolroom at Tavistock House, London, into "The Smallest Theatre in the World," which he explicitl;y designed for the entertainment of friends and family, many of whom performed alongside Dickens on its diminutive stage. It held an audience of only twenty-eight, about the size of the audience to which Punch-and-Judy men catered on the sidewalks and in the parks.

Dickens's strategy in the post-London chapters of The Old Curiosity Shop of having the wayfarers encounter so many itinerants associated with the entertainment industry offered his team of illustrators numerous opportunities for interesting caricatures of dancers, acrobats, puppeteers, and all those other hangers-on at such events as the horse-races at Newmarket, Suffolk, in July. The pictures of George Cattermole and Hablot Knight Browne contrast again and again Nell's innocence and inexperience with the street-wise but kindly itinerants who constitute the fellowship of the road: "If Nell's progress takes her from the wilderness of the city across anormal landscape populated by curious characters — by Codlin and Trotters and their Punch and Judy figures, by the Grinder with his "lot" travelling about on stilts, by Jerry and his dancing dogs, by retired giants (or stories about them) who wait upon dwarfs at meals — that same progress carries her later across a more phantasmagoric backdrop. There she passes factory cities where she felt 'a solitude which has no parallel but in the thirst of the shipwrecked mariner' (413)" (Home, 497).

In describing the circusses, fairs, boat-trips, theatres, and tea-gardens, Dickens's eye is focussed as much on the audiences as on the entertainment, frequently isolating the family party for his attention — as in his account of Astley's in Sketches by Boz. His stance is that of the tolerant observer, amused by human foibles, but happy to see people enjoying themselves. [Cunningham, 22]

Above: Phiz's realisation of the Nubbles family outing to a popular entertainment, At Astley's (3 October 1840).

After the generally positive view of popular entertainments implicit in the Nubbles family's outing to Astley's Hippodrome in Chapter 39 and indeed throughout The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens neglects popular entertainments in his novels for over a decade, until he introduces Sleary's Circus in Hard Times (1854). Denouncing by implication the anti-entertainment dogma of the Evangelicals, Dickens's circus-master pleads with the dour philanthropist and industrialist Thomas Gradgrind to recognize the moral and emotional value of the low-brow theatrical entertainments that dominated Dickens's fourth novel:

"Thquire, thake handth, firtht and latht! Don’t be croth with uth poor vagabondth. People mutht be amuthed. They can’t be alwayth a learning, nor yet they can’t be alwayth a working, they an’t made for it. You mutht have uth, Thquire. Do the withe thing and the kind thing too, and make the betht of uth; not the wurtht!" [Book the Third, "The Garnering," Chapter VIII, "Philosophical," 226-27]

Popular entertainments make life bearable for people of all classes, implies Dickens: "fundamentally," remarks Hugh Cunningham, "the role of the circus in Hard Times is symbolic, standing for the imagination in contrast to the bombast of Bounderby and the harsh utilitarianism of Gradgrind" (22).

Above: C. S. Reinhart's realisation of the Gradgrind family's bidding Tom farewell in Sleary's circus ring in The Father Buried His Face in His Hands, And the Son Stood in His Disgraceful Grotesqueness Biting Straw (1876).

Popular Victorian recreations and entertainments for the middle-classes went far beyond puppet street-theatre, which primarily appealed to children. Aside from "rational recreations" such as waxworks, in Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, William H. Scheuerle lists among middle-class recreations and entertainments the following leisure-time activities and past-times:

••• = no material linked currently.

- •••strolling entertainers with dancing bears or dressed-up monkeys

- •••fire-eaters and jugglers

- •••Chinese shade shows such as The Woodchopper's Frolic

- Harlequin Pantomimes

- •••annual fairs such as St. Bartholomew's

- Vauxhall Gardens and Cremorne Gardens in Chelsea (closed in 1859 and 1877 respectively), and Hampstead Heath

- 340 music halls in the 1870s alone featuring dancers, acrobats, animal trainers, impersonators, and headline comics

- unlicensed "minor" theatres featuring melodrama, burletta, and farce

Related Material: Popular Entertainments and Recreations

- Music, Theatre, and Popular Entertainment

- Good Times at Greenwich Fair

- Victorian Waxworks and Charles Dickens

- London Recreations in "Scenes" from Sketches by Boz

- Private Theatres in "Scenes" from Sketches by Boz

- Vauxhall Gardens by Day in "Scenes" from Sketches by Boz

- "Steam Excursion — Pt. 1" in "Tales" from Sketches by Boz

- "Steam Excursion — Pt. 2" in "Tales" from Sketches by Boz

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Part Two: Dickens and His Principal Illustrator. 4. Hablot Browne." (Part 1). Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio U. P., 1980. 59-80.

Cunningham, Hugh "Amusements and Recreation"

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, & The Mystery of Edwin Drood.The American Household Edition. Illustrated by C. S. Reinhart. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1876. 121-228.

_______. "Greenwich Fair." Chapter 12 in Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz, George Cattermole, Samuel Williams, and Daniel Maclise. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1840.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Thomas Worth. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1872. VI.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. XII.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 viols. London: Educational Book, 1910. V.

Gold, David L. "Ghost Meanings Created by Dictionaries: The Case of Dickens's use of the Word theatricals." Dickens Quarterly 37, 3 (September 2020): 238-48.

Hall, Stephanie. "Punch & Judy in America: Lecture and Oral History with Mark Walker." Library of Congress. 5 November 2019. Web. 2 June 2020.

_______. "Puppets: A Story of Magical Actors." Folklife Today, March 16, 2018. Web. 2 June 2020.

Hartnoll, Phyllis. "Punch and Judy." The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1972. 433-34.

Home, Lewis. "The Old Curiosity Shop and the Limits of Melodrama." Dalhousie Review, Vol. 72, No. 4 (1997): 494-507.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Mayhew, Henry. "Punch's Showmen" and "Our Street Folk. 1. Street Exhibitions, Punch." London Labour and the London Poor, Volume III. Griffen, Bohn, and Co., 1861 (volume III was part of the original 1851 set). [Available from Hathi Trust. See page 61 of the digital version for a discussion and script of Punch and Judy street puppetry.]

Scheuerle, William H. "Amusements and Recreation: Middle Class." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. 17-19.

Schlicke, Paul. "Theatres and Theatricality." Oxford Readers' Companion to Dickens, ed. Paul Schlicke. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. 559-64.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 3, "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock and Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 51-85.

Created 10 October 2020