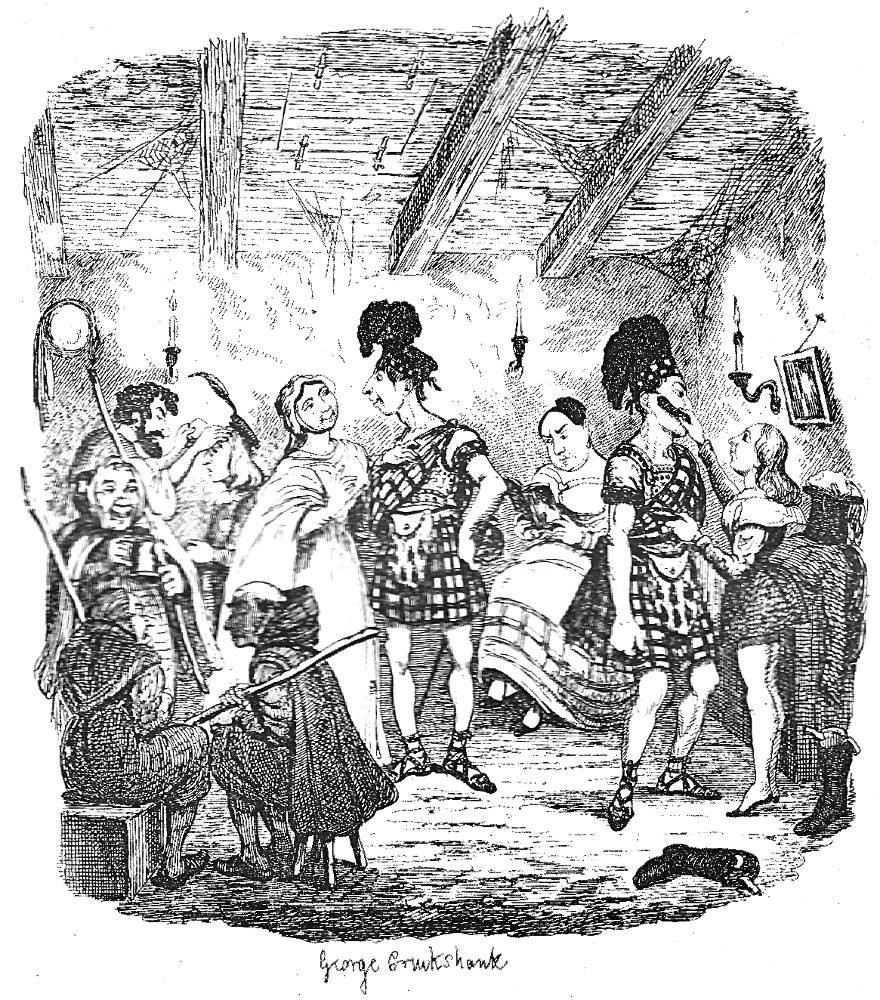

Vauxhall Gardens by Day (full-page illustration) by George Cruikshank. Copper-plate engraving (1836) and steel-engraving (1839). Original dimensions: 12.6 cm high x 8 cm wide (4 ⅞ by 3 ⅛ inches), facing p. 93; dimensions of the revised engraving 12.8 x 9.5 cm (5 by 3 ¾ inches), vignetted, facing page 93. Cruikshank's original illustration for the 1836 Second Series of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, fourteenth chapter, duodecimo, occurs at the mid-point of the chapter. First published by John Macrone, St. James's Square, London. The chief difference between the 1836 and 1839 engravings lies in the size, composition, and sharpness of the images in the audience below the stage. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: A Comic Opera Performance at Vauxhall

That the ——— but at this moment the bell rung; the people scampered away, pell-mell, to the spot from whence the sound proceeded; and we, from the mere force of habit, found ourself running among the first, as if for very life.

It was for the concert in the orchestra. A small party of dismal men in cocked hats were "executing" the overture to Tancredi, and a numerous assemblage of ladies and gentlemen, with their families, had rushed from their half-emptied stout mugs in the supper boxes, and crowded to the spot. Intense was the low murmur of admiration when a particularly small gentleman, in a dress coat, led on a particularly tall lady in a blue sarcenet pelisse and bonnet of the same, ornamented with large white feathers, and forthwith commenced a plaintive duet.

We knew the small gentleman well; we had seen a lithographed semblance of him, on many a piece of music, with his mouth wide open as if in the act of singing; a wine-glass in his hand; and a table with two decanters and four pine-apples on it in the background. The tall lady, too, we had gazed on, lost in raptures of admiration, many and many a time — how different people do look by daylight, and without punch, to be sure! It was a beautiful duet: first the small gentleman asked a question, and then the tall lady answered it; then the small gentleman and the tall lady sang together most melodiously; then the small gentleman went through a little piece of vehemence by himself, and got very tenor indeed, in the excitement of his feelings, to which the tall lady responded in a similar manner; then the small gentleman had a shake or two, after which the tall lady had the same, and then they both merged imperceptibly into the original air: and the band wound themselves up to a pitch of fury, and the small gentleman handed the tall lady out, and the applause was rapturous.

The comic singer, however, was the especial favourite; we really thought that a gentleman, with his dinner in a pocket-handkerchief, who stood near us, would have fainted with excess of joy. A marvellously facetious gentleman that comic singer is; his distinguishing characteristics are, a wig approaching to the flaxen, and an aged countenance, and he bears the name of one of the English counties, if we recollect right. He sang a very good song about the seven ages, the first half-hour of which afforded the assembly the purest delight; of the rest we can make no report, as we did not stay to hear any more. ["Scenes," Chapter 14, "Vauxhall Gardens by Day," pp. 94-95 in the 1839 volume; pp. 215-217 in the 1836 edition]

Commentary: Popular Entertainments in the Gardens

Although Dickens introduces the sketch by denigrating the notion of opening the famous Vauxhall Gardens entertainment park for daytime functions (which necessarily will not have the mysterious ambience of evening performances), the Cruikshank illustration directs the reader's attention to the heart of the essay, not the hot-air balloon race, but the operatic concert, featuring to begin with the overture from Tancredi, a musical composition by Rossini based on Torquato Tasso's sixteenth-century epic poem Jerusalem Delivered, via Voltaire's 1759 play Tancrède. Previously, Sir Walter Scott had employed Tancred as an historical character in his recreation of the First Crusade in Count Raymond of Paris (1832), his second-to-last novel. Subsequently, the novelist-turned-politician Benjamin Disraeli transformed the story into a prose fiction in 1847, Tancred, or, The New Crusade. The Romantic overture should stir feelings of grandeur and awe in the auditors to prepare them for the heroic elements of passion, war, betrayal, loyalty, heart-break, loss and honour, involved in the romantic triangle between the epic hero, the pagan warrior-maiden Clorinda, and the Princess Erminia of Antioch. (The Italian opera was first performed in Venice at the Teatro La Fenice in February, 1813.) However, young Charles Dickens, the observant reporter of the mundane made extraordinary, is far more interested in the character comedy afforded by the singers than he is by the musical setting, finding a Mutt-and-Jeff humour in the contrasting appearances soloists. The "small gentleman in a dress coat" and the "tall lady" in a white-feathered bonnet do an expostulation-and-reply duet with a "vehemence" matched by the "fury" of the accompanying orchestra, terms that suggest Dickens's response to the tempestuous nature of Romantic music, but which are not characteristic of the somewhat wooden Cruikshank scene that initiates the reader into the daytime concert at Vauxhall. The audience in Cruikshank's plate in their respectable topcoats, silk hats, printed shawls, and decorated bonnets seem to be a more respectable lot than the stampeding assemblage who have "rushed from their half-emptied stout mugs in the supper boxes, and crowded to the spot" to hear the concert. For a further discussion of the British taste for foreign opera, see the reception of Rossini's music at Covent Garden in 1829 from Derek Scott's The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour (2nd edition, 2001). For his part, Dickens appeared to have enjoyed the "native" product — the comic song out of pantomime — much more than the Rossini overture.

Vauxhall Gardens, 1816 through 1859

From the mid-seventeenth through the mid-nineteenth century Vauxhall Gardens (originally, New Spring Gardens) offered Londoners of the middle and upper classes lavish buffets, drink, music, and fireworks in a park-like setting. In 1785, when the site was re-named Vauxhall Gardens, a modest admission price was imposed. Originally, Vauxhall on the south bank of the Thames at Kennington was accessible for Londoners only by ferry, but the completion of the Vauxhall Bridge in 1816 opened the gardens up to a host of new potential customers (it is mentioned in the sketch entitled "The River," as well as in the Christmas story "Somebody's Luggage," and the late novel Our Mutual Friend).

Although its many walks and pathways were ideally suited for romantic assignations, the enormous crowds were attracted by an array of spectacular entertainments, including tightrope walkers, hot-air balloon ascents, classical music concerts, and evening fireworks provided entertainment in the lamp-lit grounds. On 8 June 1817, the Gardens even staged a large-scale re-enactment of Battle of Waterloo, with 1,000 soldiers enacting the roles of the French and British armies, to mark the first anniversary of that momentous event. Changing tastes and a greater range of entertainment options, however, led to Vauxhall's decline. Although it closed in 1840 after its owners suffered bankruptcy, it re-opened in 1841, only to suffer permanent closure in 1859. 25 July was "Positively The Last Night Forever," after a season of just six nights from 18 July; demolition began the next day, and its architectural ornaments were placed on sale a month later.

These are the thoughts of a German Prince (Herman Ludwig Pückler-Muskau) about the gardens after a visit in 1827 to see another re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo on 13 June, staged by Charles Farley of Covent Garden, resulting in an income of £2,203 for the night:

Yesterday evening I went for the first time to Vauxhall, a public garden in the style of Tivoli at Paris, but on a far grander and more brilliant scale. The illumination with thousands of lamps of the most dazzlingcolours is uncommonly splendid. Especially beautiful were large bouquets of flowers hung in the trees, formed of red, blue, yellow, and violet lamps, and the leaves and stalks of green; there were also chandeliers of a gay Turkish sort of pattern of various hues, and a temple for the music, surmounted with the royal arms and crest. Several triumphal arches were not of wood, but of cast-iron, of light transparent patterns, infinitely more elegant, and quite as rich as the former. Beyond this the gardens extended with all their variety and their exhibitions, the most remarkable of which was the battle of Waterloo. [Jane Austen's World]

"Vauxhall Gardens by Day" was originally published as "Sketches by Boz, New Series No. 4" in the Morning Chronicle on 26 October 1836. In "Scenes," six of the sketches involve recreation and entertainment for the rising middle classes: Ch. 9, "London Recreations," Ch. 10, "The River," Ch. 11, "Astley's," Ch. 12, "Greenwich Fair," Ch. 13, "Private Theatres," and the culmination of this strand, Ch. 14, "Vauxhall Gardens by Day." Cruikshank, however, has provided illustrations for just four of these pieces, so that London Recreations, Greenwich Fair, and Private Theatres complement the operatic entertainment presented in Vauxhall Gardens by Day. Whereas in the previous entertainment illustrations Cruikshank had focussed on the middle-class crowds (mostly male), in London Recreations and Greenwich Fair, in the present illustration and Private Theatres the illustrator is much more concerned with the performers, the Green Room casualness of the actors in Macbeth contrasting the formal performance of the dozen (entirely male) musicians playing the Rossini overture for the audience in the bottom margin, reduced to mere dozen hats. In contrast to the wooden, unimaginatively attired musicians, Cruikshank's physical setting of the performance space is delightfully elaborated, with a seashell motif above supported by tree trunks and columns formed of military drums and gigantic lyres.The other illustration that probably deals with Vauxhall Gardens by Day is the hot-air balloon ascent pictured in the Chapman and Hall monthly wrapper for the serialisation of the collected Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (November 1837 though June 1839).

The Three Other "Entertainment" Illustrations by Cruikshank

Left: Cruikshank's far more animated and engaging musical entertainment, Greenwich Fair. Centre: Cruikshank's view of the leisured middle classes ar a Sunday tea-garden, London Recreations. Right: Cruikshank's depiction of the amateur actors backstage, Private Theatres. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

See also "The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850:

- The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850

- The Development of Leisure in Britain after 1850

- Technology and Leisure in Britain after 1850

Scanned image, image correction, formatting, and caption by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cunningham, Peter. "Seven Dials." Hand-Book of London. London: J. Murray, 1850. Pp. 445.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Vauxhall-Gardens by Day." Sketches by Boz. Second series. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: John Macrone, 1836. Pp. 211-224.

Dickens, Charles. "Vauxhall Gardens by Day," Chapter 14 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 93-97.

Dickens, Charles. "Vauxhall Gardens by Day," Chapter 14 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 59-62. Vol. XIII.

Dickens, Charles. "Vauxhall Gardens by Day," Chapter 14 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 119-124.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Jackson, Lee. "Victorian London — Entertainment and Recreation — Gardens — Tea Gardens." The Dictionary of Victorian London. New Haven: Yale U. P., 2014. Web. Accessed 27 April 2017.

Scott, Derek B. The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour. 2nd ed. Aldershot, Hampshire; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2001.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Pückler-Muskau, Hermann Ludwig, Fürst von, Prinz. Tour in England, Ireland, and France: in the years 1826, 1827, 1828 and 1829; with remarks on the manners and customs of the inhabitants, and anecdotes of distinguished public characters. In a series of letters. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea, & Blanchard, 1833.

Vauxhall Gardens 1661-1859, Full Chronology. Web. Accessed 30 April 2017.

"Vauxhall Gardens." Jane Austen's World. Posted March 1, 2009 by Vic. Web. Accessed 27 April 2017. in Jane Austen's World.

Created 28 April 2017 Last updated 17 May 2023