Man lives forward and understands backward. — Kierkegaard

The lasting element in thinking is the way. And ways of thinking hold within them that mysterious quality that we can walk them forward and backward, and that indeed only the way back will lead us forward. — Heidegger

Throughout the eighteen-forties, Dickens tried to come to terms with the past — with revolution, romanticism, pre-iniustrialism, his own life.1 In June 1845 while staying in Genoa he told Forster for the first time about his early theatrical ambitions (Letters I, 680-81). Seventeen months later he sent the nitial chapter of Dombey and Son III to Forster, explainng that Mrs. Pipchin's "establishment ... is from the life, and I was there — I don't suppose I was eight years old; but remember it all as well, and certainly understood it as veil, as 1 do now."3 Mrs. Pipchin, née Roylance in the lumber plans,4 has been variously identified as the "reduced old lady, long known" to the family, who took the twelve-year-old Dickens in while his father was incarcerited in the Marshalsea, later accommodating the rest of the family too (Forster, 1, ii, 27 and 33), and as "an old lodging-house keeper in an English watering place" (probably Southsea) to which the family travelled during the summer of 1814, when Dickens' brother Alfred was born and died (Horsman, p. xxv). Neither of these events squares with the notion that Dickens was "eight years old." [269/270] Nor is it at all clear, from other evidence, that Dickens "understood it," whatever "it" is, then, though it may be true that he "understood it [then] as well" as he did in 1846.

For Dickens hadn't come to any full understanding of his past and of its complex relation to his present. Some lessons seemed obvious: "We should be devilish sharp in what we do to children," he continued to Forster. However limited their perspective and comprehension, children know intuitively, feel acutely, and perceive selectively. Through his children and memories of his own past Dickens had been getting in touch with those responses for some time: "I thought of that passage in my small life, at Geneva," he added. "Shall I leave you my life in MS when I die? There are some things in it that would touch you very much, and that might go on the same shelf with the first volume of Holcroft's [Memoirs]."

Alan Horsman, in his "Introduction" to the Clarendon Dombey, concludes that "there is then a close relationship between the [autobiographical] fragment and Dombey and Son, in the time of gestation and composition as well as in part of the content, and, behind both of these, though whether as cause or consequence is uncertain, in the increasing adoption of the child's standpoint as the early part of the novel proceeds."7 What Paul understands — which according to Dickens' testimony reflects what he himself understands of this composite past — is a product of the way Paul sees others, sees himself, and sees his possibilities. Mrs. Pipchin is an "ogress" — "a marvellous ill-favoured, illconditioned old lady, of a stooping figure, with a mottled face, like bad marble, a hook nose, and hard grey eye, that looked as if it might have been hammered at on an anvil without sustaining any injury" — and a "child-queller," whose secret for success as a child-manager "was, to give them everything that they didn't like, and nothing that they did" (ch. viii, p. 100). In short, she takes her place in a Dickensian genealogy of life-denying mothers: she still wears black bombazine mourning as the relict of a husband who broke his heart, not in romance, but over an unsuccessful speculation "in pumping water out of the Peruvian Mines" (ch. viii, p. 99). These non-nurturing parents go back in Dickens' fiction at least as far as Oliver's foster-mother, the ominously named Mrs. Mann.10 Mrs. Pipchin's indoor garden provides a fair sample of her capacity to foster fertile, vital, pleasant life: the epitome of violent vegetation, it contains writhing hairy cactuses, creeping sticky-leaved vegetables, and spidery pot plants, "in which Mrs. Pipchin's dwelling was uncommonly prolific, though perhaps it challenged competition still more proudly, in the season, in point of earwigs" (ch. viii, p. 101.).

Paul, by contrast, is diminutive, wise beyond his years, physically impotent, but spiritually incorruptible. He confounds his father with a catechism on money, and Mrs. Pipchin with similar innocent questions. The result of the confrontation of knowing but dependent boy and ogress in her Castle is a kind of stand-off, a truce, a conversion of the potentially fatal opposition into complicit stasis; each develops a "grotesque attraction" (ch. viii, p. 104) for the other, and they often sit staring at one another before the fire.

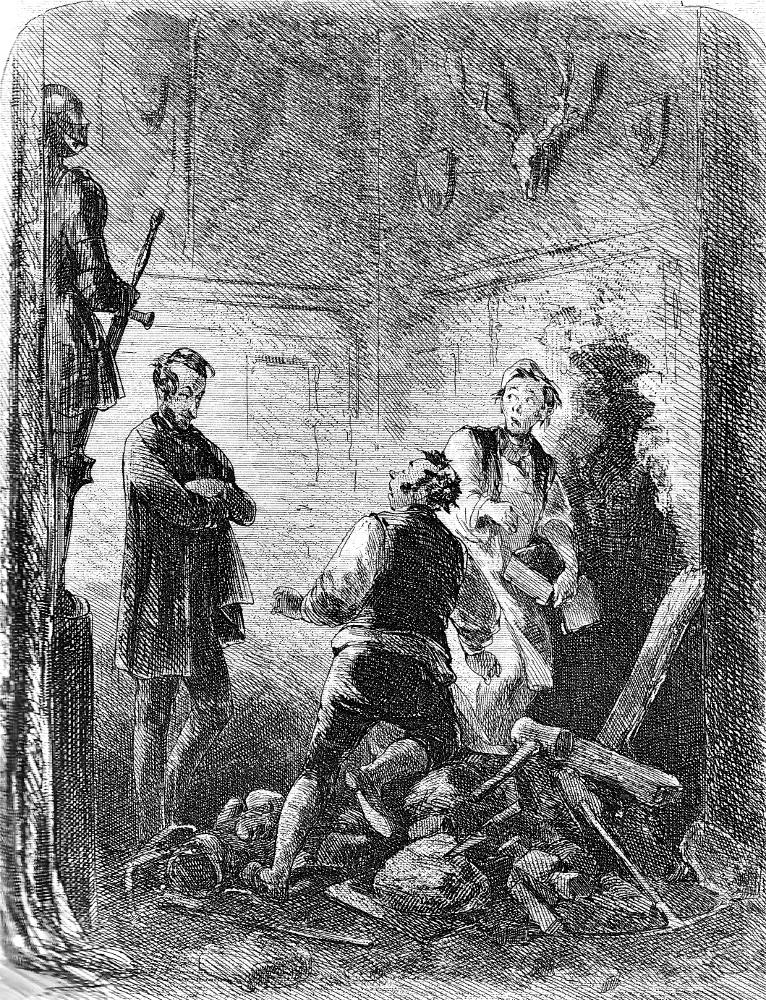

When Dickens saw the plate depicting this scene, on which he hoped Browne would expend "a little extra care,"13 he blew up:

I am really distressed by the illustration of Mrs. Pipchin and Paul. It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark. Good Heaven! in the commonest and most literal construction of the text, it is all wrong. She is described as an old lady, and Paul's "miniature armchair" is mentioned more than once. He ought to be sitting in a little armchair down in a corner of the fireplace, staring up at her. I can't say what pain and vexation it is to be so utterly misrepresented. I would cheerfully have given a hundred pounds to have kept this illustration out of the book. He never could have got that idea of Mrs. Pipchin if he had attended to the text. Indeed I think he does better without the text; for then the notion is made easy to him in short description, and he can't help taking it in. [Forster, VI, ii, 478]

Paul and Miss Pipchin: the preparatory drawing and finished plate by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

Yet the original design and the plate both seem quite compatible with the text: Mrs. Pipchin is hardly young, Paul is sitting in a kind of small high chair looking up at her, though the text insists only that he looks "at" her, the cactuses are faithfully and spikily present, and together with the cat the three familiars interact in Browne's graphic presentation exactly as they do in the text: [271/272]

She would make him move his chair to her side of the fire, instead of sitting opposite; and there he would remain in a nook between Mrs. Pipchin and the fender, with all the light of his little face absorbed into her black bombazeen drapery, studying every line and wrinkle of her countenance, and peering at the hard grey eye, until Mrs. Pipchin was sometimes fain to shut it, on pretence of dozing. Mrs. Pipchin had an old black cat, who generally lay coiled upon the centre foot of the fender, purring egotistically, and winking at the fire until the contract! pupils of his eyes were like two notes of admiration. The good lady might have been — not to record it disrespectfully — a witch, and Paul and the cat her two familiars, as they all sat by the fire together. [ch. viii, pp. 104-105.]

A possible explanation for Dickens' exasperation lies in the difference in point of view.16 Chapter VIII, "Paul's further progress, growth, and character," hovers between the child's perspective and the adult's, between Paul's selective vision and spiritual incorruptibility and the narrator's more comprehensive insight, pity, and precognition that the result of the child's parental deprivation will be an early death: "Naturally delicate, perhaps, he pined and wasted after the dismissal of his nurse, and, for a long time, seemed but to wait his opportunity of gliding through their hands, and seeking his lost mother" (ch. viii, p. 91). Browne finds no way to imitate graphically this unresolved tension of perspectives: he offers instead a box stage set, the characters and props arranged according to instructions, all three poised in attitudes of brooding, the cat at the fire, Mrs. Pipchin inwardly on her own past, Paul on "every line and wrinkle of her countenance"; but there is no mediating artistic lens. Paul's consciousness is within the picture, the adult narrator's outside it.

That convergence of perspective between eight-year-old and adult which Dickens claimed for his episode inheres neither in the novel's point of view, divided between innocence and experience, nor in the plot or myth, which gift Paul with preternatural wisdom and insufficient vitality. How can the living thirty-four-year-old Dickens say he "understood" an experience metamorphosed fictionally into a unbearable and unresolvable tensions? He lies, in the Romantic way of lying, by projecting as defense another version of the wounded artist who knows through deprivation too much to survive. [272/273]

I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am. — Dickens

Theatrical avatars, inhabiting someone else's clothes and language, were one way of surviving — or even more, of becoming adequate, potent.18 But the connections between self and avatar lie in the contingent similarity or analogy; they are, beyond the choice of roles, not under the actor's control. Creating the characters as author (Dickens in the process of composition frequently acted out the roles in a mirror: writer, actor, and critic at once)19 puts more of the vital connection between life and art, self and other, in the hands of the creator. Yet at the end of Dombey Dickens opts for a past and dying world over the present and living one, and continues to image the choice as one be been mutually exclusive and destructive opposites.20 At roughly the same time (earlier if the "life in MS" was written by Dombey III, later if it was prompted by Forster's casual inquiry in "March or April of 1847" [I, ii, 23]) however, Dickens composed his autobiographical fragment concerning the blacking warehouse, which may be an account of the time immediately preceding the family's stay at Mrs. Roylance's during and after the Marshalsea incident.

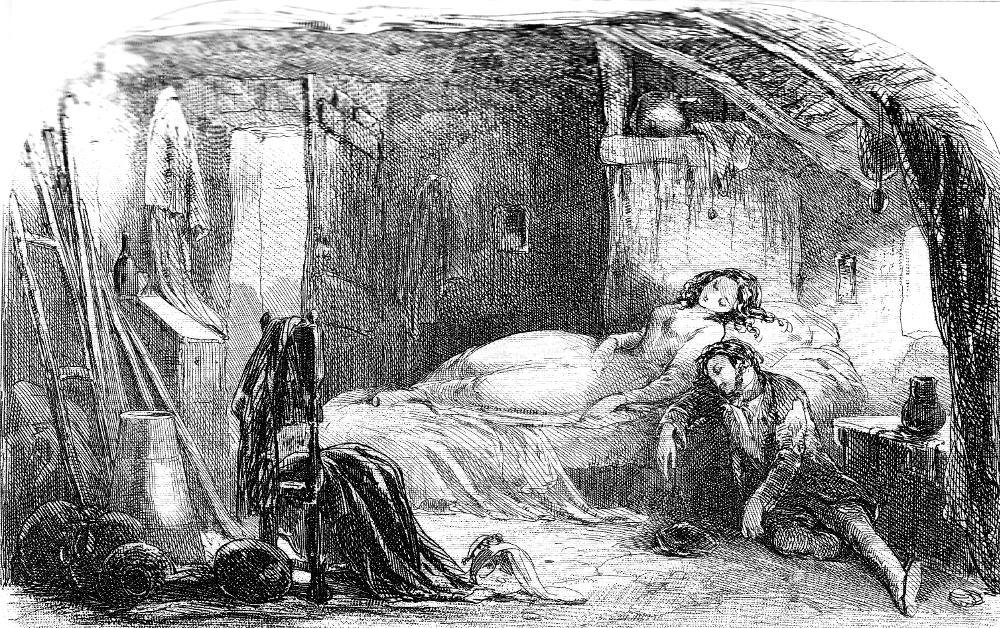

The basic difference between this fragment and the Pipchin episode is that it is written by a survivor. Whatever the facts, they must explain how it was possible to live, to endure this deprivation. In Dickens' version, the child is, if anything, more abandoned and powerless even than Paul. He is "so easily cast away"; "no one had compassion enough"; "no one made any sign." He is marooned in a "crazy, tumbledown old house . . . literally overrun with rats." Worse than Mrs. Pipchin's cactus, this environment is characterized by consuming decay. And the companions are not mistresses of a household with whom one can hold secret and equal communion, but the orphan Bob Fagin who is kind to him when he succumbs to "a bad attack of my old disorder," and Paul (Poll) Green. Kindness and sympathy in such a place take on threatening aspects by of[273/274] fering friendship and accommodation and help for unwillingly confessed weakness; hence Bob Fagin's reward: "I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist." Though not all the charity can be rejected hence Poll Sweedlepipe in Martin Chuzzlewit.23

Abandonment by others into this lower order of existence leads to abandonment by self of one's dreams for a hopeful future. "No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sunk into this companionship; compared these every day associates with those of my happier childhood; and felt my early hopes of growing up to be a learned and distin guished man, crushed in my breast." To make this sense of loss even more piercing, his sister Fanny continued at the Royal Academy of Music, pursuing a course of study that seemed to promise fame and fortune, and certainly singled her out in the present as preferred. He felt utterly neglected and hopeless, experienced shame and misery, grief and humiliation, saw all joy passing by.

Moreover, all this is done to him, by others. The child is essentially powerless to affect his fate; he is the victim of his parents and circumstances that cast him away, sink him, crush him, cut him off from parents, family, hope. His powerlessness is so great, his resources are so scanty, that he discovers his inability even to portion out his wages to last through the week, squandering on stale pastry set out at half price on trays in the confectioners' shops the pennies that should have been saved for dinner. Despite his I best efforts he seems to be slipping into the condition of another self-consuming decayed relict. Self-discipline and self-reliance cannot withstand the temptations of the city, and Charles is poised to enact once again the familiar declension from poverty to hunger, and hunger to crime, paradigmatically displayed in the life of Moll Flanders: "I know that, but for the mercy of God, I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a little vagabond."

What is missing from this account is any causal agent. It was "an evil hour" that cast him away and crushed him; though "utterly neglected and hopeless," he does not accuse his parents of that neglect. He has no assistance: "No advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from any one that I can call to mind, so help me God." But nobody to blame, either. There is not in this fragment a denunciation of the "Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order" who reduce Jo,25 nor a portrayal of the inhumane efficiency of institutional charity that supervises Oliver,26 nor an arctic Dombey, nor a fiendish Fagin. He is "so young and childish, and so little qualified — how could I be otherwise? — to undertake the whole charge of my own existence," that the world seems reversed: the child must act the man, self-sufficient, self-employed, ordering a-la-mode beef in the best dining room of Johnson's beef-house, or ale at a pub in Parliament Street (an incident afterwards transferred to David in Copperfield), drinking coffee and eating bread and butter from behind a glass that symbolically and talismanically reversed the world's language: MOOR-EEFFOC. "If I ever find myself . . .where there is such an inscription on glass, and read it backward on the wrong side MOOREEFFOC (as I often used to do then, in a dismal reverie), a shock goes through my blood."

For all its deprivations, the life had certain covert and hard-won advantages. If there is no author to one's existence, no causal agent, one can make oneself, as Dickens did, becoming extremely skilled at his task, forcing a stoic silence on the pain, establishing by his conduct and manners 'a space" between the others and himself, and creating, even in these surroundings, the persona of "the young gentleman," in imitation of his father's oratorically projected gentility. There was another kind of skill he appropriated to himself from his father, that facility with words as instruments for creating a different, better reality than the blacking warehouse or the Marshalsea. When the boy visits the prison he hears Captain Porter read the text of John Dickens' petition for permission to drink the king's health on his birthday "as if the words were something real in his mouth, and delicious to taste," while in a corner he "made out my own little character and story for every man who put his name to the sheet of paper."

But such practical skill and fantasy do not themselves [275/276] create or cancel the real world, nor make entirely adequate the lot of the abandoned child. However much one may imagine oneself to be "a child of singular abilities, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt, bodily or mentally," the reality as otherwise is exposed the moment one performs the task of tying up blacking bottles in a window before the admiring street public. And so Dickens, out of his powerful need to be lovable and loved, imagines that his father came to the window, saw him there like a figure in a play, and quarrelled with his relative James Lamert by letter, Charles serving as intermediary. There is no confirmation that the quarrel was about the window: "It was about me. It may have had some backward reference, in part, for anything I know, to my employment at the window." Dickens' release threw him into a very ambivalent frame of mind, for he had to acknowledge the end both of abandonment and self-creation: "With a relief so strange that it was like oppression, I went home."

But the story does not end with the child acknowledging his dependency again, returning to the hearth and heart of his family, and magically transforming from premature adult to fostered child. For Mrs. Dickens tried to accommodate the quarrel, to reconcile her husband to Lamert, and to restore her son to his self-creating servitude. John Dickens opposed this eminently practical, if insensitive, move, urging instead that the boy be sent to school to acquire that language which was John's real medium of being, if we are to judge from the extant texts and Mr. Micawber. Elizabeth Dickens seems to be concerned about feeding her family; John, about feeding their ambitions. Significantly, Dickens' hunger required even more of John's remedy, by this time, than of Elizabeth's.

"I do not write resentfully or angrily: for I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am: but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." It is another lie, a necessary fiction. Mrs. Dickens visited the boy often during the interval; Mr. Dickens, but seldom. The whole incident lasted a few months; but [276/277] Dickens has "no idea how long it lasted; whether for a year, or much more, or less." He makes claims for a kind of understanding of the uses of the past, "how all these things have worked together to make me what I am," but he exhibits no such understanding, no such forgiveness. The refusal to forget his mother's "warmness" (interesting ambivalence in itself, signifying in context heat but in meaning coldness) sounds like an incantation or spell not to forget, testimony that he has not forgotten, will not and can not forget, the narrowness of his rescue from a condition with which he was unable to cope. Having gone through the experience of abandonment, having come face to face with his insufficiency, Dickens then erected, and still (1847) maintains, the willed fiction of an abandoning mother. By that fiction, maintained secretly as talisman ("no word of that part of my childhood . . . has passed my lips to any human being"), Charles, boy and man, can keep the rewards of that dearly bought knowledge: a kind of masculine independence involving self-sufficiency, skill in work, sympathy with the oppressed and abandoned, and creation through imagination and language. He also fixes for himself a way of thinking about women that makes them either undependable as sources of nurture and protection, or idealized as the source of all the adequacies which the child perceives himself to lack.

In The Haunted Man (1848) Dickens claims that he taught "that bad and good are inextricably linked in remembrance, and that you could not choose the enjoyment of recollecting only the good. To have all the best of it you must remember the worst also."27 Forster goes farther, appending a moral that is at once psychologically acute and utterly inapplicable to Dickens himself: "The old proverb does not tell you to forget that you may forgive, but to forgive that you may forget. It is forgiveness of wrong, for forgetfulness of the evil that was in it; such as poor old Lear begged of Cordelia" (VI, iv, 509) But Dickens can not and will not forget or forgive, because complexly the recollection and preservation of the wrong done to him are the secret sources of his being. Yet he really does not understand that connection. The autobiographical [277/278] fragment is incomplete, truncated; it bears no connection to the future life of the child or the present life of the adult; it projects no telos out of suffering that converts misery into accomplishment, trauma into understanding. The survivor can not say, will not admit, why he has survived.

David Copperfield becomes a third version of the abandoned child, another try at connecting past to present and writing oneself into adequacy.

Do you care to know that I was a great writer at 8 years old or so — was an actor and a speaker from a baby — and worked many childish experiences and many young struggles, into Copperfield? . — Dickens

It would be the greatest mistake to imagine anything like a complete identity of the fictitious novelist, with the real one, beyond the Hungerford scenes; or to suppose that the youth, who then received his first harsh schooling in life, came out of it as little harmed or hardened as David did. — Forster

Once entertained, the psychic material of Dickens' past would not go away. "Penetrated with the grief and humiliation" of the Hungerford stairs blacking warehouse days, he could not shake their memory and power, and "even now, famous and caressed and happy" — three adjectives that pregnantly convey the contrast between past and present — "I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time of my life" (Forster, I, ii, 26). Every word of his confession reveals the destructive cost to the self of this nodal past: "penetrated," "forget ... I have . . . wife and children," "forget . . . even that I am a man," "wander," "desolately": the net result is an image of un-manning, of stripping away the power and personal integrity of adulthood to reveal again the vulnerable, lonely, dependent, lost, and despairing child.

But — and it is a momentous but — Dickens the writer can deal at arm's length, or more accurately at word's length, with these contradictory images of self. He can retrace, seeking for further connection and integration, the path of [278/279] his soul, traversing, as Hegel put it, the series of its own stages of embodiment, like stages appointed for it by its own nature. He had already done so, in a highly fictionalized and displaced account, with Scrooge;30 he had moved closer to the past with Paul Dombey, closer still with the autobiographical fragment; and he had at least set up a therapeutic model in the moral of The Haunted Man.

Events conspired to help him further. The enormous financial success of Dombey permitted Dickens, for the first time in his career, to choose the timing and subject of his next serial. Immersed in this quest to comprehend how all things worked to make him what he was, he continued the search in the book that became, significantly enough, his "favourite child." And once again, as so often in Dickens' life, John Forster made a crucial suggestion. Why not try a first person point of view? Dickens had attempted it once before, with Master Humphrey's "Personal Adventures," and found the multiple confinements so restrictive that he abandoned the fiction at the end of the third chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop with the clumsiest artistic ruthlessness of his entire life.31 Now Forster's idea offered a perfect way to deal with the ambivalences of Dickens' understanding and perspective. The autobiography of a fictional character permitted him to establish a cordon sanitaire between the "I" of David and the "I" of Dickens; and a novel of the personal history and experiences of a child growing up could incorporate both the child's perceptions and the adult's. The divisions of Dombey and the autobiographical fragment were at a stroke resolved.

The wrapper (cover for monthly parts) that Phiz created for Dombey and Son

"Deepest despondency, as usual, in commencing, besets me," Dickens told Forster as he wrestled with selecting a name for his new work.32 Whereas ordinary novels can wait to be christened until they are born, serial publications are delivered piecemeal, name first so that an advertising campaign can commence; then the "general drift" so that the illustrator can design a wrapper; then some number plans so that the "general drift" is spaced out across the quite exact number of pages, lines, and words of the whole; then the opening chapters; and only two years or so later, some nineteen [279/280] months after publication of the first installment, do the conclusion and the preface get written. Naming the unborn child thus becomes unusually difficult and important; to a large extent the entire subsequent text is generated in idea and language from the title.

The first versions promised a return to the humorous Dickens of Pickwick, though they were open to the "difficulty of being 'too comic, my boy.' " Mag's Diversions was glossed as "Being the personal history of / MR. THOMAS MAG THE YOUNGER, / Of Blunderstone House." Then Thomas became David, and "personal history" expanded to "Personal History, Adventures, Experience, and Observation." Suddenly, via nickname, Mag underwent a sex change, emerging almost unrecognized as Aunt Betsey: "Mr. David Copperfield the Younger and his great-aunt Margaret." That metamorphosis is replicated in the novel in I David's repeated transformation into Betsey Trotwood Copperfield.

"You will see that [I have given up] Mag altogether, and refer exclusively to one name — that which I last sent you," Dickens wrote to Forster on 26 February 1849. That "one name" was David Copperfield, who as "the Younger" possesses in many ways the potential to grow into a duplicate of his unfortunate father, David Copperfield the Elder, whose accomplishments during his brief life are all too well expressed in the name of his abode, Blunderstone House, Lodge, or Rookery (without rooks, of course). The next set of six titles sent with this letter establishes a second, and equally important, fiction. Three of them explicitly denote the book as the record of a completed life, and the other three titles, by implication or Dickens' suggested modifications, seem to share that notion too. What sort of precedent existed for novels that end not with marriage and happyever-aftering, but with death? Newgate novels: the outgrowth of confession, the picaresque, eighteenth-century of sensationalist broadside publications, and nineteenth-century concern (Godwin, Bulwer, Dickens) with the origin of evil.33 The third of Dickens' new batch of provisional titles makes the association between the orphaned child and the a [280/281] condemned man plain: "The Last Living Speech and Confession of David Copperfield, Junior, of Blunderstone Lodge, who was never executed at the Old Bailey."

Dickens piles reversal on reversal. A comic Newgate novel becomes possible if the protagonist, like Oliver and unlike Fagin, is "never executed." The life forms a comic whole, in Northrop Frye's terms. The patterns are complete only at the moment of death, yet an autobiography cannot be composed in an instant — the understanding obtained, the events selected, their significance ascribed, and the just conclusions reached, during the death rattle. Further, there is something odd about publishing a personal history, something about making the private public that implies dishonesty, deliberate shaping, even fraud. The pattern might be imposed on, not discovered in, the events. So the subtitles insist that the novel is "his personal history found among his papers," or "his personal history left as a legacy," or that "he never meant [the papers] to be published on any account."

The biggest reversal of all, one that accounts for these others, took place when Dickens settled on Copperfield: "I doubt whether I could, on the whole, get a better name." For, as Forster pointed out to a "much startled" auditor, David's initials are Dickens' in reverse. Upon learning this odd fact, Dickens "protested it was just in keeping with the fates and chances which were always befalling him. 'Why else,' he said, 'should I so obstinately have kept to that name when once it turned up?'" Why else, indeed. It was not any abstract fate or chance. David the Younger (as child) is the reverse of Dickens the writer as adult, and so is the experience of Dickens as child playing adult epitomized by the reverse letters MOOR-EEFFOC. Projection, compensation, displacement, splitting or doubling, reverse psychology - call it what you will,35 the fact remains that Dickens found in these inversions, reversals, and splits into doubled characters, sexes, and perspectives, these reformulations of past experience that affect everything from the alphabet and language to the fiction of a completed life written from incompletion, an artistically and psychologically satisfying [281/282] way of resolving tensions, of creating a new child that would incorporate the old one but convert defeat into victory.

David is not Dickens. Forster shrewdly anticipates much twentieth-century criticism on autobiographical transformation when he warns that it would be a mistake to suppose Dickens came out of his "first harsh schooling in life . . . as little harmed or hardened as David did." And he identifies the fundamental difference between the two, a difference inherent in the radical discontinuity between language and life: "The language of the fiction reflects only faintly the narrative of the actual fact (VI, vii, 553). Forster understands that the fiction is shaped by generic expectations and by the tradition, that the effort to communicate involves transmuting the individual and transient into the general and permanent through myth embedded in language and structure. He perceives that, and how, David Copperfield finds his place in his own, not Dickens' story:

The character of the hero of the novel finds indeed his right place in the story he is supposed to tell, rather by unhkeness than by likeness to Dickens, even where intentional resemblance might seem to be prominent. Take autobiography as a design to show that any man's life may be as a mirror of existence to all men, and the individual career becomes altogether secondary to the variety of expe- riences received and rendered back in it. [VI, vii, 553-54]

Forster's comment goes to the heart of another organizing principle that Dickens discovered in his naming of the novel. In the subtitles he expands "personal history" to include "Adventures, Experience, and Observation" for the wrapper design, but conflates the paired terms to "Personal History and Experience" for the text headings. As Forster observes, the "individual career" ("history") is "altogether secondary" to the "variety of experiences":

the facts, in autobiography, less important than the way they are taken, the significance they are accorded.38 Thus "Personal History and Experience" divides the narrative from the general stream of language and event through "personal," and further divides fact from feeling, event from signification, objective from subjective, external from internal. The adult who as child had experienced sequentially [282/283] through time and simultaneously in any instant his history and his experience divides the two up in his retrospective fiction: such and such happened, such and such is the way I felt. That division allows events to be seen in at least four different lights: first, by the child David Copperfield the Younger, who organizes and interprets experience in terms of hopeful forward telea, fairy-tales about future becoming;39 second (and infrequently), by the adult David Copperfield the Elder, who never outgrows his foolish and impractical hopes", third, by the adult David Copperfield the Younger, who after replicating his father's errors grows further, and by organizing and interpreting experience in a different way, by looking backward, discovers in Switzerland an emerging telos concealed in his past life that permits him to compose a fiction making his beginnings concurrent with his ends; and fourth, by Charles Dickens the author, whose understanding of his life and his work emerges in the writing.40 The child and child-like man, innocent, imagine the future; the adult writers, experienced, interpret the past. The same event may be seen as having alternate significations: Emily's dream of becoming a lady; Steerforth asleep, lying with his haad upon his arm; David Doady's child bride.

By separating "History" from "Experience" Dickens obtains a double principle of selectivity, one that is both psychological and thematic. He can recount those passages in David's life (and his own) which explain the present of the writer, not merely supply an undifferentiated history. And these incidents will be not only selected but also narrated in terms of their significance as understood by the crossed rays of the child's intelligence and the narrator's. Hence the extraordinary interplay of tones, of precise focus and blur of feeling, of incidents followed by the haze of "Retrospect," and of the poignant tension between the child's hopes and adult knowledge.

Victorian novels are about ends: whatever sense of direction or purpose can be salvaged from experience. — Alexander Welsh [283/284]

So far, so good. Dickens imaginatively resolved all the subsidiary problems by the decision to write a first person novel about the history and experience of someone else. Yet the major problem remained, to be worked out in the writing: how to understand his own past well enough to connect the child-figure to the adult, David Copperfield the Younger to David Copperfield the writer. Whether Dickens consciously intended it to or not, David Copperfield dramatizes and enacts the writer's coming into adequacy through writing. Not only does the character become an adequate writer, but also he becomes a hero, if at all, through the writing of his life.

But Dickens, possessing no sure conclusion at the beginning of his story, aware in his own life of no certain telos connecting past to present, starts the novel with perhaps the most open beginning in all literature, the declarative sentence least constitutive of self-creation in any firstperson work: "Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show."41 At the beginning, meaning is radically indeterminate.

It is so for many reasons. Because the personal history, at the moment of birth, is unlived, only potential. But since it is only a convention of the fiction that the life is yet to be lived, it being narrated after all by the survivor, the sentence takes on meaning at a deeper level. Beyond the convention that the future is open is the fact that its significance remains undetermined even after living. What does the experience of that history amount to? Is David the hero, or someone else? Is he the master of his fate and captain of his soul, or product of the forces that shape his being and his options? Has he acted or been acted upon?

There is yet a third level of indeterminacy hiding behind the other two. For the decision about David's place as hero rests not with the narrator who identifies an emerging telos, but with the book itself: "these pages must show." Does heroism reside in the character acting, in the narrator evaluating, or in the book as art? Dickens seems to open the door not only to Conrad's baffling question whether heroism [284/285] depends on the doer (stoic or warrior) or on the interpreter, but even further, to unanswerable, nearly imponderable, speculations. David Copperfield as text defines David Copperfield as hero heuristically, but in a mysterious and disappointing way it defines neither David Copperfield nor heroism. The questions and answers remain teasingly and obstinately posed between the covers of the book.

The hermeneutic character of literature42 is not addressed directly, however, until the novel's conclusion, when Dickens closes David's story and life with the extinguishing of the writer's lamp, transferring light and life from the fiction of life ("realities . . . melting . . . like the shadows") to the reality of the Christian soul: "Oh Agnes, oh my soul, so may thy face be by me when I close my life indeed; so may I, when realities are melting from me like the shadows which I now dismiss, still find thee near me, pointing upward!" The more immediate problem to work out is the secondary level of David's fate, whether, and in what sense, he is a hero.

Every portent is ambiguous. He is born at midnight, poised between Friday's and Saturday's child, unlucky and privileged, with a caul to protect him from shipwreck which may be the universal lot of man; posthumous, virtually motherless, hastened into the world by a bad fairy godmother who would deny his sexuality and identity from the start; nursed by a mother-substitute also named Clara who is comic but socially ineffective; threatened by a virile hairy stepfather associated with a biting dog (no friendly crocodile), whose existence seems purposed to punish the child for seeking physical and spiritual nourishment from a true parent. The caul is put up for sale but not sold, then ten years later raffled to an old lady whose proudest boast was "that she never had been on the water in her life, except upon a bridge"; and it is a remarkable fact that she died at ninety-two in her bed, and was never drowned.

Fact and signification remain perplexingly dissociated, while the imagination longs to bring them into concord. The old lady attacks "the impiety of mariners and others, [285/286] who had the presumption to go 'meandering' about the world," saying, no matter what objections were raised to her prejudice, "Let us have no meandering" (Chapter I, p. 2). Yet most, David included, are not able to live without travelling, cannot avoid risking their lives in journeys. Travel across water has been the archetype of the soul's progress from Biblical times to Jung. The narrator of David Copperfield immediately (and persistently) connects the journey across water literally and spiritually through life to the journey through language: "Not to meander myself, at present, I will go back to my birth."

Life and language may be coterminous and congruent; indeed life in some senses may not exist without the language of its experiencing. Thus David's life is the product of his fiction as Charles' is of his, in ways that are almost too complex and redundant to discriminate. The writer learns to make his reality through language, and learns that language makes, constitutes, possibly is reality. He becomes adequate through fictions of his adequacy; he becomes his own self-creating father and son, defining heroism to suit his condition.

One thing novelist and novel do is to examine the inadequacy of the fairy-tale telea David projects as a child: virtually every one of the hopeful futures dreamed by the characters — David, Emily, Ham, Peggotty, Steerforth, Rosa, the Heeps, the Wickfields — proves in time illusory, vain. The uneducated children turn out to be blind, conceited, unprepared, undisciplined.44 Yet exiled in Switzerland the writer David discovers in the disappointment of expectations, through Agnes' letters, an emergent telos that makes him what he is and the book what it is: "As the endurance of my childish days had done its part to make me what I was, so greater calamities would nerve me on, to be yet better than I was; and so, as they had taught me, would I teach others" (ch. lviii, p. 815). He resolves to resume his pen, and working patiently and hard he composes "a Story, with a purpose growing, not remotely, out of my experience" (ch. lviii, p. 816).

Insofar as that fiction is David Copperfield, it is important to note that the novel incorporates Dickens' autobiographical [286/287] fragment, which is now ultimately perceived in the structure is one of many times when the fictional protagonist re-cn tes himself in isolation, "abandoned and despairing, make[s] another Beginning,"47 and discovers in that re-creation a power that renews life in those moments when he is afflicted by "a hopeless consciousness of all that I had lost — love, friendship, ii crest; of all that had been shattered my first trust, my first affection, the whole airy castle of my life; of all that remained — a ruined blank and waste, lying wide around me, unbroken, to the dark horizon" (ch.lviii, p. 813). By joining the autobiographical fragment to other fragments, Dickens establishes the radical continuity between devitalized child and surviving adult, failure and success, wish and fulfillment.

Finally, Dickens can confront apocalypse: Emily's ruin, Steerforth's and Ham's deaths, Dora's fatal incompetence, his own shipwrecked hope. Out of that confrontation he develops his thesis about identity, the alternate telos, and the novel. That he and David together connect their ends with their beginnings triumphantly testifies to Dickens' understanding, at last, how all these things have worked together. In his search, his journey, however, he is sustained by a faith (a "caul"), a belief that in essence he has never ceased to be a sponsored child, the son of God. It was "the mercy of God" that preserved Dickens from becoming a thief; and he shares with Paul Dombey that radical transvaluation of values which is the Christian's consolation. The various inadequate women, from Clara Copperfield to Dora, who seem to preside over David's fate, are eventually replaced by Agnes and the recognition that she has supplied the real and lasting protection and encouragement. And what she stands for, as we have seen, becomes an extra-literary confirmation of David's identity (Miller 157).

Thus, in his own act of writing, David/Dickens himself creates the world of his desire and discovers for himself and us its design and meaning. He unfolds the hero from his indeterminacy, discloses the writer in the name. The self-creating fantasies of the child become the self-fulfilling fictions of the adult, who in remaking his own child not in [287/288] his image becomes a type of the creator whose works never die.

Last modified 23 July 2012