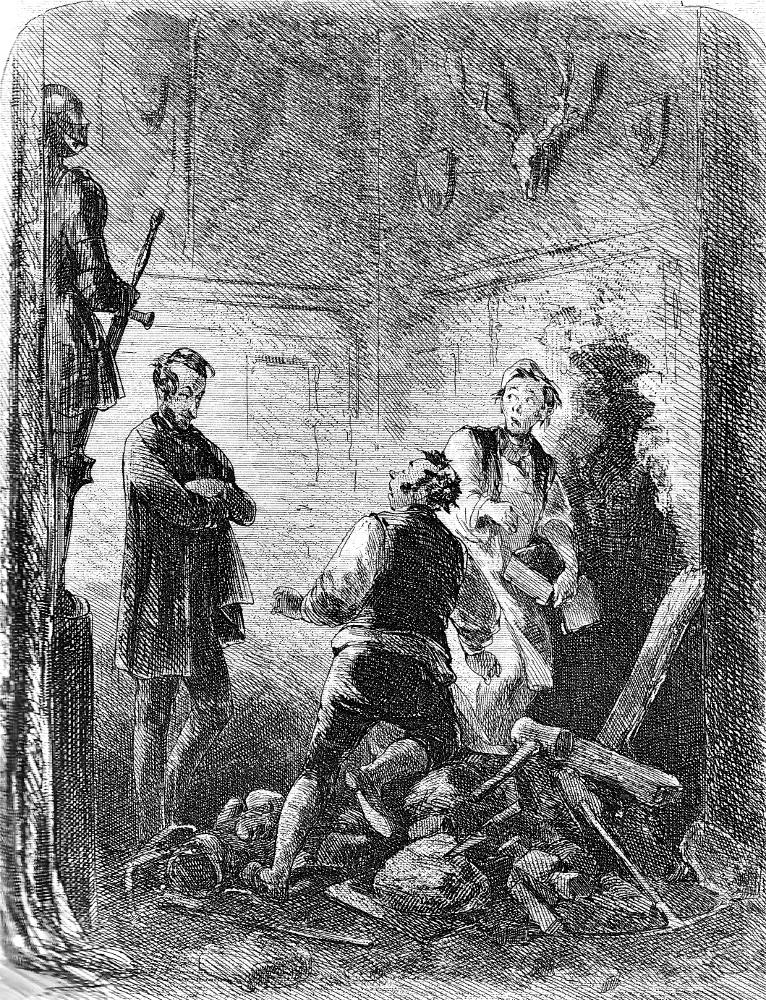

The Discovery

Phiz

Dalziel

December 1848

Steel-engraving, dark plate, facing p. 276.

11.8 cm high by 9.2 cm wide (4 and 7/16 by 3 and 7/16 inches), framed.

Eighteenth illustration for Roland Cashel, published serially by Chapman and Hall (1848-49).

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Providence Confers upon Linton the Corrigan Deeds

Linton now drew nigh, as he overheard these words, and stationing himself at a small window, beheld the two men as they laboured to detach what seemed a heavy stone in the wall.

“It's not a plate of iron, but a box,” cried one.

“Hush,” said the other, cautioning silence; “if it's money there's in it, let us consider a bit where we'll hide it.”

“It sounds empty, anyhow,” said the first, as the metal rang clearly out under the hammer. Meanwhile Linton stood overwhelmed at the strange connection between the dream and the discovery. “It is a box, and here's the key fastened to it by a chain,” cried the former speaker. He had scarcely succeeded in removing the box from the wall, when Linton was standing, unseen and noiseless, behind him.

“We'll share it fair, whatever it is,” said the second.

“Of course,” said the other. “Let us see what there is to share.” And so he threw back the lid, and beheld, to his great dismay, nothing but a roll of parchment fastened by a strap of what had once been red leather, but which crumbled away as he touched it.

“'Tis Latin,” said the first, who seemed the more intelligent of the two, after a vain effort to decypher the heavily engrossed line at the top.

“You are right,” said Linton; and the two men started with terror on seeing him so near. “It is Latin, boys; it was the custom of the monks to bury their prayers in that way once, and to beg whoever might discover the document to say so many masses for the writer's soul; and Protestant though I be, I do not think badly of the practice. Let us find out the name.” And thus saying, he took up the roll and perused it steadily. For a long time the evening darkness — the difficulty of the letters — and the style of the record, impeded him, but as he read on, the colour came and went in his cheek, his hand trembled with agitation, and had there been light enough to have noted him well, even the workmen must have perceived the excitement under which he laboured.

“Yes,” said he, at last, “it is exactly as I said; it was written by a monk. This was an old convent once, and Father Angelo asks our prayers for his eternal repose, which assuredly he shall have, heretic that I am! Here, boys, here's a pound-note for you; Father Rush will tell you how to use it for the best. Get a light and go on with your work, and if you don't like to spend the money in masses, say nothing about the box, and I'll not betray your secret.” [Chapter XXX, "Miss Leicester's Dream and Its Fulfilment," pp. 277-278]

Commentary: Fulfilling the Expectation of "Old walls have mouths as well as ears."

And what is this mysterious manuscript whose location had come to Mary Leicester in a dream? Lever prepares us for this revelation through the chapter's epigraph from "The Convent," supposedly a play. Proof that her grandfather still owns the O'Regan estates, thought forfeited a century earlier, has fallen into Linton's grasp:

The document, surmounted by the royal arms, and engrossed in a stiff old-fashioned hand, was a free pardon accorded by his Majesty George the Second to Miles Hardress Corrigan, and a full and unqualified restoration to his once forfeited estates. Certain legal formalities were also enjoined to be taken, and certain oaths to be made, as the recognition of this act of his sovereign's grace. [279]

Linton thus plans to marry Mary Leicester in order to secure the whole Tubbermore estate for himself. As early as Chapter Thirteen Lever had hinted that the plot surrounding the ownership of Tubber-beg might hinge upon the discovery of century-old documents that would assert old Corrigan's claim to the whole ancient estate:

"I was going to bid you tell him that we have an old claim on the whole estate that some of the lawyers say is good, — that the Crown have taken off the confiscation in the time of my great father, Phil Corrigan; but sure he wouldn't mind that, — besides, that's not the way to ask a favour.” [Chapter XIII, "Tubber-beg," 127]

Phiz has derived the apparent apprehensiveness of the masons from the brooding Tom Linton's suddenly interrupting them after they have smashed a hole in the wall of the chapel, and discovered Father Angelo's steel box, in exactly the location that Mary Leicester has dreamed it would be found.

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. With 39 illustrations and engraved title-vignette by Phiz. London: Chapman & Hall, 1850.

Lever, Charles. Roland Cashel. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Vols. I and II. In two volumes. Boston: Little, Brown, 1907. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: 19 August 2010.

Steig, Michael. Chapter One, "Illustration, Collaboration, and Iconography." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 1-23.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Roland

Cashel

Next

Created 29 December 2022