illiam Wilkie Collins, inventor of the Sensation Novel, was born on 8

January 1824, the son of the popular landscape painter, William Collins, R. A. According to John Bowen, "Collins had an unusual childhood, as singular in its way as that of Dickens or the Brontës. . . . Although Wilkie had an affectionate childhood it was anything but bohemian or liberal, and his father's High Tory Evangelicalism gave him a distatste for respectable piety and organized religion that was to last his life" (4).

At age 22, he became a law

student at London's Lincoln's Inn. Collins was called to the bar in

1851, the same year in which he first met novelist

Charles Dickens, with whom he is still so closely

associated that he has been called "the Dickensian Ampersand." He never practised law, adopting literature as his

profession instead. Between 1848 and his death in 1889,

he wrote 25 novels, more than 50 short stories, at least

15 plays, and more than 100 non-fiction pieces. A close

friend of Dickens from their meeting in March 1851

until Dickens' death in 1870, Collins was one of the best

known, best loved, and, for a time, best paid of Victorian

fiction writers.

illiam Wilkie Collins, inventor of the Sensation Novel, was born on 8

January 1824, the son of the popular landscape painter, William Collins, R. A. According to John Bowen, "Collins had an unusual childhood, as singular in its way as that of Dickens or the Brontës. . . . Although Wilkie had an affectionate childhood it was anything but bohemian or liberal, and his father's High Tory Evangelicalism gave him a distatste for respectable piety and organized religion that was to last his life" (4).

At age 22, he became a law

student at London's Lincoln's Inn. Collins was called to the bar in

1851, the same year in which he first met novelist

Charles Dickens, with whom he is still so closely

associated that he has been called "the Dickensian Ampersand." He never practised law, adopting literature as his

profession instead. Between 1848 and his death in 1889,

he wrote 25 novels, more than 50 short stories, at least

15 plays, and more than 100 non-fiction pieces. A close

friend of Dickens from their meeting in March 1851

until Dickens' death in 1870, Collins was one of the best

known, best loved, and, for a time, best paid of Victorian

fiction writers.

In Dickens's second weekly journal, All the Year Round, in 1862-63 he published No Name serially. His best known works, immensely popular in the mid-nineteenth century, especially in the United States, are The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1867). After his death, his reputation declined, but Collins's work is currently enjoying a critical and popular resurgence. A continuing source of fascination for the reading public is the relationship between Wilkie's private life and his writing. The "original" for the woman in white was Mrs. Caroline Graves, with whom Collins lived for most of his life after 1859, though he had three children by Martha Rudd.

At the age of 28, in March 1851, Collins, then a law student at Lincoln's Inn, met the icon of Victorian popular culture, Charles Dickens, who knew Wilkie's father, the landscape artist and Royal Academician, William Collins. Dickens invited the young man to participate in his amateur theatricals, and in the middle of June, 1855, in the children's schoolroom which doubled as a theatre at Tavistock House, Dickens and company performed Collins's The Lighthouse as an adult-oriented entertainment, and so Collins helped to set Dickens on the trajectory which would lead to the full-scale melodrama The Frozen Deep and a young actress named Ellen Lawless Ternan. By the end of August 1855, Collins finished almost five months' work on the play. In February 1856, Collins visited Dickens in Paris. That summer, Collins was Dickens's premier visitor at the pair collaborated on the writing of a new play for Dickens's amateur theatricals, The Frozen Deep, finished in draft by mid-September. Dickens then proposed a walking tour of Cumberland to furnish material for a travel article for Household Words When both became lost in the dark and the mists as they were descending a mountain, Collins sprained his leg and had to be carried down by Dickens.

Throughout the next few years, Collins and Dickens collaborated on short stories such as The Perils of Certain English Prisoners for Household Words (Christmas 1857). After breaking with the publishers of Household Words , Dickens founded a similar weekly journal accessible to all classes of readers, All the Year Round , in 1859, and he first weekly serial instalment of Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White appeared in the same edition of All the Year Round as the last instalment of A Tale of Two Cities: 26 November, 1859. By the time that Collins had finished writing the sensation novel in July 1860, despite a mixed critical reception, it had considerably boosted the journal's sales. In volume form, the novel from its initial publication as a triple-decker brought out by London's Sampson Low, Son, and Company, in mid-August, 1860, broke all previous sales records for novels.

Throughout the 1860s Collins enjoyed a literary celebrity and an affluence almost equal to Dickens's because the Victorian reading public appreciated his subtlety of characterization, his realistic psychological portraiture, and his ingeniously involved plotting. For the elder novelist, plot arose from the interaction of deeply felt characters; for the younger novelist, an apparently random chance (in fact, Providence) outside individual characters' control seems to animate and direct the plot. Together, Dickens and Wilkie Collins wrote such Christmas stories for the annual seasonal issue of All the Year Round as A Message from the Sea (1860), Tom Tiddler's Ground (1861), Somebody's Luggage (1862), Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (1863), and Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy (1864). In March, 1862, he fulfilled his last contractual obligation to All the Year Round with the serial publication of No Name , which Dickens thought extremely clever. Wilkie's sale of the novel's copyright earned him the enormous sum of £4,600. At this triumphant point in his career, Wilkie was compelled by a painful combination of gout, rheumatism, and laudanum addiction to visit continental spas in order to recover his health. Before the age of 40 (in April, 1861) he had signed a literary contract for £5,000 with Smith, Elder — either for a complete novel or a serial to run in the Cornhill (then edited by W. M. Thackeray), chief rival to All the Year Round .

In April, 1861, despite the fact that the publication of No Name in All the Year Round would run into 1862, Collins signed with Smith and Elder. However, periodically, Dickens lured Collins back, most notably for the serial publication of The Moonstone (1867). In the late 1860s, estranged from Dickens, Collins began to decline in health. Distressed by his corpulence, he often went abroad to take the cure at various continental spas. In print as in life secrets and double identities held a fascination for Collins. In 1868, Caroline married — Wilkie even attended the wedding — probably in response to his taking up with Martha Rudd. However, after her marriage she returned to live with Wilkie, who from then on maintained two separate households. Moreover, owing to Wilkie's odd domestic arrangements and his growing opium addiction, Wilkie Collins and his mentor became estranged in those final years of Dickens's life. After Dickens's death in 1870, Collins remained a prolific writer, despite continued ill health. However, his addiction to laudanum had a negative impact on his productivity for the last two decades of his life. Collins, the inventor of "Make 'em cry, make 'em laugh, make 'em wait" books, died on 23 September 1889.

Bibliography for Works on the Life of Wilkie Collins

Ashley, Robert. Wilkie Collins . London: 1952.

Baker, William, et al. Eds. The Public Face of Wilkie Collins: The Collected Letters. 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2005 [added by GPL].

Bowen, John. "Champagne Moments" [review of Collins's letters above]. Times Literary Supplement. (February 3, 2006): 4-5.

Clarke,William M. The Secret Life of Wilkie Collins . London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1989.

Davis, Noel Pharr. The Life of Wilkie Collins . Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1956.

Gasson, Andrew. Wilkie Collins — An Illustrated Guide . Oxford: Oxford University,1998.

Peters, Catherine. The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva (Martin Secker & Warburg), 1992.

Robinson, Kenneth. Wilkie Collins . London: 1951.

For a more complete list of biographical works, see "Books" (p. 230-231) and "Articles" (p. 232) in the Clarke biography.

Related Web Resources

- The Wilkie Collins Appreciation Page (Australian site)

- The Wilkie Collins E-Text Page

- Andrew Gasson's Homepage (UK site)

- Wilkie Collins (Canadian site)

Last modified 12 November 2012

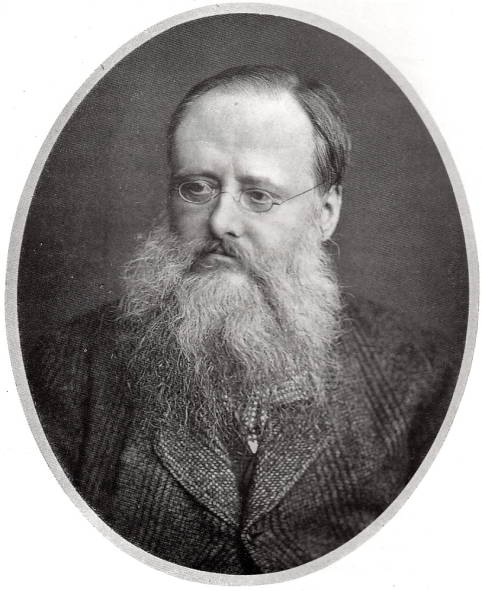

Portrait added 19 July 2021