Directions: (1) Clicking on superscript numbers brings you to notes, which will appear at the bottom of the screen; hitting the back button on your browser (or command + [) returns you to your place in the body of the main text. (2) Click on images to enlarge them.

orn near Edinburgh in 1848, and educated at the city’s Canonmills School (where Robert Louis Stevenson was one of his contemporaries), Stephen Adam showed talent in drawing and painting from an early age.107 This led to his being apprenticed in 1861 to the prominent Edinburgh firm of decorators and stained glass makers, Ballantine & Son. He thus received his earliest training in stained glass from one of the most respected practitioners of the medium in Scotland, James Ballantine (1807-1877). As already noted, Ballantine was critical both of the methods of the Munich glass makers and of the current English practice of imitating medieval glass window designs.

In 1864, the young Adam moved with his family to Glasgow, Scotland’s rapidly expanding city of opportunity, where he became a student at the Glasgow School of Art and Haldane Academy.108 Here, in the following year, he was awarded a silver medal for his work in stained glass. This brought him to the attention of Scotland’s leading stained glass artist of the time, Daniel Cottier, who had also worked for Ballantine in Edinburgh before setting up on his own in the Scottish capital and then moving his firm to Glasgow where, as it was one of the fastest growing and wealthiest cities in Europe, there was no shortage of orders for stained glass -- “Second City of Empire and First City of Glass,” as Michael Donnelly described it in the title of Chapter 2 of his Scotland’s Stained Glass: Making the Colours Sing (Edinburgh: The Stationary Office, 1997). Cottier, who was already beginning to win international recognition (at the 1867 Paris Exhibition, an armorial window by him was to earn high praise for its “superb harmony of colours,” be judged “the finest ornamental window in the Exhibition,” and win a prize109), took Adam into his workshop toward the end of 1865 and by the following year the 18-year-old had probably completed his apprenticeship. As a qualified journeyman, he may thus have had a hand in the execution of some of Cottier’s important commissions in those years, notably for the windows in architect William Leiper’s Dowanhill Church in the West End of Glasgow (built in 1865-66, now restored as “Cottier’s Theatre,” a restaurant, bar, and cultural venue) and for at least two of Alexander (“Greek”) Thomson’s buildings -- the handsome villa known as Holmwood House in Cathcart, a district in Glasgow’s South Side (built in 1859), and the magnificent Queen’s Park United Presbyterian Church in the Queen’s Park district, also in Glasgow’s South Side (1869, destroyed by an incendiary bomb during World War II). 110 Adam acknowledged his indebtedness, particularly in the matter of color to his former employer and master.111

Figure 1. Daniel Cottier. Spring. 1873-75.

Cottier may well also have influenced Adam in the matter of design. While in London Cottier had enrolled in F.D. Maurice’s Working Men’s College (image) where he was in contact with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, the young Edward Burne-Jones and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood. The clear, flowing lines of many of his designs demonstrate an affinity with the work of his contemporaries in the Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements, which he passed on to Adam. (Fig. 1) This Pre-Raphaelite influence on Adam is easily discerned by comparing the Maryhill panels, despite the difference in subject matter, with Rossetti’s Sir Tristram and la Belle Ysoude, made for Harden Grange in Yorkshire in 1862.

After Cottier left Glasgow for London in 1869 and went on to set up studios and art dealerships in New York and Sydney, Australia, the by then 22-year-old Adam, in partnership with David Small, another native of Edinburgh and former fellow-apprentice at the Ballantine studio, opened a stained-glass workshop of his own at 121 Bath Street in the fast developing western part of Glasgow’s city center.112 Though Small appears to have “remained quietly in the background,”113 and the partnership was dissolved in 1885, one of the panels in Maryhill Burgh Halls, “The Boatbuilder,” does bear the company name “Adam & Small,” as do several church windows. Adam did collaborate informally but quite regularly with another of Cottier’s assistants, the gifted Andrew Wells who, however, left for Australia in 1886, where he joined the firm Cottier had set up in Sydney, returning to Glasgow in the following decade as a partner in the firm of J. & W. Guthrie and Andrew Wells. 114 Over the years, as his workshop received more and more commissions, Adam also employed several younger men who went on to win recognition as stained glass artists in their own right, notably his own son and, for a time, partner, Thomas Annan Jr. (who, however, in an unexplained dispute with his father left the firm in 1904, opened a studio of his own in Glasgow, and then, in 1916, emigrated with his family to America), David Gauld, William Tait Meikle, and Alf Webster. (Figs. 2-5) By the time of Adam’s death in 1910, Webster had virtually taken over the studio.

Left: Figure 2. Stephen Adam Jr. Suffer the Little Children. St. James the Less Episcopal Church, Bishopbriggs, Glasgow. Middle left: Figure 3. Stephen Adam Jr. Doorway. 8 Belhaven Terrace, West End, Glasgow. Middle right: Figure 4. Stephen Adam and Alf Webster. Ecce Ancilla Domini. St. Nicholas Church, Lanark. Right: Figure 5. Alf Webster. Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes. Templeton Memorial Window, centre light, lower panel. Lansdowne Church, Glasgow. 1911.

Most of the firm’s commissions, as Ian Mitchell has pointed out (see Appendix I), were inevitably for churches. The fashion for memorial windows, which set in around mid-century, gave no sign of slowing down and constituted an extremely important source of income for every stained glass workshop. 115 Adam himself, in an appendix to the second edition (1904) of his pamphlet Truth in Decorative Art (1896), lists, as “a few” that “may be mentioned,” just under 100 “among the most important church memorial windows designed and executed in recent years by Stephen Adam.”

Nevertheless, the firm’s business ranged widely and many windows were designed for public buildings, such as the town halls of Annan and Inverness, the Sick Children’s Hospital in Glasgow, the Carnegie Library in Ayr (opened in August 1893 in the presence of the benefactor, Andrew Carnegie, himself — see Fig. 10), as well as for the villas and terrace houses of prosperous Glasgow merchants in the city’s West End and South Side (figs. 6, 7, 8), the castles and mansions of the well-to-do in Scotland and Ireland, commercial premises, such as Pettigrew and Stephens department store on Sauchiehall Street in Glasgow, and – in Adam’s own description -- “High Class Restaurants,” such as “Spiers & Pond’s, Blackfriars, London” and “the Grosvenor, Gordon Street” in Glasgow, and “leading steamships and yachts.”

Three windows by Stephen Adam for private homes in Glasgow and one for a library. Left: Figure 6. Cleopatra. “The Knowe.” Pollokshields. 1890. Middle left and right: Figures 7 & 8. Windows at 2 Devonshire Gardens. Right: Figure 9. Stephen Adam, window at Carnegie Library, Ayr.

Bars and public houses, such as the Imperial Bar, still doing business in Howard Street in central Glasgow, also figured among the firm’s clients. (Fig. 11) By the beginning of the twentieth century the Adam studio was one of the leading stained glass studios in Scotland with, in addition, a considerable overseas clientele.116

Left: Figure 11. Stephen Adam, stained glass panels above the bar at Imperial Bar, Howard Street, Glasgow. Right: Figure 12. St. Andrew's in the Square, Glasgow. General view looking toward the Adam window.

Glasgow and its Environs: A Literary, Commercial, and Social Review, Past and Present; with a Description of its Leading Mercantile Houses and Commercial Enterprises, published by Stratten & Stratten in London in 1891, devoted a long entry to “Stephen Adam & Co. Glass Stainers and Decorators, 231 St. Vincent Street, Glasgow,” asserting that

under Mr. Adam's management the house has become one of the most noted concerns in Scotland in its line, and has maintained a splendid reputation in every branch of decoration by means of stained glass. [. . .] The house has carried out many notable contracts both in connection with ecclesiastical window work, public institutions, hotels, restaurants, banks, etc., etc. [. . .] The trade of the house extends over the whole of the United Kingdom and the Colonies. The business is constantly experiencing extension in scope and, through Mr. Adam’s influence, becomes more widely known every day. As an evidence of the high popularity attained by the house, we may mention that within the past ten years, Mr. Adam has completed for patrons no fewer than two hundred and twenty stained glass memorial windows in various parts of the world.

The company’s premises, as described by the author of the entry, were extensive, comprising “six spacious flats, admirably equipped in all parts, and devoted to (1) Workshops for lead working; (2) The drawing and designing of cartoons and painting of patterns for approval, before proceeding to the final operations; (3) Glass painting and staining workshops; (4) The kilns for firing the glass after the process of staining; (5) For stock of material; and (6) Packing department.” The operations associated with each of these departments, the reader is informed, “afford employment to executants of the highest skill and talent.” The entry closes on a brief biographical sketch of Stephen Adam himself, “a gentleman of exceptional culture and erudition” and a leading citizen of his adopted city, being “a prominent member of the Philosophical Society and of the Society of Literature and Arts,” and well known and admired for his lectures and writings on the decorative arts. “In every sphere in which this gentleman exercises his influence,” we are informed, “he is a decided acquisition, and his counsels are received with the most marked respect and attention.” That was in 1891, but in 1877 when he was commissioned to produce the panels for the Maryhill Burgh Halls, Adam was not yet 30 years old and had been in business for only a few years. Moreover, except for some very general stylistic features nothing in his previous practice appears to anticipate the Maryhill panels -- and, strikingly, very little in his subsequent practice recalls them.

Left: Figures 13 & 14. Stephen Adam, three-light window and detail, St Andrew's in the Square, Glasgow. Right: Figure 15. Detail from window in the former Belhaven United Presbyterian Church (now Greek Orthodox Cathedral), Glasgow. 1877.

One of his earliest works, produced in 1874 when he was just 26 years old, was a beautiful three-light memorial window designed for the handsomely refurbished eighteenth-century St. Andrew’s Church in Glasgow’s St. Andrew’s Square – one of the finest church buildings of its time in Scotland. (Figs. 12-14) Three years later, around the same time that he began working on designs for the Maryhill Burgh Halls panels, he created the stained glass windows for Glasgow architect James Sellars’ Belhaven United Presbyterian Church in the city’s prosperous West End. (Fig. 15) In Iain Galbraith’s words, a special feature of these windows was the “use of fruit and foliage motifs. These are beautifully drawn and show the influence of Japanese art, delicate and incisive in muted shades of blue, silver, green and gold, and of William Morris in the willow-patterned background. These decorative panels function as foils for the subtly-coloured figure panels, based upon illustrations from the parables and which constitute independent colour studies on their own.” 117 In 1877 Adam also produced the elaborate three-light Baird memorial window in the parish church of the village of Alloway in Ayrshire, the birthplace of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. (Figs. 16) -19

Figures 16-19. Stephen Adam. Baird South Window. Alloway Parish Church. Right three: Details: Middle left: The Nativity. Middle right: Adoration of the Magi. Right: Angel.

The clean, modern design of these early works, the effective use of the leadlines to enhance and highlight the composition, and the rich colors of the glass itself, along with moderate use of paint to give expressiveness to the faces and avoidance of the traditional canopies above the figures, show the influence of Cottier, William Morris, and Burne-Jones, and, in general, demonstrate the strength and clarity that were to be hallmarks of Adam’s designs throughout his career. The “mosaic” effect of the relatively small glass pieces making up the overall design -- which becomes even more pronounced later, as in the windows for the Clark Memorial Church in Largs of 1892 (Figs. 20-23), and contrasts markedly in both conception and impact on the viewer with the Maryhill panels -- confirms visually Adam’s commitment in his writings to the “Mosaic” rather than the “Enamel” or “Mosaic-Enamel” method. Except for the traditional subject matter, however, there is nothing antiquarian about Adam’s lively and expressive style.

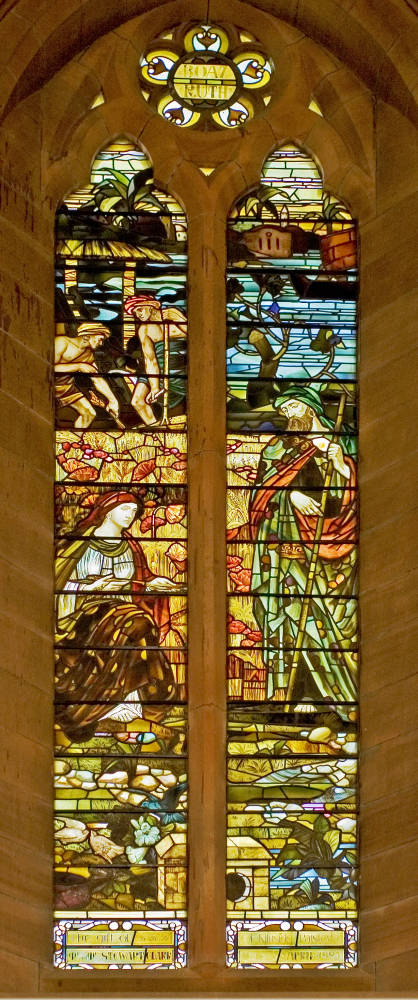

Left: Figure 20. Stephen Adam. West or Preacher’s Window Clark Memorial Church, Largs, Ayrshire. 1892. Figures 21-23. Three windows by Stephen Adam for the Clark Memorial Church in Largs of 1892. Left: David Playing before Saul. . Middle: Ruth and Boaz. Right: Jesus Visits Martha and Mary.

As already noted, he himself declared that he had been “greatly influenced by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, William Morris and Puvis de Chavannes” and that “as a colourist, I found my master in the late Daniel Cottier.” 118 On several occasions he also referred admiringly to the clean lines of the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century neo-classical artist John Flaxman and, as we have seen, he appreciated the drawing skills of the Bavarians, most of whom belonged to or were influenced by the school of so-called “Nazarene” artists of the early decades of the nineteenth century -- a group that, in revolt against the alleged decadence of art in the age of the baroque and the rococo, advocated avoidance of excessive chiaroscuro and “bold brushstrokes” and a return to the practice of fresco and to the clearer, simpler lines of the early Renaissance.

Four paintings by the Nazarenes. Left: Figure 24. Friedrich Overbeck. Der Ostermorgen [Easter Morning]. Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf. c. 1819. Middle left: Figure 25. Franz Pforr. Sulamith und Maria. 1810-1811. Middle right: Figure 26. Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld. Saint Roch giving alms. 1817. Right: Figure 27. Joseph von Führich. Jacob Encountering Rachel. 1836.

Though now neglected, except in their native Germany, the Nazarenes exercised enormous influence in Britain as well as Germany and France in the early to middle decades of the nineteenth century, notably on the widely respected Scottish painter William Dyce (1806-1864; see Fig. 28, Dyce's Jacob and Rachel), who had frequented the Nazarene artist Friedrich Overbeck’s studio in Rome and with whose work both as a painter and an occasional stained-glass designer Adam had to be familiar, and on many Pre-Raphaelite painters or painters closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. (Figs. 24-27)

In one case, documented by William Vaughan in his German Romanticism and English Art, a painting by Overbeck representing the death of Joseph was directly copied by an English stained glass artist for the little church at Church Lench in Worcestershire.119 (Figs. 29, 30)

Figure 29. Left: Johann Friedrich Overbeck. Death of Joseph. 1857. Right: Figure 30. Frederick Preedy. Death of Joseph. All Saints Church, Lench. 1858.

) Leading members of the first and second Pre-Raphaelite generations, such as Burne-Jones and Rossetti, both of whom Adam cites as significant influences on him, had met with Overbeck in Rome and responded positively to the attempts of the founder of the Brotherhood of St. Luke (Lukasbund), as the original group of rebellious young students at the Vienna Academy had styled themselves, to reform the principles and practice of art. 120

Adam’s criticisms of the strongly Nazarene-influenced Munich school, as noted earlier, were nuanced. Even while rejecting the objectives of High Renaissance and post-Renaissance painters for his own medium of stained glass, as the Nazarenes had already done for painting, he sought, like the Munich school, to design figures in a more “natural” modern style, rather than according to the conventions of medieval stained glass, and he aimed to give his figures the grace and expressiveness expected by viewers familiar with the paintings of Burne-Jones, Rossetti or Millais. 121 These features continued to characterize his work throughout his career.

Nevertheless, the style and indeed the whole conception of the Maryhill panels seem quite distinctive in Adam’s work as a whole. The colors are unlike the more vivid and varied colors which he used in most of his work and for which, like his “master” Cottier, he was much admired. The disposition of the figures is spatially balanced and while their activity is vividly conveyed, there is no striving for dramatic, let alone theatrical effect. The overall design is exceptionally clear, spare, and simple and there is a total absence of the decorative motifs (leaves, flowers, etc.) and “diapering” that accompanied most of the ecclesiastical stained glass windows at the time, including Adam’s, and that were an essential element also of much decorative domestic stained glass. As noted, the Maryhill panels are distinctive even in relation to Adam’s designs for the Aberdeen Trades Hall, which are far more conventional.

Strikingly, many of the panels representing industry and commerce that the Adam studio executed years later for the boardroom of the new Clyde Navigation Trust building by the noted Glasgow architect J.J. Burnet (1883-86, extended 1906-08), while in some respects more realistic, more dramatic, and less idealized than the Maryhill panels -- in the shipbuilding “Riveters” panel, for instance, as Ian Mitchell pointed out to the present writer, the actual movements of the workers had clearly been studied with care -- are also more conventional in design and color, as well as in the costumes and disposition of the figures. (Figs. 31-34)

Figures 31-34. Four of Stephen Adam’s windows in Clydeport (1908) depicting business and occupations. Left two: Commerce. Right two: Engineering.

Since the distinctiveness and originality of the Maryhill panels are best appreciated against the background of Adam’s work over the course of his career, as “the true successor of Daniel Cottier and Scotland’s foremost artist in stained glass,”122 it is desirable that the reader be apprised of the general outlines and characteristics of that work. Fortunately, it has been the object of careful analysis by three scholars, Michael Donnelly, Gordon Urquhart, and Iain Galbraith, and Dr. Galbraith has generously agreed to contribute his insights to the present volume. (See Appendix II)

A large window overlooking the Oyster Bar of Edinburgh’s Café Royal for which the Ballantine company designed several impressive figures of modern sportsmen in the 1890s and which shows the influence of the burgeoning Aesthetic movement also remains closer to current stained glass practices than Adam’s Maryhill panels of the late 1870s. (Fig. 38)

Figure 35. James Ballantine company. Rugby and Cricket. Bar, Café Royal, Edinburgh.

In addition, a chronological list of Adam’s work has been compiled (Appendix III), in order to convey some sense of its range and character. Unfortunately, the list remains provisional and incomplete. Adam’s work for private homes, businesses, and secular institutions proved difficult to trace and date; and due to the loss of documentation, some attributions of ecclesiastical windows to the Stephen Adam studio remain speculative and uncertain. Moreover, a studio attribution in itself, as pointed out in Part I, does not identify which member of the studio was primarily responsible for the design. In the years of his studio’s greatest activity and success, Adam employed a number of gifted assistants, as we saw, any of whom might have had a hand in or even primary responsibility for a work bearing the studio’s name.123 On his side, Adam occasionally undertook commissions on behalf of other glass artists, so that work usually attributed, for instance, to William Meikle & Son, could well have been carried out by Adam.124

In an appendix to a 1904 reprint of his pamphlet of 1896 on “Truth in Decorative Art,” Adam provided a select list -- largely no doubt as a form of advertisement -- of “the most important Church Memorial Windows designed and executed in recent years by Stephen Adam,” followed by a list of “Mansions and Public Buildings” for which he made decorative windows. As none of the 130 windows listed is dated and as it is difficult to determine exact dates for many of them or even their current condition, only a few have been included in our chronological list. Adam’s own two lists have therefore been reproduced in Appendix III as published by him.

Notes

In this web version some of the original endnotes have been converted to in-text page citations, so the notes below do not form a complete sequence.

107 For the brief account of Adam’s early life and career given here. I am indebted to Iain Galbraith, “Always happy in his designs: the legacy of Stephen Adam,” The Journal of Stained Glass (2006), 30:101-15, to Michael Donnelly, Glasgow Stained Glass: A Preliminary Study (Glasgow: Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, 1981), on p. 13, and to Donnelly’s later work, Scotland’s Stained Glass. Making the Colours Sing (Edinburgh: The Stationary Office, 1997), p. 32.

108 The Glasgow Government School of Design, founded in 1845, changed its name in 1853 to the Glasgow School of Art. On receipt of funding from the Haldane Academy Trust, set up in 1833 by a local engraver, it was required to rename itself the Glasgow School of Art and Haldane Academy. The “Haldane Academy” part of the title was dropped in 1892.

109 On Cottier’s exhibit at the 1867 Paris International Exhibition, see Barbara Millar, “Andra! Slabber oan some broon there, just beside the wibble-wabble,” Scottish Review, no. 391 (19 April 2011) (online version), According to the writer of the report on stained glass in Reports of Artisans Selected by a Committee Appointed by the Council of the Royal Society of Arts to Visit the Paris Universal Exhibition 1867 (London: Bell and Daldy, 1867), pp. 81-82, “Cottier (Glasgow) has a magnificent ornamental window, in the renaissance style: in the centre, arms on a fanciful shield; splendid design; ornament free and graceful; well proportioned columns, with a richly decorated pediment at the top, surrounded with cupids; superb harmony of colours. This window, in my estimation, is the finest ornamental window in the Exhibition. I heard its merit was recognized by the jury.”

110 Fifteen years after Thomson’s death in 1875 Adam created a decorative panel, Cleopatra, for The Knowe – another South Side villa designed by the architect, whose distinctive style was almost as “Egyptian” as it was “Greek.”

111 “If I may speak confidently of my work as a colourist, I found my master in the late Daniel Cottier, the eminent glass painter.” (From Truth in Decorative Art [Glasgow: Carter & Pratt, 1895], p. 33, cit. in Iain B. Galbraith, “Always happy in his designs: the legacy of Stephen Adam,” p. 101)

112 There is some uncertainty as to the identity of Small. One view is that Adam’s partner was David Small (1846-1927), a painter and water-color artist whose scenes of Scotland -- in particular, of Old Glasgow and, later, of Dundee -- continue to figure in the catalogues of modern auction houses. In another view, Adam’s partner was a glass-stainer by the name of David Small, who seemingly had a studio in Edinburgh and was reported in The British Architect (January 15, 1874, p. 47) to have proposed a new method of painting on plate glass. This would seem to be more likely in light of a reference to him in a posting about Stephen Adam on a Glasgow University website: “Former house-painter Small (1831–1886) retained his own Edinburgh glass 'embossers and fancy decorators', which he ran on his own from 1877. (Edinburgh Gazette, 22 September 1868, p. 1175; 22 October 1878, p. 807.)” [website]. It has also been suggested, however, on the basis of a Dundee newspaper obituary of the water-color artist David Small, that Adam’s partner was in fact Small’s brother William and that the latter may have been in charge of the financial side of the Adam studio and for that reason “remained quietly in the background.” (E-mail from William Black of 11 December 2015) The Adam company premises moved several times within the heart of the new center of Glasgow (259 West George Street, 231 St. Vincent Street, 199 and 168 Bath Street).

113 Michael Donnelly, Glasgow Stained Glass: A Preliminary Study (Glasgow: Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, 1981), p. 13.

114 Morag Cross, “Andrew Wells, Stained Glass artist,” Magazine of The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland (Spring 2014): 24-25.

116 In Sydney, Australia, for instance, where there are Adam windows from 1907 in the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; see RPA Heritage News, 2.4 (January, 2012). For a list of windows and panels “completed in recent years” and installed in “Mansions and Public Buildings,” see the appendix to the second edition of Truth in Decorative Art (Glasgow: printed by Carter and Pratt, 1904), reproduced here in Appendix III.

Among the mansions: Blyth Hall, Newport, Dundee [1877, extended 1890]; Drumalis Castle and Cairn Castle, near Larne, County Antrim, Ireland; Dundas Castle, South Queensferry, near Edinburgh; Gallowhill House, Paisley [built by the architect James Salmon in 1869]; Ralston House, Gartmore House, Kilnside House, and Ferguslie House all also in Paisley; Moreland House, Skelmorlie, Ayrshire [1862, extended by John Honeyman 1874 and by Honeyman and Keppie, 1893-94]; The Cliff in nearby Wemyss Bay, Renfrewshire; Cornhill Mansion, Biggar, Lanarkshire; Mauldslie Castle, Carluke, Lanarkshire [an Adam building with extensions in 1860 and 1891]; Auchendrane House near Ayr and Beleisle House near Prestwick, Ayrshire, and various mansions in Perthshire belonging to the Pullar family of the celebrated dyeworks (“Dyers to the Queen” in 1852) and then of the nationally known dry cleaners, Pullars of Perth. In addition to the Pullars, the Coats and Clark families of the flourishing, internationally active Paisley thread industry were frequent clients of Adam, whence the large number of commissions for houses in Paisley and for Dundas Castle, purchased by one of the Clarks in 1899. Many of the houses in Adam’s list are now upmarket hotels. (My thanks to Gordon R. Urquhart for bringing this list to my attention and providing me with a photocopy of it.)

117 Iain B. Galbraith, “Always happy in his designs: the legacy of Stephen Adam,” The Journal of Stained Glass (2006), 30: 101-15, on p. 104.

118 Stephen Adam, Truth in Decorative Art, cited in Galbraith, p. 101.

119 On the Nazarenes in England, see William Vaughan, German Romanticism and English Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press/The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1979), passim; also my articles "Unwilling Moderns: the Nazarene painters of the nineteenth century," www.19thc-artworldwide.org, Fall issue, 2003, 72 pp., and “Beyond Modern: The Art of the Nazarenes,” Common Knowledge, 14 (2008): 45-104. The direct inspiration of Overbeck’s painting for a memorial window at Church Lench by James Preedy and and the incorporation of designs by Overbeck into murals by the Gothic Revival architect George Edmund Street in the chancel of the restored thirteenth-century Church of St. Peter and St. Paul at Sheviock in Cornwall are documented in Vaughan, pp. 228, 244-45.

120 See William Holman Hunt’s personal testimony in his Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2nd ed. 2 vols. (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1914), 1: 74 and 85.

121 Referring to unpublished Occasional Papers by Sally Rush, now in the Art History department of Glasgow University, and Linda Cannon, a fellow graduate of the Glasgow School of Art, Galbraith writes of the Glasgow School, for which Cottier and Adam prepared the way, that it was resolutely modern in its focus on art. It “rejected the revivalist approach which was controlled by religion and architecture and was basically artistic in its approach, not dictated to by religion and interested in glass per se.” (“Stained Glass in Scotland: A Perspective,” The Church Service Society Record, 47 [2012]: 14-24, on p. 20)

122 Michael Donnelly, Scotland’s Stained Glass. Making the Colours Sing (Edinburgh: The Stationary Office, 1997), pp. 36-37.

123 See note 20 above. There can be uncertainty about who was responsible even in the case of the Maryhill panels, which were produced at a fairly early point in the Adam studio’s history. Thus in the panel depicting the Railway Porter, on a parcel with the label “Newcastle-Maryhill,” Michael Donnelly points to the signature, etched with a diamond, of Joseph Miller, a skilled glass-painter and cartoonist, who was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne into a family of glassmakers and who was thus about the same age as Adam himself when he joined the latter’s studio. (Scotland’s Stained Glass. Making the Colours Sing, pp. 35-36) Miller was probably active in executing Adam’s design.

124 See Gordon R. Urquhart, A Notable Ornament: Lansdowne Church, p. 146.

Created 8 June 2016