In transcribing the following article from the Hathi Trust online version of a copy of the Illustrated London News in the University of Chicago Library, I have used ABBYY software to produce the text below and added links to material in the Victorian Web. This article is of particular interest because it shows that by the 1840s the government had already created large number of well-funded schools of design for both men and women long before the Great Exhibition of 1851, which is usually credited with the recognition that England needed to train designers in order for its products to compete internationally. — George P. Landow

.

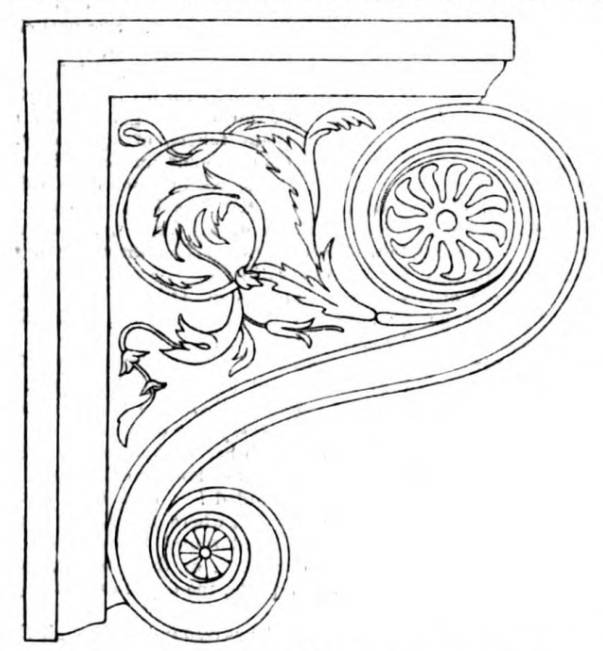

School of Design. Click on image to enlarge it.

The textile fabrics of our manufacturing industry are superior, in the strength and beauty of their structure, to those of all nations, whether of ancient or modern date; but in their forms and decorations they are deficient in taste, and are this moment surpassed by many of the smaller states of Europe. Saxony is superior to us in harmony of colour, Germany in ornamental combinations, and France in the variety, grace, and fitness of its embellishments. This national inferiority has arisen from our neglect of nature in the education of our ornamental designers, and from a mercenary habit of leaving the invention of our putterns to the accidental, unpaid, and uncultivated imaginations of the poor foremen of factories. The lace-runner and tambour-worker of Nottingham, the cotton printer of Manchester, the woollen dyer of Leeds, and the silk weaver of Spitalfields, have each been left to pursue their own fancies, and it been followed that, as their fathers did, so have they done—the old designs have been repeated—or, if they have ventured on any view combination, it has only been a recomposition of old patterns, or a second-hand imitation of “new fashions” imported from the Continent. No artists — no original minds — have ever been brought to rescue the manufacturing arts from their oblivious monotony, unless, indeed, it were the pedantic Kent, who decorated the petticoat of a duchess with the five orders of architecture, or good old Strutt, who added many various powderings of “pepper and salt” to the Derby ribbed hose.

This long indifference to the beauty of our fabrics at length produced its inevitable consequence—a preference for foreign manufactures, and a corresponding decline in our own trade. The Government, alarmed at this state of affairs, consented, at the instance of Mr. Ewart and some other patriotic members of the House of Commons, to take the subject under their consideration, and a special committee was appointed to collect evidence, and frame a report to the House on the general bearings of the case, and on the best means to be used for promulgating in the manufacturing districts and the kingdom at large a knowledge of the art of design. This committee commenced its labours seven years ago, and sat through two sessions of Parliament, during which time they examined a vast number of witnesses from Paris, Lyons, Berlin, &c., and our great manufacturing towns, besides several of our more eminent painters and masters of public seminaries. The evidence thus collected was ably digested, and published in two goodly volumes, which bore united testimony to the facts we have stated, and to the necessity which consequently rested on the Government to take some immediate steps for the education of the people in the principles and practice of ornamental design. A grant of money was immediately made for the establishment of a School of Design in London; and, as the Royal Academy was then about to vacate its apartments in Somerset-house for for the new rooms built for them in the National Gallery, Charing-cross, it was determined those rooms should he devoted to the use of the infant institution. Here, then, in the midst of a locality sacred to the lovers and familiar to the professors of British arts the first council assembled, and the first scholars entered on their labours, and here they have ever since continued. At the commencement of the school the council were fortunate in securing the services of Mr. Dyce, a gentleman combining high classical attainments with a refined taste and great dexterity in all the practical details of ornamental art. This gentleman, before he commenced the organization of the drawing classes, made a tour of the Continent, for the purpose of forming a collection of printed cottons, figured silks, paper-hangings, book-bindings, and stained glass, for the use of the school—a labour of great responsibility, but one which he succeeded in discharging to the lasting benefit of the establishment.

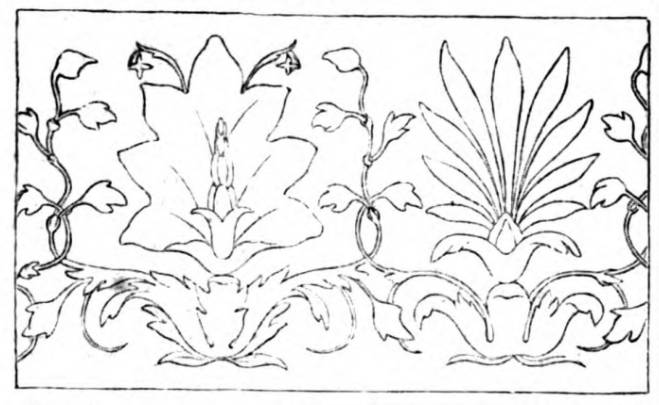

The school at present contains about five hundred students, besides a well-attended class for females. The object steadily pursued in their education is, not so much the acquisition of knowledge and practical skill by a mere study of the ornamental works of the ancients and the school of Raffaelle, as it is the formation of a conceiving principle in the mind of the artist himself. For this purpose they are familiarized, by various exercises, with the forms and colours of the vegetable world, and taught to select and combine them for themselves. They are, however, at the same time zealously instructed in those refined and graceful modes of composition, those hues of beauty, on which the great masters weaved, as it were, their elegant and hitherto illimitable fancies. Beginning with the more simple, they are led on, by successive lessons, to the more complicated, till, by the attainment of the alphabet of the art, and those perceptive powers on which it depends for originality, they become fit for the management of a factory, and the production of those beautiful patterns by which, as in the recent instance of Mr. Cobden’s celebrated purple-and-yellow stripe, ten thousand pounds may be made in one season. We have subjoined, for the information of our country readers, a few examples of the style of the earlier lessons given in the school.

Three examples that appear without captions in the Illustrated London News article.

The following interesting resumé of the last report of the School of Design is from the “Art-Union”:—

The council of the School of Design have laid their report before Parliament, whence is afforded a highly satisfactory review of the progress of the parent and branch institutions. It is by no means yet to be expected that this document could dwell upon any improvement in the taste of our manufactures, but it is sufficiently shown that the best means is adopted in order to secure the best results. Our manufacturers have sustained themselves in the market by the science and energy exerted in their productions; but when legitimate art shall have raised the character of our designs, the question of superiority becomes then but a simple arithmetical thesis; for every thing has already been done for foreign manufactures — but every thing is yet to be done for our own.

It appears from the report that the number of pupils attending the morning school was 47 in October, 1842, and at the end of six months, March 1843, the number was 76. At the former date the number attending the evening school was 170, and at the latter 220 exhibiting, during the six months, an increase of 29 in the morning school, and of 50 in the evening: thus it is sufficiently evident this the institution is appreciated — that the want of such a school has been felt. The programme of instruction comprehends drawing in outline, shadowing, drawing from the round and from nature modelling from the antique and from nature; instruction in colouring, including oil and fresco; instruction in the history and principles of ornamental art, in the antique, medieval, and modern styles; and instruction in design for manufactures, as silk and carpet weaving, calico-printing, and paper-staining. In aid of these branches of study, such books as bear upon the respective subject are circulated among the pupils, who have also the benefit of a series of lectures on calico and silk printing, weaving by hand and by power, figure-weaving, lace-making, type and stereotype founding printing, framing of machinery, engraving and sculpture by machinery, and pottery and porcelain; and moreover, for the promotion of emulation among the students, prizes are proposed for given subjects.

In 1841 the council contemplated the institution of a school for the instruction of females in the art of ornamental design, for many branches of which the tastes and habits of well-informed women so eminently qualify them. This project of the council was carried into effect last October, when the female school was placed under the superintendence of Mrs. M'Ian, a lady well fitted, as her work testify, to realize the best hopes in this department.

In Spitalfields, also, a School of Design has been formed, and it carried on under the direction of a local committee, consisting partly of masters and partly of operatives. This establishment has from time to time been visited by members of the council. The director of the school at Somerset-house has made a report of the state of this school, wherein he says “The drawings which are herewith submitted to the council seem to me to be executed in a bold an artist-like manner, and not only to augur well of the future utility of the school, but to reflect credit on the exertions of the master. Mr. Hudson, and his assistants of the normal class.” When this school was visited at the end of the last year, the number of pupils was 116, but they have since increased to nearly thrice that number they were principally the children of weavers, carpenters, stone masons, cabinet-carvers, &c. &c.”

The council has assisted and established schools at Manchester, York, Coventry, Sheffield, Nottingham, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Norwich, and Birmingham, and have received applications for th establishment and promotion of others at Dublin, Cork, Belfast, Liverpool, Paisley, and Glasgow. The council have not, however extended the same assistance to the latter places, for sufficient reasons which they state, and as waiting reports of the progress of those already established.

In the autumn of 1841 and the beginning of 1842 arrangement were effected for procuring from Paris the collections of casts of ornaments at the École des Beaux Arts: from these a selection has been made and placed in the principal room of the school.

Copies of the “Arabesques” of Raffaelle, in the Loggie of the Vatican, have also been purchased at a cost, including carriage, of £510. The expense of procuring the casts from Paris, that is, the purchase and charges of transport, was £321 1s. 3d.

Considering the increase of the duty attendant upon the growth of this establishment, the council recommend the increase of the salaries of the directors and the master of the evening-school. To that of the director, being £500 per annum, it is proposed to add £100 and that of the latter gentleman, Mr. Herbert, it is also proposed to augment.

This report, on the whole, is of the most favourable kind; indeed more has been effected than the most sanguine expectation could have looked for; and one of the best guarantees for the success of these institutions is the numbers who seek the benefits of the instruction they afford. We have already lamented the inferiority of our designs as compared with those of France; but there are now the best grounds to hope that, in this particular, our productions wil shortly compete in this respect with those of the Continent.

Various other essential improvements are either in progress or in contemplation; among them is the appointment of a competent teacher of wood-engraving, more especially in reference to the female school. And from this female school we anticipate very valuable results; we have reason to know that Mrs. M‘Ian is unremitting in her efforts to render it practically beneficial, and that already it has been productive of great good.

Related Material

- Victorian Decorative Arts and Design (homepage)

- Illustrated London News (homepage)

- The Great Exhibition of 1851 (homepage)

Bibliography

“The Government School of Design.” Illustrated London News. 2 (1843): 375-76. Hathi Trust online version of a copy in the University of Chicago Library. Web. 14 June 2021.

Last modified 14 June 2021