Had it not been disturbed by an unexpected lockdown, 2020 would have been marked by many more cultural events. In England, all animal lovers would have commemorated the tercentenary of the birth of Gilbert White (1720-1793), the author of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, his only book, published in 1789. Pallant House Gallery, in Chichester, is one of the institutions where twentieth-century British art is most regularly honoured, and its director, Simon Martin, duly honoured the memory of his almost neighbour – Selborne, in Hampshire, is only 30 miles away from Chichester – with an exhibition held from 5 August to 4 November (it was originally planned to run from March to June), entitled "Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists." The ambition of the show was to celebrate "the rich artistic legacy of Gilbert White's seminal book", as claimed in a promotion video.

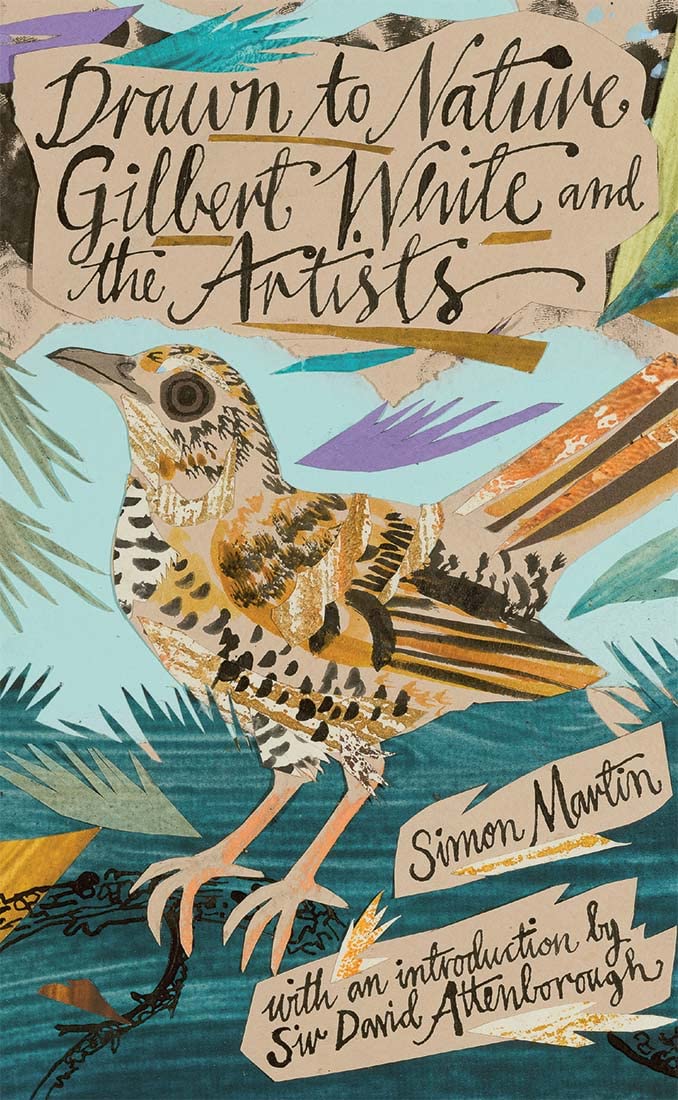

The volume published by Pallant House Gallery does not claim to be a catalogue accompanying the exhibition: while it does include most of the information one might expect from such a publication, it also constitutes an homage to White and his modern illustrators, in a somewhat more academic format than ordinary exhibition catalogues. In particular, it contains several other texts, alongside Simon Martin's foreword and two essays: three poems written by White himself between 1745 and 1769; a famous essay published by Virginia Woolf, published in 1939 in the New Statesman and Nation; "Posthumous Letter to Gilbert White," a blank verse poem written by W.H. Auden in the very year of his death, 1973; as an introduction, a biographical sketch by Sir David Attenborough, first published in The Gilbert White Museum Edition of The Natural History of Selborne by Gilbert White in 1977 (for non-British readers, Sir David Attenborough, born in 1926, is an extremely popular writer, broadcaster and natural historian); and two recent poems inspired by White, one by Jo Bell (2015), another commissioned to Kathryn Bevis by Winchester Poetry Festival and Hampshire Cultural Trust as part of the celebration of the 300th anniversary of White's birth. Obviously, the book is also lavishly illustrated, mainly in black and white (most of the works are thenselves prints of book illustrations) but quite a few of them are fully coloured, like the gorgeous jacket designed by Mark Heald.

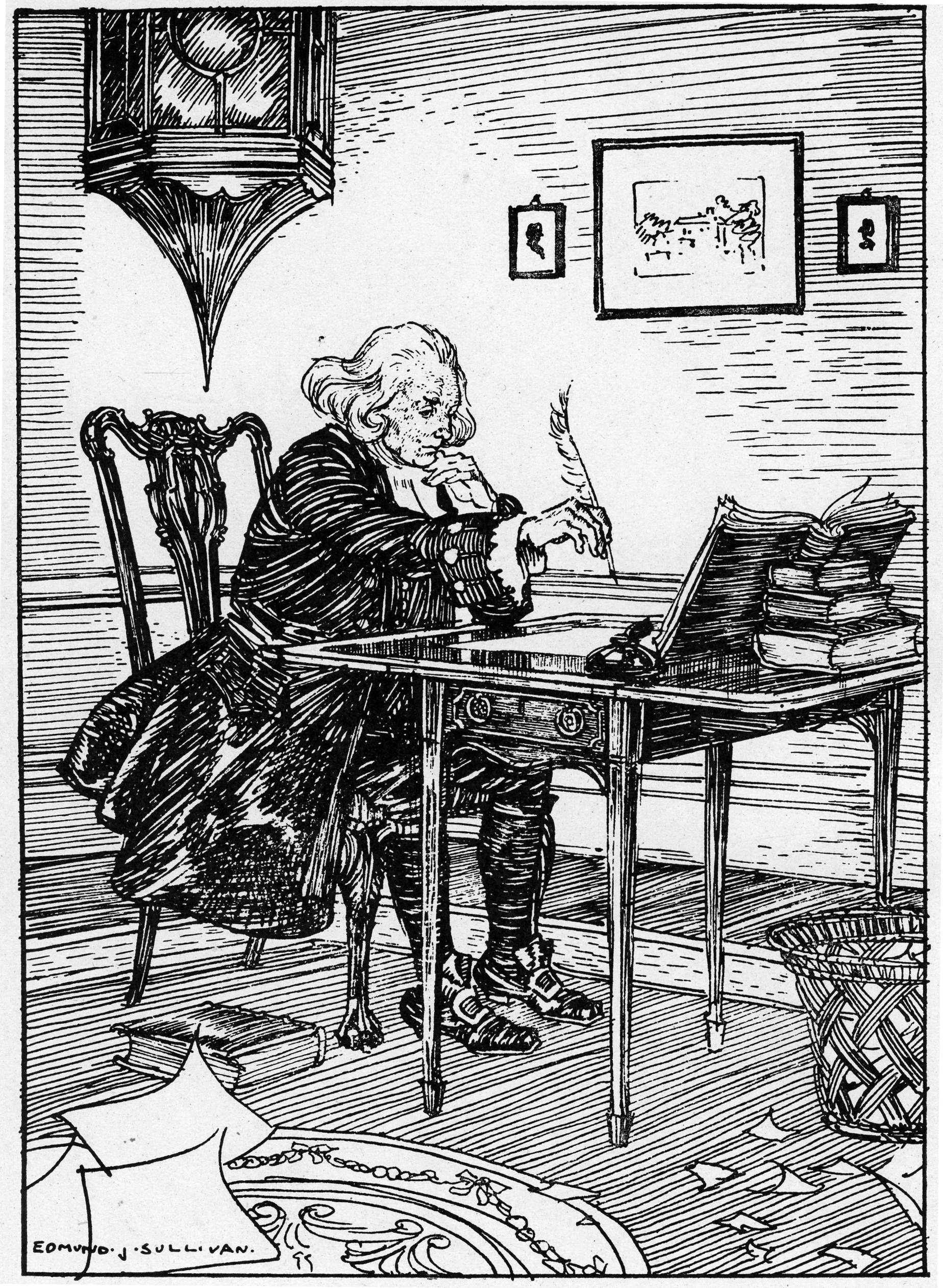

[The Author at his desk], one of Edward Sullivan's illustrations for Gilbert White's The Natural History of Selbourne.

White's interest in "nature's rude magnificence" (17), a phrase he used in one of his poems, allowed him to find endless delights in the observation of the landscape surrounding Selborne, where he was several times a curate during his career; his small village was world enough for him and provided innumerable opportunities of studying living animals in their habitats, as opposed to some contemporary scientists who exclusively worked on skeletons or caged specimens. With "the God of Nature" as his "secret guide," as he said in another poem (20), combining "scientific precision, poetic narrative and conversational anecdote" according to Simon Martin (26), White wrote a series of letters to his fellow naturalist Thomas Pennant and the Honorable Daines Barrington, which he later gathered in his Natural History and Antiquities. Since 1789, the book has gone through some 400 different editions and reissues; it influenced Darwin, among others, and in the 1930s, painter John Piper gave a copy to his future wife Myfanwy when they were courting. Not too bad for a book in which, according to Virginia Woolf, "the love interest is supplied chiefly by frogs" (88). Simon Martin also underlines how Gilbert White, who considered that all creatures had their role to play, can now help us look at "the interconnectedness of natural life" in a time of "planetary emergency" (7).

In the volume published in 1789 by White's brother Benjamin, illustrations were more topographical than biological. A large one, North East view of Selborne, from the Short Lythe. by Swiss artist Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, was folded as a frontispiece, the title page included an oval etching of the Hermit's hut above the village, and there was only one depiction of an animal, a hand-coloured print of "A Hybrid Bird." Since then, all attempts at illustrating White's work seem to have been polarized between those two possible tendencies, as shown by the various twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists whose works are reproduced in the present volume.

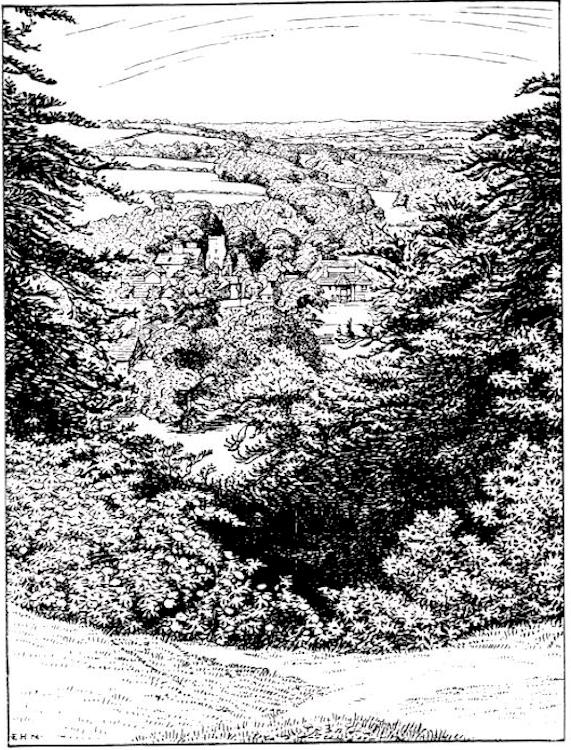

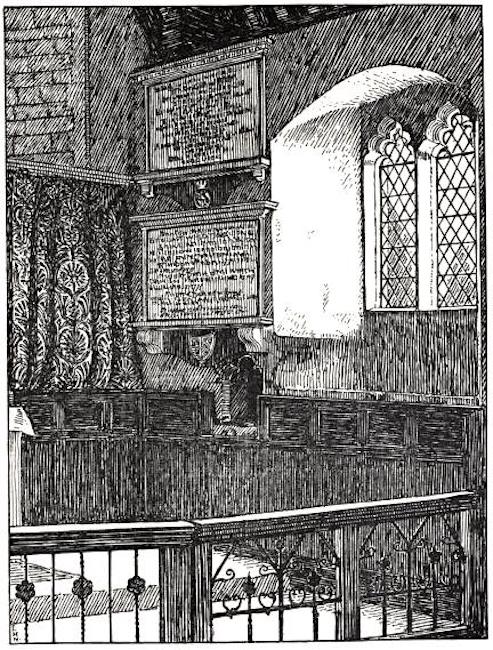

Three of Edmund Hort New's illustrations for The Natural History of Selbourne: (a) Selborne from the Hangar. (b) A View of White's House. (c) White's Monument.

A Selborne Society was founded in 1885, Britain's first national conservation organisation, reflecting a late Victorian interest for the preservation of nature; Alfred, Lord Tennyson became its president in 1888. Numerous new editions of White's book would follow. In 1900, the Bodley Head published a volume featuring illustrations by Edmund Hort New (1871-1931), who had worked for the Kelmscott Press. The charming Arts and Crafts initial letters of that volume are used in the Pallant House book, which also reproduces its cover and the landscapes illustrating various chapters, some of which are reminiscent of Millais' view of Orley Farm for Trollope's novel or John William North's "Idyllic" views of the English countryside.

In the same year, Edmund Sullivan (1860-1933) created a series of line-drawings for White's

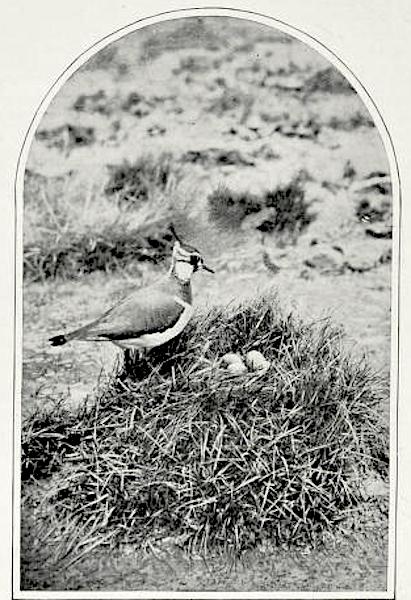

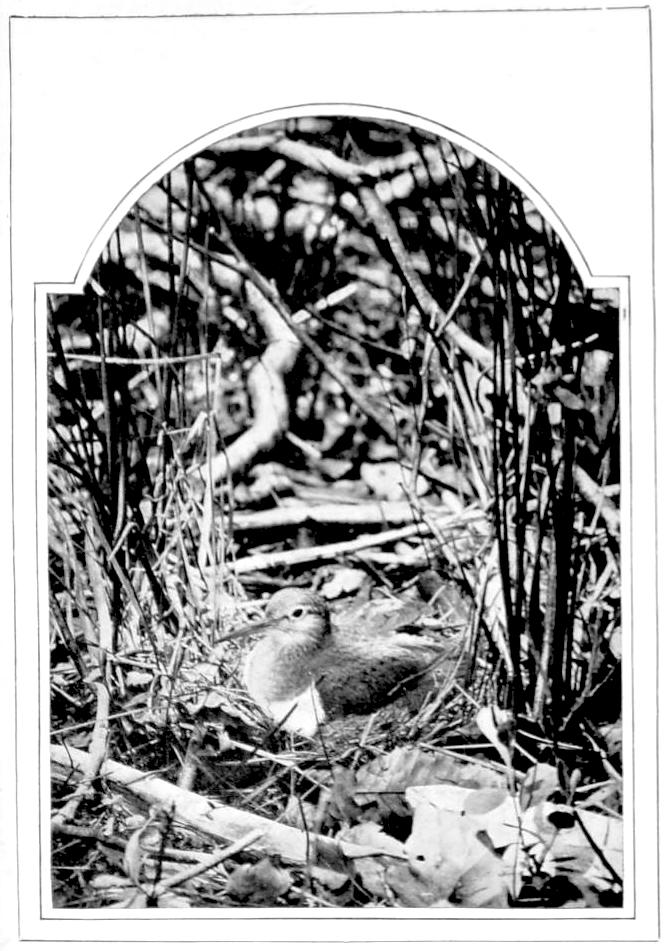

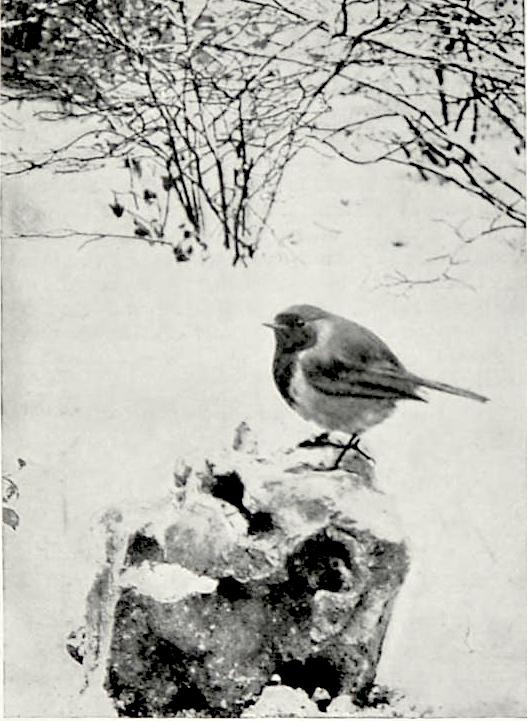

The Kearton brothers' illustrations for The Natural History of Selbourne: (a) Lapwing and Nest. (b) Sandpiper on Nest. (c) Red-Breast.

Simon Martin's first chapter (pages 23 to 85) focuses on the succession of artists who illustrated White between the 1920s and the 1990s. A distinct chapter, "The Modern Illustrators," provides bigger reproductions, without commentary, from pages 95 to 151. Some names are famous as painters, like John Piper or John Nash (younger brother of the more daring Paul Nash), others owe their reputation to wood-engraving, like Eric Ravilious, and most of them have been unjustly forgotten, like Gertrude Hermes or Claire Oldham. Some produced pictures of animals, like Eric Fitch Daglish in 1929, others preferred landscapes, like Clare Leighton, whose prints remind one of the work of American Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton.

As shown by Simon Martin in his second chapter, "each generation has found a path into the book that has relevance to their times, and (…) successive artists have brought it to their own form of expression" [153]. He himself commissioned works from eleven artists who had an affinity with nature, who were born between 1951 (Clive Hicks-Jenkins) and 1988 (Alice Pattullo), and who used various techniques – wood-engraving, linocut, collage, gouache, pencil, scraperboard, screenprint, watercolour and even sculpture – to react to White's book, representing some of the traditionally recurring subjects, like Timothy Tortoise, but also widening the scope of art's reaction to what Gilbert White called "the wonders of the Creation, too frequently overlooked as common occurrences" (85).

Links to Related Material

- Richard Jefferies and other British Nature Writers — Gilbert White, William Cobbett, and W.H. Hudson

- Victorian Ornithologists

Bibliography

Martin, Simon. Drawn to Nature: Gilbert White and the Artists. Chichester: Pallant House Gallery, distr. by Yale University Press, 2021. Hardback, 192 pp., 193 ill. ISBN 978-1-869827-75-5. £25.00

Created 9 July 2023