Commentary: 'Timothy Sparks' Attacks the Promotion of Strict Observance of the Sabbath

Chapman, probably impressed by the Gilpin engraving [by Phiz], had already approached the young artist to supply the designs for the woodcuts to illustrate Dickens' squib, Sunday Under Three Heads, which Chapman published anonymously in 1836. [Buchanan-Browne, 11]

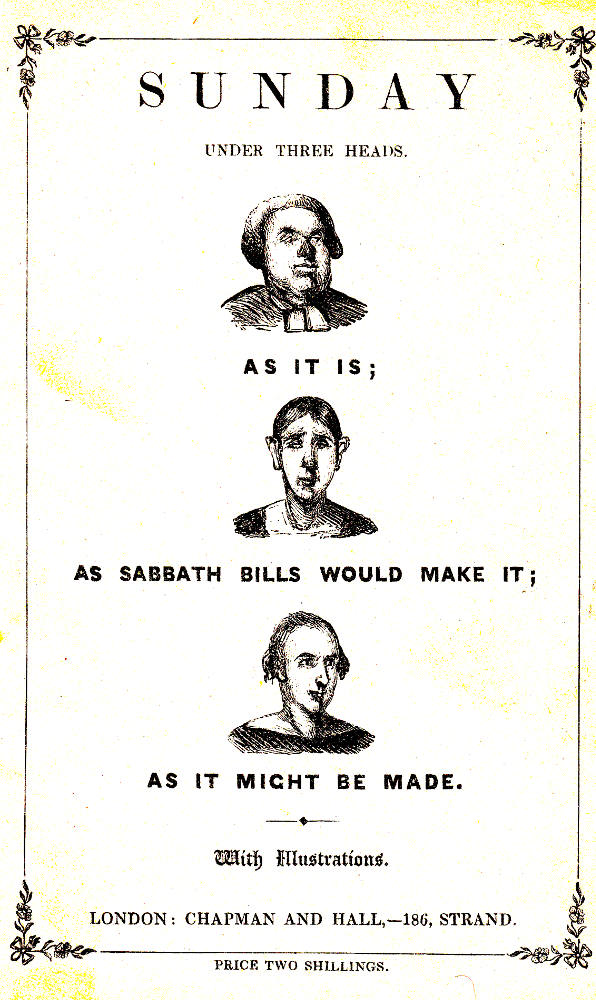

Left: The initial Phiz illustration for the 1836 pamphlet: Sunday Under Three Heads, the original Chapman and Hall cover for the two-shilling pamphlet.

Assailing The Lord's Day Act, otherwise, "Sunday Observance Legislation," twenty-four-year-old short-hand writer Charles Dickens decided to issue the thirty-six-page anti-sabbatarian tract under a pseudonym, "Timothy Sparks." The bill was sponsored by a Scottish MP, Sir Andrew Agnew (1793-1849), Member of Parliament for Wigtonshire, on behalf of the Society for Promoting Due Observance of the Lord's Day, founded in 1831. The group's agitation for legislation resulted in parliamentary bills in 1833, 1834, and 1837. Siding on the question with such radicals as William Corbett and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Dickens rightly regarded the proposed legislation as a hypocritical attempt on the part of the well-to-do to forbid innocent amusements among the working class on their one day off. Dickens ironically dedicated the pamphlet to Charles Bloomfield (1786-1857), Bishop of London (who is likely the first "head" at the top of the page).

The pamphlet's illustrator, unknown to Dickens at the time except through occasional illustrations in Chapman and Hall's Library of Fiction, would be the twenty-one-year-old Hablot Knight Browne. Frederick Chapman commissioned Browne to provide an illustrated title-page and three full-page wood-engravings for Sunday Under Three Heads — As it is; as Sabbath Bills would make it; as it might be made. Dickens's was one of those Liberal and Radical Reform voices who spoke up against the Bishop of London and other extreme Sabbatarians such as Sir Andrew Agnew, sponsor of the bill to deny recreation to the working classes on their only day off. "To believe that Dickens and Phiz were still unacquainted at the time the pamphlet was written seems myopic" (Lester, 41). Undoubtedly the reforming journalist of Sketches by Boz (First Series: February 1836) and the visual satirist both believed that such legislation would deprive the poor of meat for the Sunday meal and a day's healthful recreation in the parks and on the river. The labouring masses of the metropolis would thus become restless, discontented, and fractious. "Sunday might be made a time when museums were open in the afternoon and when games and outdoor recreations, like those the author had once seen sponsored by a country clergyman, which engaged the whole community in healthful activity" (Davis, 371).

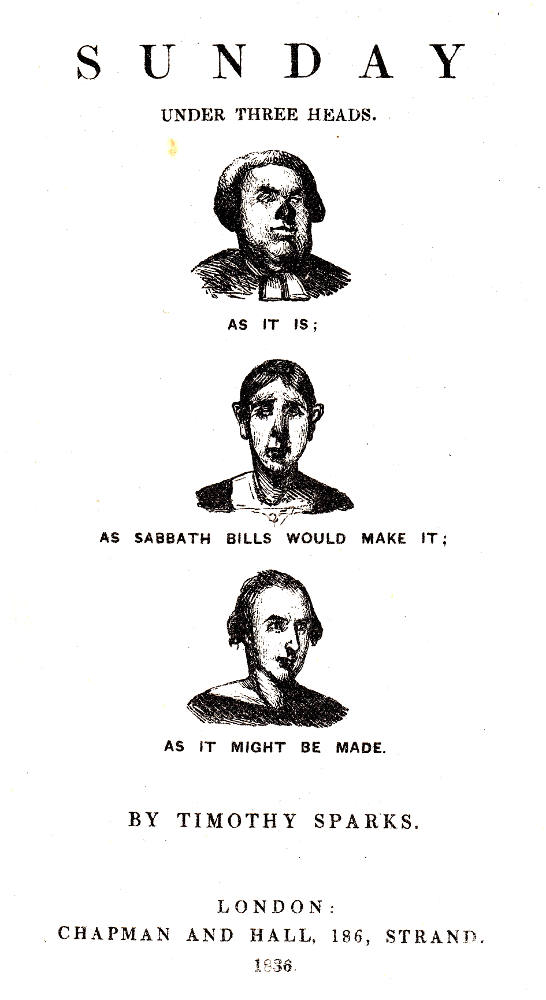

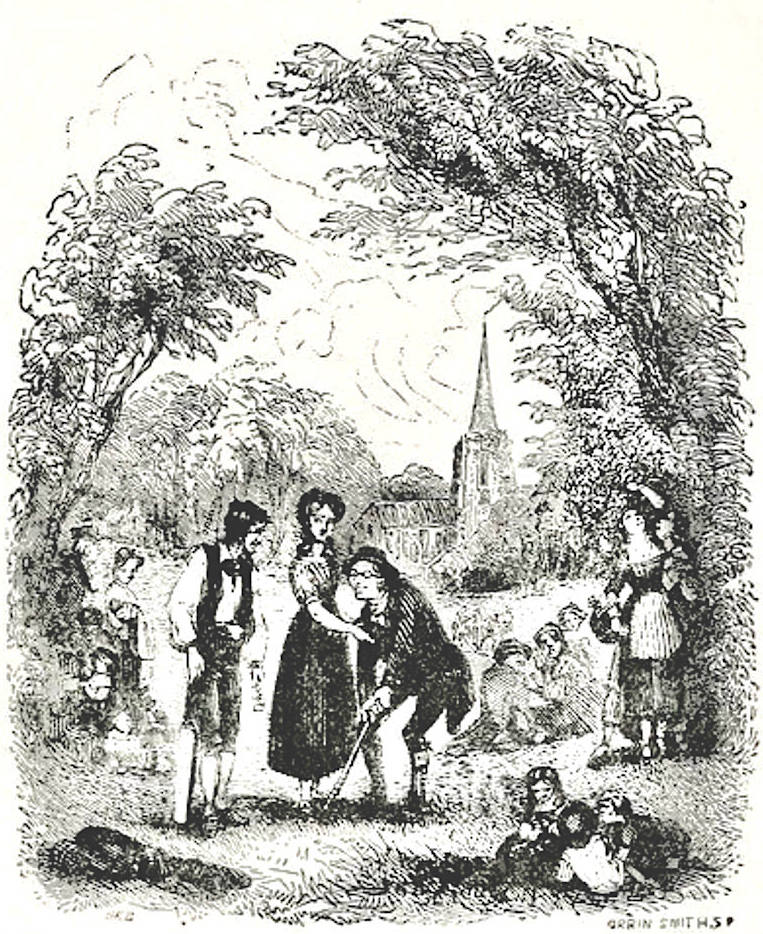

Right: The unframed Phiz title-page for the pamphlet by "Timothy Sparks": Sunday Under Three Heads, London: Chapman and Hall, 186, Strand, June 1836.

Michael Slater explains Dickens's use of a pseudonym as already he had something of a following among London readers as the "Boz" of the Sketches and did not wish to mar his reputation for genial observance with a piece of crusading journalism. But he could not contain his indignation At the proposed sabbatarian legislation, for "it was defeated by only thirty-two votes" (Slater 70) in the Commons on May 18. "Presumably Dickens did not want Boz to seem too openly polemical at this time when he was still gathering his audience and carefully cultivating 'an excellent character as a quiet, modest fellow' (reviewers praising the 'good sense' of this little work clearly had no idea that it was the work of Boz)" (Slater 71). Its organization, notes Slater, is ironically suggestive of the typical Anglican sermon, as the full title suggests the three 'heads' of an argument delivered from an Anglican pulpit.

- Illustrated Title vignettes: The Three Heads — As It Is; As Sabbath Bills Would Make It; As It Might Be made.

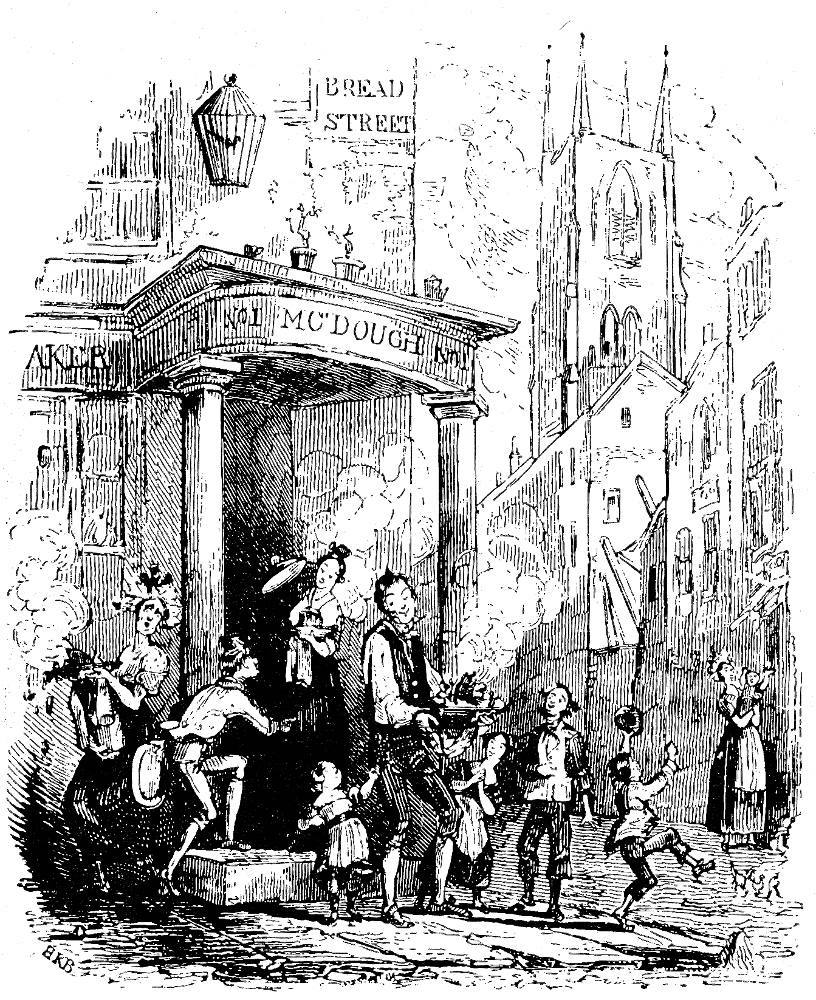

- Sunday as it is: Bread Street

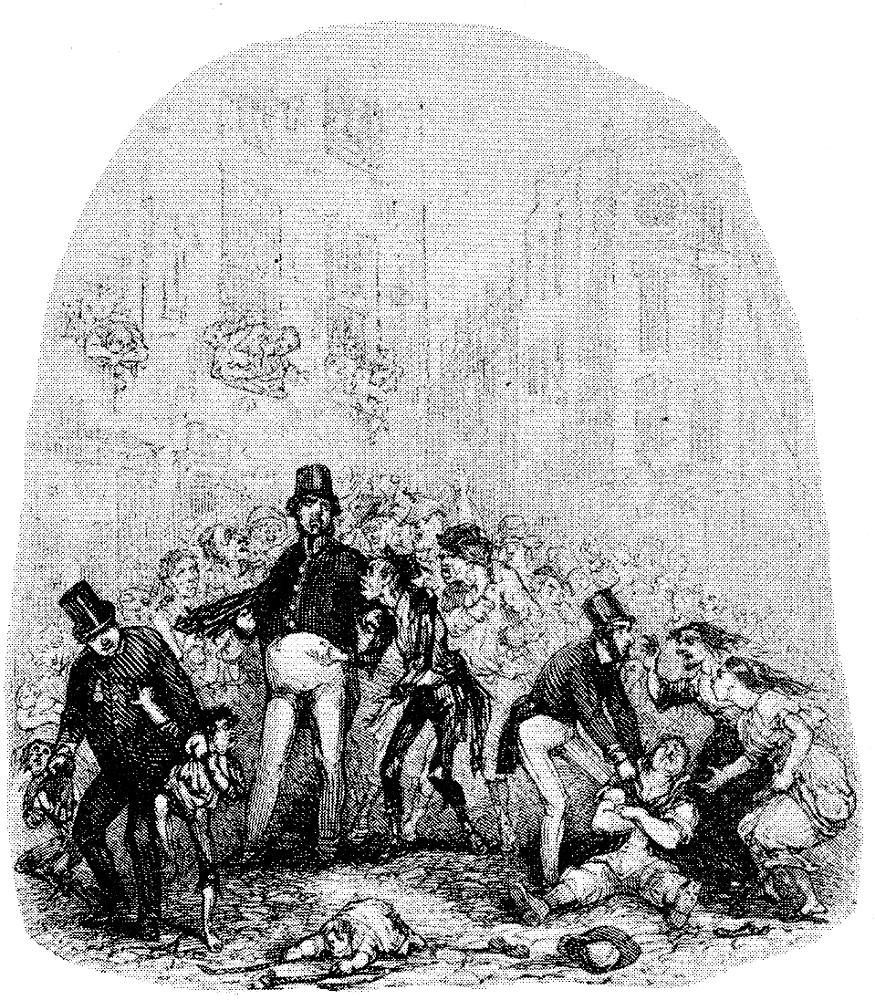

- Sunday as Sabbath Bills would make it

- Sunday as it might be made.

Michael Steig's Comments from Dickens and Phiz (1978)

The first collaboration between Dickens and Browne was on something considerably less than a novel, but it clearly shows their joint debt to the Hogarthian tradition (since both Sunday Under Three Heads and the fourth part of Pickwick, for which Browne was engaged, were published in June 1836, the order of events is not certain.). The first two of the three small wood engravings for the anti-Sabbatarian pamphlet Sunday Under Three Heads demonstrate the complementary nature of Browne's and Dickens's art, for they make explicit a quality which is only latent in the text. Dickens conceived his tendentious pamphlet in the mode of Hogarth's Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751), posing alternative consequences which will result from two opposed ways of ordering British society. The immediate occasion of Hogarth's pair of engravings was a measure to limit the sale of gin (Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works, 1, p. 207), while Dickens was concerned with the repressive Sabbath Bills, but both men present contrasts of healthy and depraved London life. Dickens mentions beer often enough in the first essay to make reasonable the connection with Hogarth's plates; for the drinking of beer "in content and comfort" is clearly contrasted with "outward signs of profligacy or debauchery." (Sunday Under Three Heads, in The Nonesuch Dickens, 23 vols. (London: Nonesuch Press, 1938), 22: 507). Although the second essay does not mention the beer which is earlier associated with innocent recreation, it predicts that the restrictive Sabbath laws will produce much more profligacy, idleness, drunkenness, and vice." (Ibid., p. 516.)

Left: Phiz's scene for Sunday As It Is. Centre: Phiz's prophetic scene of constables restraining an unruly, drunken mob in the streets near the London docks in Sunday As Sabbath Bills Would Make It. Right: A churchyard idyll on a Sunday afternoon with the extended working-class enjoying recreation together: Sunday As It Might Be Made (1836).

Despite their technical weakness, the two cuts illustrating these two essays make evident the twenty-one-year-old Browne's maturity as an interpreter of the moral significance of his author's text. In particular they make use of iconographic techniques developed by Hogarth and his followers, especially emblematic detail — the church, the clock, and the inscription ("Bread Street") — to underline certain implications of the text. These sorts of devices are employed by Browne in every Dickens novel he illustrated through Little Dorrit (as well as in many by other authors), and they increase in frequency from Pickwick on, reaching a high point in Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son, and David Copperfield, then diminishing in Bleak House and Little Dorrit, and disappearing entirely from the sixteen illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities. The particular categories of emblematic detail are various, from biblical allusions to titles of plays, sculptures or pictures representing classical mythology, references to Hogarth and Aesop, book titles of various kinds, and fairly standard emblematic objects such as clocks, cobwebs (usually indicating that the hero is somehow trapped, like a fly), maps, pictures of ships sailing smoothly or sinking — the list is almost endless. [Steig, Chapter One, "Illustration, Collaboration, and Iconography," pp. 12-13]

Scanned images, first commentary and formatting by Philip V. Allingham. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Buchanan-Browne, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1978.

Davis, Paul. "Sunday under Three Heads." Charles Dickens A top Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998. 371.

Dickens, Charles. Sunday Under Three Heads. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablột Knight Browne]. In One Vol. Project Gutenberg. Last Updated: August 19, 2024. Rpt.London: J. W. Jarvis & Son, 28, King William Street, Strand, 1 February 1884. Pp. v + 49.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Chapter Six, "The Collaborators." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 39-51.

Slater, Michael. Chapter 4: "Break-through Year: 1836." Charles Dickens. London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. Pp. 59-83.

Sparks, Timothy. [Charles Dickens] Sunday Under Three Heads — As it is; as Sabbath Bills would make it; as it might be made. London: Chapman and Hall, 1836.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978.

"Sunday Under Three Heads: An Example of Early Social Activism by Charles Dickens." 30 March 2021. DickensLit.com: Charles Dickens Online.

Created 30 September 2024

last modified 16 October 2024