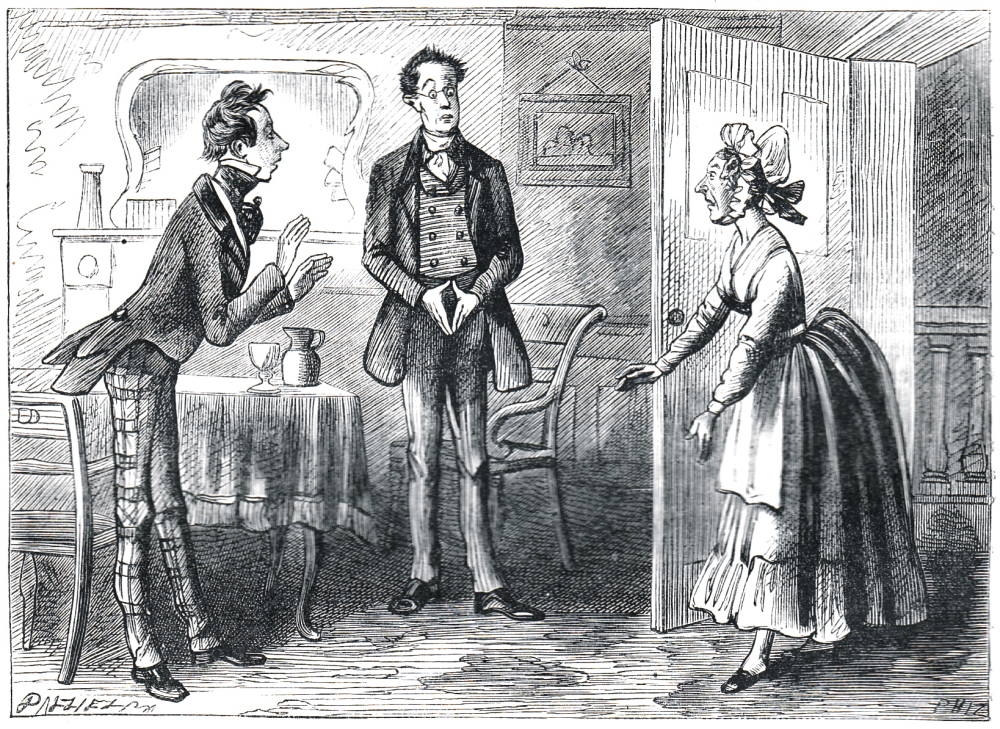

A little fierce woman bounced into the room, all in a tremble with passion, and pale with rage by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, p. 217. Engraved by one of the Dalziels. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The bachelor-medical students' landlady, a real Dickensian Cockney "character" with a distinctive voice, Mrs. Mary Ann Raddle, interrogates Bob Sawyer about when he will be paying his bill for his Lant Street rooms in the Borough. (The area had special significance for Dickens since he lodged here while working at Warren's Blacking in 1822-23.) Predictably, Bob prevaricates in a Micawberesque manner, and Mrs. Raddle remonstrates with him, although in her neighbourhood, as Dickens explains at the head of chapter 32, "The population is migratory" and "the rents are dubious" (216), so that she ought to be used to such attempts on the part of her renters to put off her requests. Bob is instantly recognisable by his checked trousers and wild haircut.

Passage realised

"Please, Mister Sawyer, Missis Raddle wants to speak to you."

Before Mr. Bob Sawyer could return any answer, the girl suddenly disappeared with a jerk, as if somebody had given her a violent pull behind; this mysterious exit was no sooner accomplished, than there was another tap at the door — a smart, pointed tap, which seemed to say, "Here I am, and in I'm coming."

"Mr. Bob Sawyer glanced at his friend with a look of abject apprehension, and once more cried, "Come in."

The permission was not at all necessary, for, before Mr. Bob Sawyer had uttered the words, a little, fierce woman bounced into the room, all in a tremble with passion, and pale with rage.

"Now, Mr. Sawyer," said the little, fierce woman, trying to appear very calm, "if you'll have the kindness to settle that little bill of mine I'll thank you, because I've got my rent to pay this afternoon, and my landlord's a-waiting below now." Here the little woman rubbed her hands, and looked steadily over Mr. Bob Sawyer's head, at the wall behind him.

"I am very sorry to put you to any inconvenience, Mrs. Raddle," said Bob Sawyer deferentially, 'but —"

"Oh, it isn't any inconvenience," replied the little woman, with a shrill titter. "I didn't want it particular before to-day; leastways, as it has to go to my landlord directly, it was as well for you to keep it as me. You promised me this afternoon, Mr. Sawyer, and every gentleman as has ever lived here, has kept his word, Sir, as of course anybody as calls himself a gentleman does.' Mrs. Raddle tossed her head, bit her lips, rubbed her hands harder, and looked at the wall more steadily than ever. It was plain to see, as Mr. Bob Sawyer remarked in a style of Eastern allegory on a subsequent occasion, that she was 'getting the steam up."

"I am very sorry, Mrs. Raddle," said Bob Sawyer, with all imaginable humility, "but the fact is, that I have been disappointed in the City to-day." — Extraordinary place that City. An astonishing number of men always are getting disappointed there.

"Well, Mr. Sawyer," said Mrs. Raddle, planting herself firmly on a purple cauliflower in the Kidderminster carpet, "and what's that to me, sir?"

"I — I — have no doubt, Mrs. Raddle," said Bob Sawyer, blinking this last question, "that before the middle of next week we shall be able to set ourselves quite square, and go on, on a better system, afterwards."

This was all Mrs. Raddle wanted. She had bustled up to the apartment of the unlucky Bob Sawyer, so bent upon going into a passion, that, in all probability, payment would have rather disappointed her than otherwise. She was in excellent order for a little relaxation of the kind, having just exchanged a few introductory compliments with Mr. R. in the front kitchen.

"Do you suppose, Mr. Sawyer," said Mrs. Raddle, elevating her voice for the information of the neighbours — "do you suppose that I'm a-going day after day to let a fellar occupy my lodgings as never thinks of paying his rent, nor even the very money laid out for the fresh butter and lump sugar that's bought for his breakfast, and the very milk that's took in, at the street door? Do you suppose a hard-working and industrious woman as has lived in this street for twenty year (ten year over the way, and nine year and three-quarters in this very house) has nothing else to do but to work herself to death after a parcel of lazy idle fellars, that are always smoking and drinking, and lounging, when they ought to be glad to turn their hands to anything that would help 'em to pay their bills? Do you — —"

"My good soul," interposed Mr. Benjamin Allen soothingly.

"Have the goodness to keep your observashuns to yourself, sir, I beg," said Mrs. Raddle, suddenly arresting the rapid torrent of her speech, and addressing the third party with impressive slowness and solemnity. "I am not aweer, sir, that you have any right to address your conversation to me. I don't think I let these apartments to you, sir."

"No, you certainly did not," said Mr. Benjamin Allen.

"Very good, sir," responded Mrs. Raddle, with lofty politeness. "Then p'raps, sir, you'll confine yourself to breaking the arms and legs of the poor people in the hospitals, and keep yourself to yourself, sir, or there may be some persons here as will make you, sir." [Chapter 32, p. 218 in the Chapman & Hall Household Edition]

In revisiting the misadventures of the medical students (later turned apothecaries) in his 1873 woodcuts, Phiz has made the irrepressible Bob Sawyer perhaps a little too angular and stick-like in his figure, and Mrs. Raddle (a premonitory rumble of Mrs. Sairey Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit) not quite forceful or "fierce" enough, and certainly not the force of nature that her voice implies. Plausibly, however, the timid Ben Allen is caught between the two of them, and between Ben and Bob Phiz has strategically positioned a rather small white jug (which will be a receptacle for punch) and a single large goblet (of the type borrowed in quantity from the nearby public house), signifying their hedonistic, bachelor life-style. The tray full of glasses from the nearby public house and the stove on which the punch is warming are nowhere in sight, nor is Mrs. Raddle rubbing her hands in anticipation of receiving her rent and "getting her steam up" (218). More disappointingly, Phiz has not taken the opportunity to incorporate any of the details of the setting, in particular, "the preparations for the reception of visitors" (216), as provided by Dickens.

“Get along with you, you old wretch!”

In the other Household Edition, that issued by Harper and Brothers, New York, Thomas Nast realised a moment from later in the same chapter when Mrs. Raddle, still upset with Bob for not paying his rent, throws the bacchanal celebrants out of her house in the wee hours after their carousing has led to drunken revelry and singing. Snodgrass and Winkle are on the landing, while Tupman (above) and Pickwick (centre foreground) are already making their way down the staircase as Mrs. Raddle (just visible above the railing, upper centre) denounces the departing bachelors as "brutes" (Harper & Bros. Household Edition, p. 191). The lateness of the hour is suggested by the enormous shadows of Pickwick and Tupman on the wall of stairwell (right). The number of revellers suddenly entreated to depart by the anxious Bob is implied by the number of hats visible in the open doorway (left), but one receives very little sense of either the characters or the setting in Nast's plate, which fails to capture the humorous aspect of the episode, which Nast has us view from a perspective opposite the bottom of the stairs, Bob Sawyer's apartment being one flight up (on "the first-floor," as the servant-girl tells Pickwick as he arrived earlier):

"Mr. Sawyer! Mr. Sawyer!" screamed a voice from the two-pair landing.

"It's my landlady," said Bob Sawyer, looking round him with great dismay. "Yes, Mrs. Raddle."

"What do you mean by this, Mr. Sawyer?" replied the voice, with great shrillness and rapidity of utterance. "Ain't it enough to be swindled out of one's rent, and money lent out of pocket besides, and abused and insulted by your friends that dares to call themselves men, without having the house turned out of the window, and noise enough made to bring the fire-engines here, at two o'clock in the morning? — Turn them wretches away."

"You ought to be ashamed of yourselves," said the voice of Mr. Raddle, which appeared to proceed from beneath some distant bed-clothes.

"Ashamed of themselves!" said Mrs. Raddle. "Why don't you go down and knock 'em every one downstairs? You would if you was a man."

"I should if I was a dozen men, my dear," replied Mr. Raddle pacifically, "but they have the advantage of me in numbers, my dear."

"Ugh, you coward!" replied Mrs. Raddle, with supreme contempt. "Do you mean to turn them wretches out, or not, Mr. Sawyer?"

"They're going, Mrs. Raddle, they're going," said the miserable Bob. "I am afraid you'd better go," said Mr. Bob Sawyer to his friends. "I thought you were making too much noise."

"It's a very unfortunate thing," said the prim man. "Just as we were getting so comfortable too!" The prim man was just beginning to have a dawning recollection of the story he had forgotten.

"It's hardly to be borne," said the prim man, looking round. "Hardly to be borne, is it?"

"Not to be endured," replied Jack Hopkins; "let's have the other verse, Bob. Come, here goes!"

"No, no, Jack, don't," interposed Bob Sawyer; "it's a capital song, but I am afraid we had better not have the other verse. They are very violent people, the people of the house."

"Shall I step upstairs, and pitch into the landlord?" inquired Hopkins, "or keep on ringing the bell, or go and groan on the staircase? You may command me, Bob."

"I am very much indebted to you for your friendship and good-nature, Hopkins," said the wretched Mr. Bob Sawyer, "but I think the best plan to avoid any further dispute is for us to break up at once."

"Now, Mr. Sawyer," screamed the shrill voice of Mrs. Raddle, "are them brutes going?"

"They're only looking for their hats, Mrs. Raddle,' said Bob; 'they are going directly."

"Going!" said Mrs. Raddle, thrusting her nightcap over the banisters just as Mr. Pickwick, followed by Mr. Tupman, emerged from the sitting-room. "Going! what did they ever come for?"

"My dear ma'am,' remonstrated Mr. Pickwick, looking up.

"Get along with you, old wretch!" replied Mrs. Raddle, hastily withdrawing the nightcap. "Old enough to be his grandfather, you willin! You're worse than any of 'em."

Mr. Pickwick found it in vain to protest his innocence, so hurried downstairs into the street, whither he was closely followed by Mr. Tupman, Mr. Winkle, and Mr. Snodgrass. Mr. Ben Allen. . . . [Harper & Brothers' Household Edition, p. 191-192]

Related Material

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. Formatting by George P. Landow. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874; New York: Harpers, 1874.

Last modified 5 April 2012