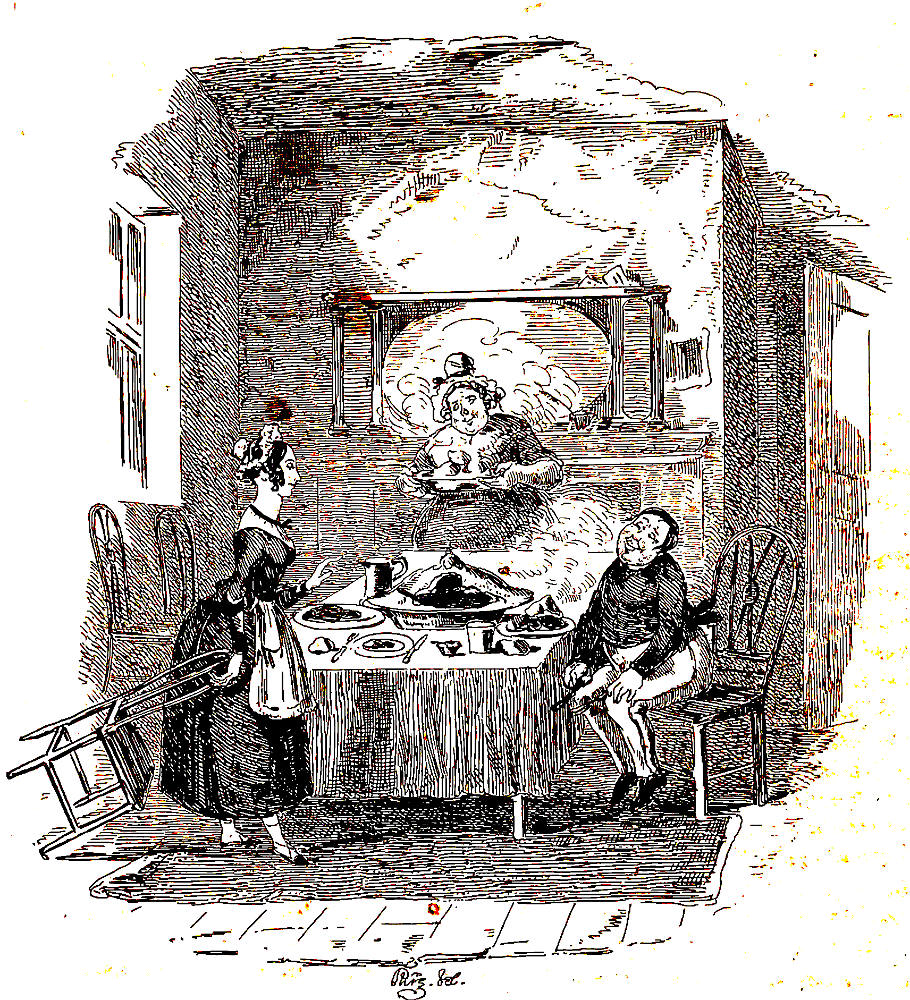

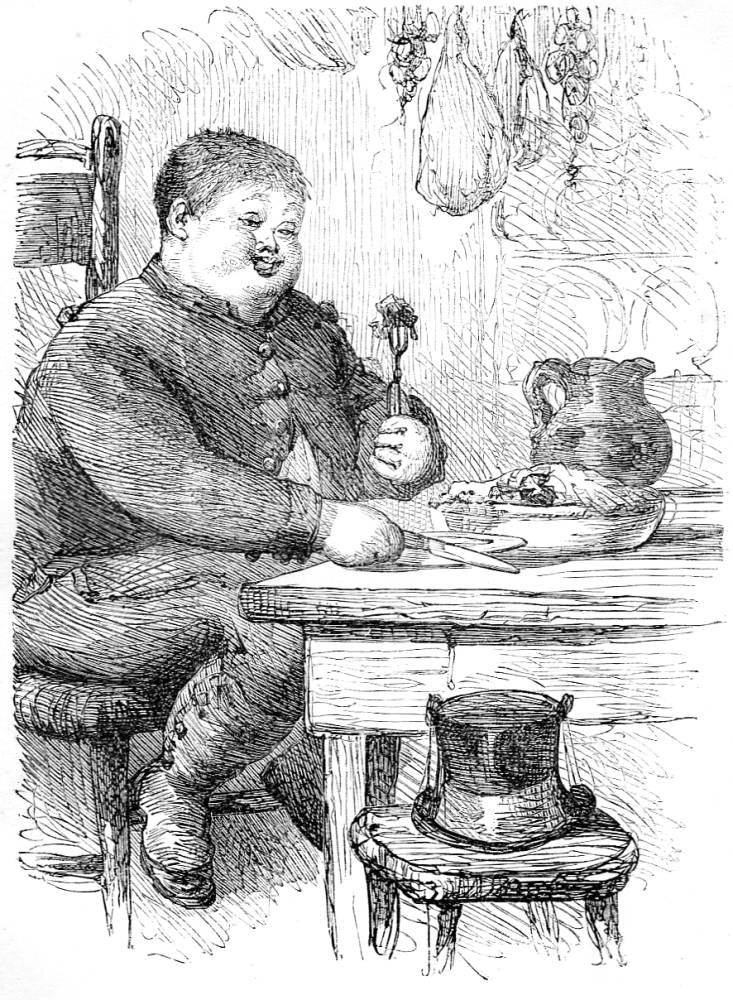

Mary and The Fat Boy; or, The Fat Boy and Mary (Nos. 19 and 20) — fortieth steel engraving for Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club; two versions by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) for the November 1837 (final monthly) number and the 1838 bound volume; Chapter LIV, “Containing some Particulars relative to the double Knock, and other Matters, among which certain Interesting Disclosures relative to Mr. Snodgrass and a Young Lady are by no means irrelevant to this History,” facing page 579. The original illustration is 10.5 cm high by 10.5 cm wide (4 inches), vignetted. In the initial or A engraving of Plate 40, as Johannsen (1956) notes, the knife held by the Fat Boy "points downwards" (69) and "There is a saltcellar on the table between the knife and the tumbler, and the pitcher is not shaded on the left side" (69). In Plate B3, used in the 1838 bound volume, after "Phiz, del the legend has been engraved. Otherwise, Johannsen accounts for the differences in the B or serial plates as the consequence of retouching during production rather re-engraving: "The fainter lines of the retouched Plate B2 are identical with the shade lines of the original B" (69). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Details

Passage Illustrated: Consuming Feminine Pulchritude

'He understands us, I see," said Arabella. 'He had better have something to eat, immediately," remarked Emily.

The fat boy almost laughed again when he heard this suggestion. Mary, after a little more whispering, tripped forth from the group, and said:

"I am going to dine with you to-day, sir, if you have no objection."

"This way," said the fat boy eagerly. "There is such a jolly meat-pie!"

With these words, the fat boy led the way downstairs; his pretty companion captivating all the waiters and angering all the chambermaids as she followed him to the eating-room.

There was the meat-pie of which the youth had spoken so feelingly, and there were, moreover, a steak, and a dish of potatoes, and a pot of porter.

"Sit down," said the fat boy. "Oh, my eye, how prime! I am so hungry."

Having apostrophised his eye, in a species of rapture, five or six times, the youth took the head of the little table, and Mary seated herself at the bottom.

"Will you have some of this?" said the fat boy, plunging into the pie up to the very ferules of the knife and fork.

"A little, if you please," replied Mary.

The fat boy assisted Mary to a little, and himself to a great deal, and was just going to begin eating when he suddenly laid down his knife and fork, leaned forward in his chair, and letting his hands, with the knife and fork in them, fall on his knees, said, very slowly —

"I say! How nice you look!"

This was said in an admiring manner, and was, so far, gratifying; but still there was enough of the cannibal in the young gentleman's eyes to render the compliment a double one.

"Dear me, Joseph," said Mary, affecting to blush, "what do you mean?" [Chapter LIV, “Containing some Particulars relative to the double Knock, and other Matters, among which certain Interesting Disclosures relative to Mr. Snodgrass and a Young Lady are by no means irrelevant to this History,” 579]

Commentary: Joe, having been fed, grows amorous

Although Shakespeare in Twelfth Night described music as "the food of love," in this illustration of Wardle's chubby, omnivorous page (denominated the "Fat Boy") and the charming maid Mary, the food of love is apparently . . . food. That the Fat Boy should suddenly make an amorous advance upon the fetching maid may be another result of his suffering from Kleine-Levin syndrome (Guiliano and Collins, 508), an interpretation supported by Dickens's alluding to Joe in Chapter VIII as "the infant Lambert," for Daniel Lambert at his death 1809 weighed 739 lbs. Previously seen in one of Phiz's earliest plates for the novel, The fat boy awake on this occasion only (Chapter VIII), the chubby page from Dingley Dell is now the focus of an illustration as the power of sexual attraction overwhelms his gormandising. Thus, Phiz extends the reader's sympathy to a character formerly a mere stereotype, and makes him worthy of the reader's interest as the writer pulls together the multiple and various threads of the extremely loose picaresque plot.

The Fat Boy's libido seems to have been stimulated by the feast as he oggles the comely maid. In Phiz's illustration, the narcoleptic page is suddenly alert to the wasp-waisted maid's charms, proof, perhaps, that opposites attract. Captivated by her demeanour as well as her slender form, Joe actually neglects the gigantic pie in the midst of the table, and is even oblivious to the enormous portion he has just cut himself. He does not even notice the corpulent cook's carrying in a loaded platter (up centre), a detail that Dickens does not give in the text. Phiz's comment or implied visual comment on human nature is encapsulated in the corpulent lady who is providing yet more comestibles for the omnivorous servant: what she is, perhaps, in time ("col tempo") Mary herself will become if she participates in satisfying Joe's appetites.

Moreover, Phiz has overturned Mary's chair so that its back points both towards the feast and the entranced Fat Boy. As she moves towards him, she raises her right hand in admonishment. Joe lowers his eating utensils in order to consume visually Mary's shapely beauty, a delicate contrast to his own corpulence.

The Scenes with The Fat Boy in Other Editions (1837-74)

Left: HGarry Furniss seems to have had Phiz's original engraving in mind as he emphasized Joe's awkward lasciviousness in Mary and the Fat Boy: The fat boy, with elephantine playfulness, stretched out his arms to ravish a kiss Mary and The Fat Boy (1910). Centre: Phiz's Household Edition woodcut reworks his original 1837 steel engraving as "I say, how nice you look!" (1874). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Vol. 1 illustration The Fat Boy (1867) makes Joe a grossly overweight child. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Phiz's original engraving for the conclusion of the serial novel, The Fat Boy Awake Again (substituted in November 1837 for Chapter VIII). Centre: Thomas Nast's American Household Edition woodcut reworks Phiz's 1837 steel engraving as "Will you have some of this?" said the Fat Boy (1873). Right: Harry Furniss's version of the scene between Mary and the suddenly amorous Joe, Mary and the Fat Boy (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens.2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Johnannsen, Albert. "The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club." Phiz Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1956. Pp. 1-74.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Created 15 January 2012

Last updated 3 April 2024