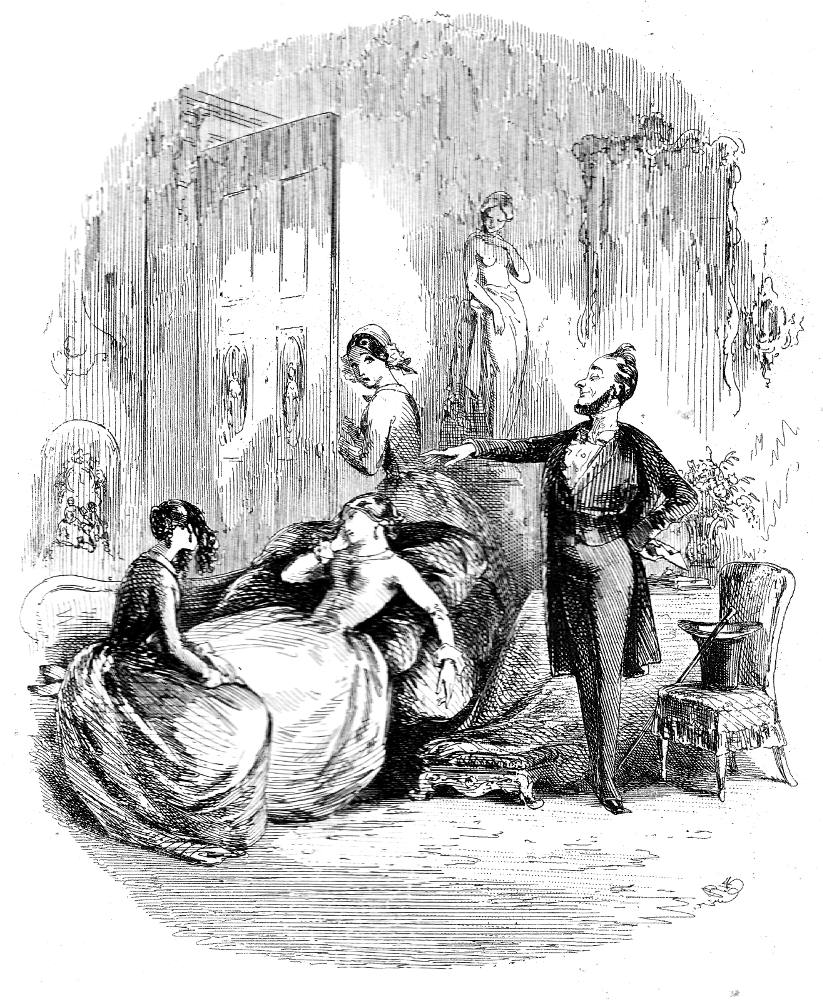

The Mesmeric Trance

Phiz

Engraver: Dalziels

1852

Vignette: 13.2 cm by 11.2 cm (5 ⅛ by 4 ⅜ inches)

Steel-engraving

Charles Lever's The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life, Chapter XXVI, "The End of the First Act," facing p. 209.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, sizing, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: A Medical Application of Hypnosis

The whole temper of the letter was feeling and tender. Without even in the most remote way adverting to what had occurred between Lady Hester and himself, he spoke of their separation simply in its relation to Kate Dalton, for whom they were both bound to think and act with caution. As if concentrating every thought upon her, he did not suffer any other consideration to interfere. Kate, and Kate only, was all its theme.

Lady Hester, however, read the lines in a very different spirit. She had just recovered from a mesmeric trance, into which, to calm her nervous exaltation, her physician, Dr. Buccellini, had thrown her. She had been lying in a state of half-hysterical apathy for some hours, all volition, almost all vitality, suspended, under the influence of an exaggerated credulity, when the letter was laid upon the table.

“What is that your maid has just left out of her hand?” asked the doctor, in a tone of semi-imperiousness.

“A letter, a sealed letter,” replied she, mystically waving her hand before her half-closed eyes.

The doctor gave a look of triumph at the bystanders, and went on:

“Has the letter come from a distant country, or from a correspondent near at hand?”

“Near!” said she, with a shudder.

“Where is the writer at this moment?” asked he.

“I now take the letter in my hand,” said the doctor, “and what am I looking at?”

“A seal with two griffins supporting a spur.”

The doctor showed the letter on every side, with a proud and commanding gesture. “There is a name written in the corner of the letter, beneath the address. Do you know that name?”

A heavy, thick sob was the reply.

“There there be calm, be still,” said he, majestically motioning with both hands towards her; and she immediately became composed and tranquil. “Are the contents of this letter such as will give you pleasure?”

A shake of the head was the answer.

“Are they painful?”

“Very painful,” said she, pressing her hand to her temples.

“Will these tidings be productive of grand consequences?”

“Yes, yes!” cried she, eagerly.

“What will you do, when you read them?”

“Act!” ejaculated she, solemnly.

“In compliance with the spirit, or in rejection?”

“Rejection!”

“Sleep on, sleep on,” said the doctor, with a wave of his hand; and, as he spoke, her head drooped, her arm fell listlessly down, and her long and heavy breathing denoted deep slumber. “There are people, Miss Dalton,” said he to Kate, “who affect to see nothing in mesmerism but deception and trick, whose philosophy teaches them to discredit all that they cannot comprehend. I trust you may never be of this number.” [Chapter XXVI, "The End of the First Act," pp. 208-209]

Commentary: Lever injects Mesmerism into Lady Hester's Backstory

George Du Maurier's characterizations of the evil-eyed Svengali in Trilby in Harper's New Monthly Magazine (1894).

Phiz's depiction of the bearded, somewhat Satanic mesmerist, Lady Hester's personal physician, Dr. Buccellini, curiously anticipates that of the arch-seducer of George Du Maurier's novel Trilby (1894), the devilish mesmerist Svengali. Du Maurier's exploitative hypnotist employs the "science" of Animal Magnetism or Mesmerism to turn an unmusical Irish girl into an operatic sensation in such scenes as "Himmel! The roof of your mouth!" (February 1894). In fact, when Phiz was working on these Lever illustrations Wilkie Collins published a lengthy non-fiction discussion of medical applications of mesmerism in Magnetic Evenings at Home in The Leader (January through April, 1852), a series of six accounts of mesmerism and clairvoyance witnessed by Collins himself in January 1852 when he visited friends at the seaside spa of Weston-super-Mare, Somerset. In 1857, Collins performed alongside his friend and mentor Charles Dickens in Elizabeth Inchbald's play Animal Magnetism. In short, mesmerism or animal magnetism was much in vogue in the 1850s, and would acquire psycho-sexual nuances in the immensely popular Sensation Fiction of the 1860s.

Related Material

- Mesmerism, Madness and Witchcraft in Charlotte's Bronte's Jane Eyre

- [Review of] That Devil's Trick: Hypnotism and the Victorian Imagination, by William Hughes

- D. Stiff's Ellen Monroe acts as a mesmerized clairvoyant (1843)

- The Sensational Use of Medicine

- The Victorian Sensation Novel, 1860-1880 — "preaching to the nerves instead of the judgment"

Bibliography

Brown, John Buchanan. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1978.

Downey, Edmund. Charles Lever: His Life in Letters. 2 vols. London; William Blackwood, 1906.

Fitzpatrick, W. J. The Life of Charles Lever. London: Downey, 1901.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1852, rpt. 1872.

Lever, Charles James. The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life. http://www.gutenberg.org//files/32061/32061-h/32061-h.htm

Skinner, Anne Maria. Charles Lever and Ireland. University of Liverpool. PhD dissertation. May 2019.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

_______. "The Domestic Scene." The English Novel: A Panorama. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin and Riverside, 1960.

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

The Daltons

Next

Created 26 April 2022