The author has kindly shared with us this recent post from her blog, The Cabinet of Curiosity. It has been reformatted for our website, with different illustrations selected from an Internet Archive copy of the novel. Click on the images to enlarge them. — Jacqueline Banerjee

fter first meeting Jane, Rochester furthers their relationship by masquerading as a gypsy to discover her true impressions of him. His voice "wraps" her in "a kind of dream," "a web of mystification," until she instinctively believes an "unseen spirit had been sitting for weeks by [her] heart watching its workings and taking record of every pulse" (175). In a similar vein, Jane's cousin, St. John, acquires "a certain influence" over her that "took away [her] liberty of mind' (352) until she "fell under a freezing spell" (357), and felt his "influence in [her] marrow – his hold on [her] limbs" (359). In both these moments, Brontë portrays her male characters as having a mesmeric power over her female protagonist.

Mesmerism, (originally animal magnetism) was a therapeutic doctrine coined by Franz Mesmer in the eighteenth-century, but popularised by practitioners in the nineteenth. Mesmerists were thought to possess the power to place their subjects in a hypnotic state through the imposition of their own will on that of the subject. Mesmerism was often the practice of physicians, or gynaecologists, and was often used to "treat" hysteria. In this context, mesmerism becomes a potent but volatile force when combined with romance.

"Come, we will sit here in peace tonight." Source: Dent ed., facing p. 19.

Later in Jane Eyre, St. John's "despotic" effect on Jane is broken by Rochester's magnetic disembodied voice, which sets her spirit "trembling" in "exaltation" (373) and calls her to Thornfield. However, unlike St. John, who wishes for perfect submission from Jane, Rochester's language suggests that the power in their relationship mirrors a kind of erotic countertransference. Yet Rochester notes that Jane only "seems to submit"; for whilst he is compelled by "the sense of pliancy [she] impart[s]" he is "conquered" by her "influence" that "has a witchery beyond any triumph [he] can win." He figures Jane as a deceptively "soft, silken skein" that he can manipulate "around [his] finger" but "send[s] a thrill up [his] arm to [his] heart" (229).

Sigmund Freud in 1910 and Carl Jung in 1909, both of whom specialised in cases of female hysteria, warned against a patient's influence on the physician's unconscious feelings. They cite "cases of counter-transference when the analyst could not let go of the patient [and] both fall into the same dark hole of unconsciousness" (Jung 159, 157). This psychic void mirrors Jane's mounting fear, throughout the novel, of such a self-effacing abyss. It is this spiritual assimilation that Jane rallies against: "it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God's feet, equal — as we are!' (223). Significantly, during the nineteenth century the same mental vulnerability that was thought to predispose women to mesmeric susceptibility was also thought to make them attuned spiritual conduits. Psychiatry explicitly linked hysteria with female mediumship, pathologising it with terms like "psycholepsy" and "mediomania."

The spiritualist movement in many ways valorised the female mind and equipped women with a skill that afforded them a degree of financial independence. The fertile atmosphere of the séance not only provided spiritualists with the means to enter into the male domain of patriarchal discourse, but also allowed them to team up in order to trick countless men of scientific repute. Florence Cook, for example, a famous spiritualist, materialised during her séances as "Katie King," the spirit-world daughter of a seventeenth-century buccaneer.

In Jane Eyre it is frequently suggested that Jane's hysteria makes her susceptible to the spirit world; locked in the room of her uncle's death her nerves are "shaken" with "agitation" until she hears the "rushing of wings" and sees "a swift darting beam," "a herald of some coming vision from another world" (12). She often speaks involuntarily, accosting her aunt with the demands of a man long dead, "what would Uncle say to you, if he were alive?" whilst feeling "something spoke out of me over which I had no control" (21).

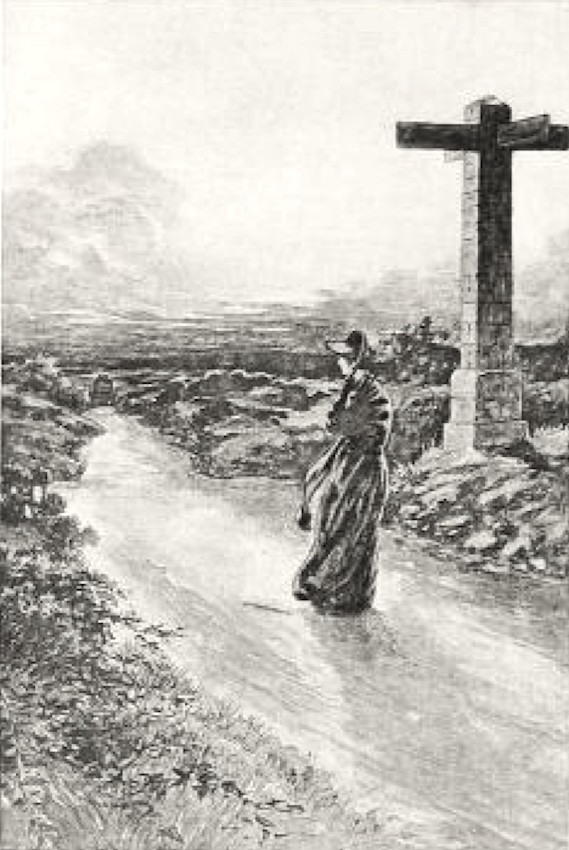

"I am alone." Source : Dent ed., frontispiece.

Jane herself is also presented as an inherently transient or ghostly figure: an orphan who has no place in the family home; a governess who must leave when the child matures; and a young woman who, before the novel's close, becomes only an evanescent bride. Mary Daly's theory of "female ghosthood" posits that denial of physical and mental space creates "invisible and subliminal ... space warps" that often make women feel alienated, "spacy or disorientated (18). These "space warps" slowly distend every time Jane is denied entry to the third floor of Thornfield, or told Bertha is "the creature of [her] over-stimulated brain" (250).

Jane's spiritualism intermittently manifests as incipient witchcraft; she is wary of her tenuous link to the supernatural, making "sure that nothing worse than [her]self haunted the shadowy room." Furthermore, Jane's metonymical epithets ("witch," "cat," "ignis fatuus," "sprite," "imp," "changeling," "elf" and "fairy") combined with Rochester's many assertions that Jane "has bewitched [his] horse" or "has the look of another world" (106) subtextually tie Jane's link to the supernatural with her hysteria.

Just as "female passivity [was considered] the leit-motif of powerful mediumship" [Dickerson 119), Jane's liminality empowers her; she is not fearful of Rochester's threat of violence but feels "an inward power; a sense of influence, which support[s] [her]" (267). Jane, like the female spiritualist movement, harnesses her supposed passivity – and transforms herself from a subject of masculine magnetism to a figure that possesses her own mesmerism.

Related Material

- Victorian Spiritualism

- "Last News from the Spirit-World" (Punch cartoon showing women participants in a séance)

- Victorian Spiritualism — Bibliography

References

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Ware, Herts: Wordsworth Classics, 1992.

[Illustrations] Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre (2 vol. ed, Vol II). Illustrated by H. S. Greig. London: Dent, 1896. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 25 April 2016.

Daly, Mary. Pure Lust: Elemental Feminist Philosophy. London: The Women's Press, 2001.

Dickerson, Vanessa D. Victorian Ghosts in the Noontide: Women Writers and the Supernatural. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1996.

Jung, C. G. Analytical Psychology: its Theory and Practice. Collected Works. Vol. 18. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976).

Created 25 April 2016