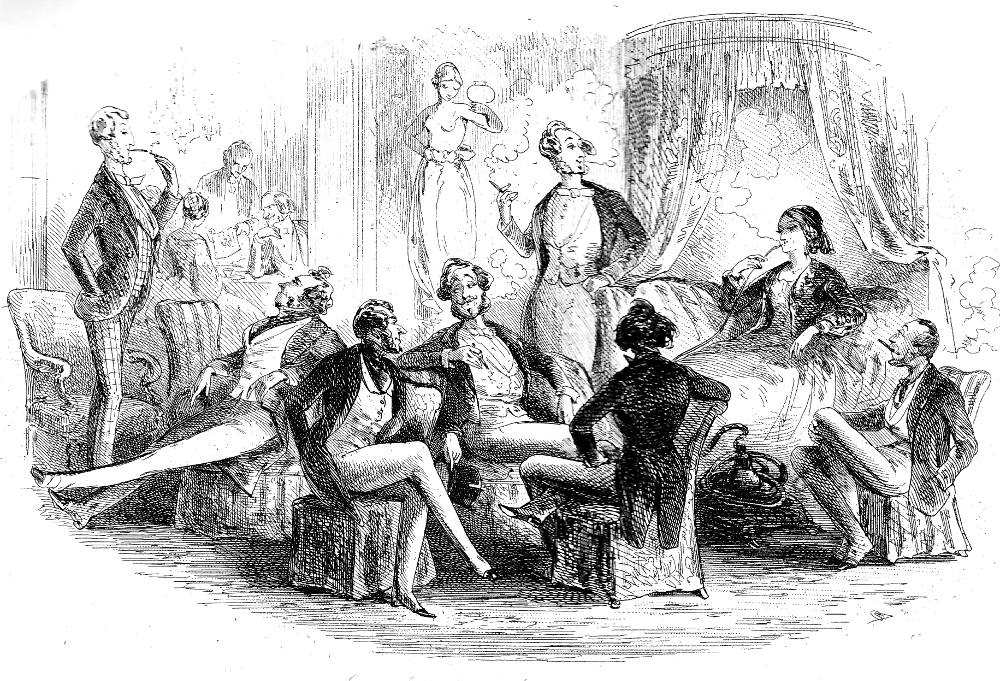

A Midnight reception — fifteenth illustration engraved by the Dalziels for the 1852 Chapman and Hall edition of The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). Chapter XXIV, "A Midnight Reception" (facing 182). 10 x 14.9 cm (3 ¾ by 6 ⅛ inches) vignetted. Note: This engraving serves as the title-page vignette for Volume One of the Little, Brown edition (Boston: 1904). It is only the second vertically-mounted plate in the Chapman & Hall 1852 and 1872 editions. For the title-page vignette for the initial Little, Brown volume, see The Journey. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: The Indolent Continental Aristocracy

In the adjoining room sat Kate Dalton at a tea-table. She was costumed for we cannot use any milder word in a species of “moyen-age” dress, whose length of stomacher and deep-hanging sleeves recalled the portraits of Titian's time; a small cap covered the back of her head, through an aperture in which the hair appeared, its rich auburn masses fastened by a short stiletto of gold, whose hilt and handle were studded with precious stones; a massive gold chain, with a heavy cross of the same metal, was the only ornament she wore. Widely different as was the dress from that humble guise in which the reader first knew her, the internal change was even greater still; no longer the bashful, blushing girl, beaming with all the delight of a happy nature, credulous, light-hearted, and buoyant, she was now composed in feature, calm, and gentle-mannered; the placid smile that moved her lips, the graceful motion of her head, her slightest gestures, her least words, all displaying a polished ease and elegance which made even her beauty and attraction secondary to the fascination of her manner. It is true the generous frankness of her beaming eyes was gone; she no longer met you with a look of full and fearless confidence: the cordial warmth, the fresh and buoyant sallies of her ready wit, had departed, and in their place was a timid reserve, a cautious, shrinking delicacy, blended with a quiet but watchful spirit of repartee, that flattered by the very degree of attention it betokened.

Perhaps our reader will not feel pleased with us for saying that was more beautiful now than before; that intercourse with the world, dress, manners, the tact of society, the stimulus of admiration, the assured sense of her own charms, however they may have detracted from the moral purity of her nature, had yet invested her appearance with higher and more striking fascinations. Her walk, her courtesy, the passing motion of her hand, her attitude as she sat, were perfect studies of grace. Not a trace was left of her former manner; all was ease, pliancy, and elegance. Two persons were seated near her: one of these, our old acquaintance, George Onslow; the other was a dark, sallow-visaged man, whose age might have been anything from thirty-five to sixty, for, while his features were marked by the hard lines of time, his figure had all the semblance of youth. By a broad blue ribbon round his neck he wore the decoration of Saint Nicholas, and the breast of his coat was covered with stars, crosses, and orders of half the courts of Europe. This was Prince Midchekoff, whose grandfather, having taken an active part in the assassination of the Emperor Paul, had never been reconciled to the Imperial family, and was permitted to reside in a kind of honorable banishment out of Russia; a punishment which he bore up under, it was said, with admirable fortitude. His fortune was reputed to be immense, and there was scarcely a capital of Europe in which he did not possess a residence. The character of his face was peculiar, for while the forehead and eyes were intellectual and candid, the lower jaw and mouth revealed his Calmuck origin, an expression of intense, unrelenting cruelty being the impression at once conveyed by the thin, straight, compressed lips, and the long, projecting chin, seeming even longer from the black-pointed beard he wore. There was nothing vulgar or common-place about him; he never could have passed unobserved anywhere, and yet he was equally far from the type of high birth. His manners were perfectly well bred; and although he spoke seldom, his quiet and attentive air and his easy smile showed he possessed the still rarer quality of listening well.

There was another figure, not exactly of this group, but at a little distance off, beside a table in a recess, on which a number of prints and drawings were scattered, and in the contemplation of which he affected to be absorbed; while, from time to time, his dark eyes flashed rapidly across to note all that went forward. He was a tall and singularly handsome man, in the dress of a priest. His hair, black and waving, covered a forehead high, massive, and well developed; his eyes were deep-set, and around the orbits ran lines that told of long and hard study, for the Abbe D'Esmonde was a distinguished scholar; and, as a means of withdrawing him for a season from the overtoil of reading, he had been attached temporarily as a species of Under-secretary to the Mission of the “Nonce.” In this guise he was admitted into all the society of the capital, where his polished address and gentle manner soon made him a general favorite. [Chapter XXIV, "A Midnight Reception," pp. 185-186]

Commentary: Lady Hester's Midnight Reception: A Real Smoker

European cigars now seem to be all the rage among the leisured classes in Phiz's depiction of Lady Hester Onslow's midnight reception of a group of almost entirely male ("the few privileged" turn out to be a roomful in Phiz) guests after the Opera. Her drawing-room and boudoir are hardly as "little" (184) as Lever depicts them in the Phiz illustration, although the apartment is an example of Rococco "gorgeous splendour" with its ottomans, sofas, and cigar smoke. Although Phiz has given Lady Hester "a small embroidered velvet cap" (184), he has given her something that Lever does mention, but which must have shocked readers in 1852: "a most splendidly ornamented hooka, the emerald mouthpiece of which she held in her hand" (1884). Since Lever mentions only "some half-dozen men" in evening dress, Phiz gives Lady Hester an audience of seven, although in the background (left) Kate Dalton appears is entertaining several more at a tea-table in an ante-room. The brilliance of the group composition is that, despite the varied poses, attitudes, and expressions of Lady Hester's upper-class guests, they are indeed "wearing away life in the dullest imaginable routine of dissipation" (185), hedonism which Phiz illustrates by the unrestrained smoking of the gathering.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Brown, John Buchanan. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1978.

Downey, Edmund. Charles Lever: His Life in Letters. 2 vols. London: William Blackwood, 1906.

Fitzpatrick, W. J. The Life of Charles Lever. London: Downey, 1901.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Lever, Charles. The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1852, rpt. 1872.

Lever, Charles James. The Daltons, or, Three Roads in Life. http://www.gutenberg.org//files/32061/32061-h/32061-h.htm

Skinner, Anne Maria. Charles Lever and Ireland. University of Liverpool. PhD dissertation. May 2019.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

_______. "The Domestic Scene." The English Novel: A Panorama. Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin and Riverside, 1960.

Last modified 26 April 2022