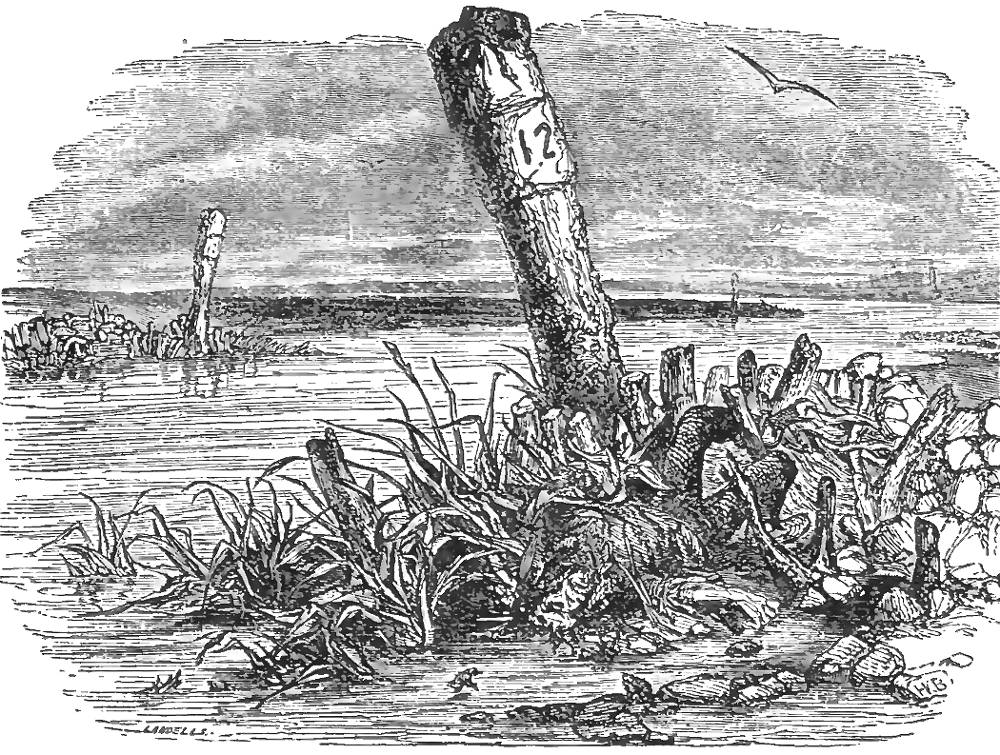

The Death of Quilp — Phiz's final illustration of Quilp's fortunes in Charles Dickens's Old Curiosity Shop. Wood engraving, 3 ⅛ x 4 ½ inches (8.4 x 11.5 cm). (16 January 1841). Vignette tailpiece to Chapter 67, the thirty-seventh instalment of the novel in Master Humphrey's Clock, Part 40. Vol. 2: 187. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Quilp's Sordid Remains

As the word passed his lips, he staggered and fell — and next moment was fighting with the cold dark water!

Another mortal struggle, and [Quilp] was up again, beating the water with his hands, and looking out, with wild and glaring eyes that showed him some black object he was drifting close upon. The hull of a ship! He could touch its smooth and slippery surface with his hand. One loud cry, now — but the resistless water bore him down before he could give it utterance, and, driving him under it, carried away a corpse.

It toyed and sported with its ghastly freight, now bruising it against the slimy piles, now hiding it in mud or long rank grass, now dragging it heavily over rough stones and gravel, now feigning to yield it to its own element, and in the same action luring it away, until, tired of the ugly plaything, it flung it on a swamp — a dismal place where pirates had swung in chains through many a wintry night — and left it there to bleach.

And there it lay alone. The sky was red with flame, and the water that bore it there had been tinged with the sullen light as it flowed along. The place the deserted carcass had left so recently, a living man, was now a blazing ruin. There was something of the glare upon its face. The hair, stirred by the damp breeze, played in a kind of mockery of death — such a mockery as the dead man himself would have delighted in when alive — about its head, and its dress fluttered idly in the night wind. [Chapter the Sixty-seventh, 187].

The Villain's Ignominious End

Quilp appears prominently in eighteen of the novel's seventy-three major wood-cuts in Master Humphrey's Clock, and in issue forty-two appears centrally as a disfigured (almost unrecognizable) corpse washed ashore in the reaches of the lower Thames in the Chapter 67 tailpiece (16 January 1841). The plate is not without phallic implications. Indeed, the pylon numbered "12" appears to rise from Quilp's crotch into a melancholy, brooding sky. Although he first appears in an illustration for issue 8, the hideous dwarf Daniel Quilp is one of the narrative-pictorial sequence's chief characters, across forty weekly issues (25 April 1840-6 February 1841):

In Phiz's image, the body of Quilp lies with his head diagonally slanted towards the bottom of the picture, his mouth a grimace, one hand a frozen claw. The picture reeks of mud, slime oozes underfoot, and huge piling thrusts priapically towards the sky. It is astonishing that Dickens, the author who wished never to publish anything that would make a young woman blush, did not veto this image, apparently totally oblivious of the enormous phallic symbol thrusting skywards. But those were the years before Freud. [Valerie Browne Lester, 82]

Phallic Symbolism in Quilp's Death

The modern reader, conversant with Freud and the concept of the subtext, cannot fail to note the phallic implications of the channel marker arising from the grasses and weeds on the shores of the Thames, the spot where Quilp's corpse (not easily distinguished) comes to rest. In her analysis of this daring illustration, Valerie Browne Lester notes the fundamental problem the plate poses: how could Dickens, consciously writing for a family readership, have permitted such a sexual illustration to accompany his thirty-ninth weekly episode? She draws our attention to the scene's phallic implications:

In Phiz's image, the body of Quilp lies with his head diagonally slanted towards the bottom of the picture, his mouth a grimace, one hand a frozen claw. The picture reeks of mud, slime oozes underfoot, and a huge piling thrusts priapically towards the sky. it is astonishing that Dickens, the author who wished never to publish anything that would make a young woman blush, did not veto this image, apparently totally oblivious of the enormous phallic symbol thrusting skywards. ["In the Work Saddle," 82]

At first, even the careful reader does not notice Quilp's corpse, and tends to construe the illustration as a piece of realistic scenery. However, she asserts that Phiz's emphasizing the weeds and the decaying wood constitutes an artistic comment on the nature of Quilp's existence, now so brutally terminated. At first, the reader does not notice the awkwardly posed corpse of Daniel Quilp, tangled in the weeds. The shattered pylons suggest that there was once a pier there, but little of it remains. Rottenness and rankness are a suitable setting for the foul corpse. No city lurks on the skyline, so that the villain dies far away from the city that nourished and supported him in his criminal enterprises. Disability, disuse, dysfunction, and decay are the apparent consequences of the industrial revolution, as epitomized by the ruined wharf and the derelict corpse. Far from being uncharacteristic of Phiz's humour, Frederic Kitton argues that the 1841 illustration is consistent with the illustrator's ability to make searching comments on the textual material he illustrated:

"Phiz" revelled in wild fun in the vignettes relating to the devilries of Mr. Daniel Quilp and the humours of Codlin and Short, and of Mrs. Jarley's waxwork show. His "Marchioness" was a distinct comic creation; but in the weird waterscape, showing the corpse of Quilp washed ashore, he sketched a vista of riparian scenery which, in its desolate breadth and loneliness, has not since, perhaps, been equalled, save in the amazing suggestive Thames etchings of Mr. James Whistler. [26]

Owing to Phiz's embedding the derelict corpse among the weeds, the picture even to Dickens may have suggested nothing more than a "riparian scene." Of the sixty-one illustrations that Phiz provided for the weekly serialisation, this is the one that eschews caricature to create a heightened realism.

Relevant illustrations from the Household Edition volumes (1872 and 1876)

Left: Furniss like Phiz presents the aftermath Quilp's drowning accident: The End of Quilp (1910). Right: Charles Green presents Quilp's death directly as he drowns in the Thames: The strong tide filled his throat, and bore him upon its rapid current. Green reacts to Phiz's overtly phallic symbolism by making the dying Quilp still clearly recognizable, but only as an enormous head about to inundated (1876).

Thomas Worth presents the almost prosaic details of Quilp's drowning: The relentless water bore him down. The illustration is a realistic reaction to Phiz's oblique treatment of the death of the villain (1872).

Related Resources

- The Old Curiosity Shop Illustrated: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Cattermole's Illustrations of The Old Curiosity Shop.

- Frontispieces to the three-volume edition of Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop, illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley in the James G. Gregory (New York) Household Edition (1861-71)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Boston Diamond Edition (1867)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Thomas Worth in the American Household Edition (1874)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Green in the British Household Edition (1876)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (13 lithographs from watercolours)

- Harold Copping (2 plates selected)

Scanned images and texts by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), George Cattermole, Daniel Maclise, and Samuel Williams. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Thomas Worth. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1872. VI.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. XII.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. V.

Kitton, Frederic George. "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne), a Memoir, Including a Selection From His Correspondence and Notes on His Principal Works. London, George Redway, 1882.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Last modified 12 November 2020