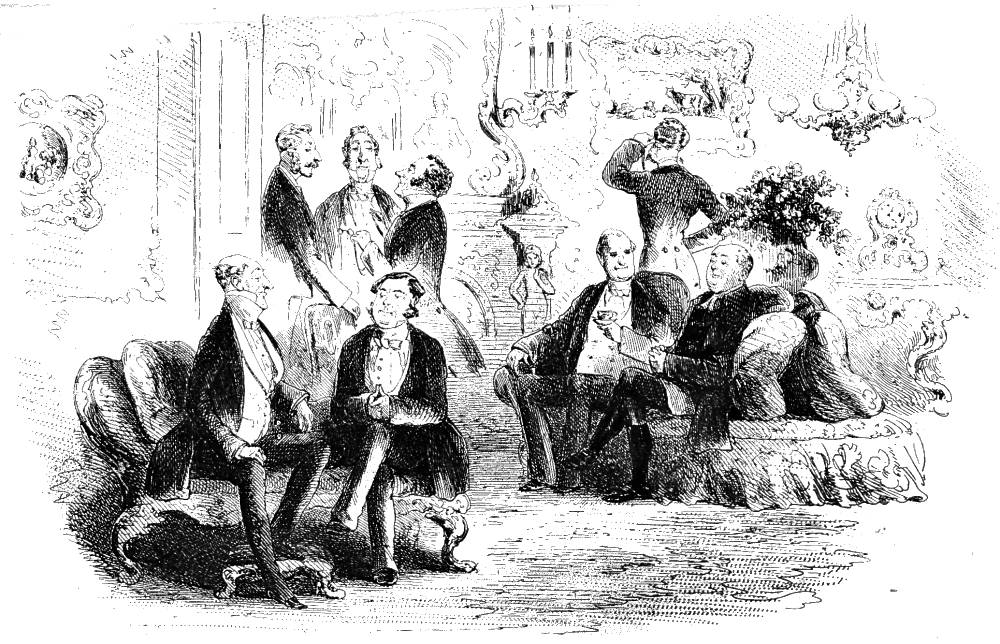

The Patriotic Conference by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) from Dickens's Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter12, "In which a Great Patriotic Conference is holden,"(Part 14: January, 1857), facing p. 488. 10.6cm by 16.3cm, vignetted. Source: Steig, Plate 112. [Return to text of Steig. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Mr.Merdle issued invitations for a Barnacle dinner. Lord Decimuswas to be there, Mr. Tite Barnacle was to be there, the pleasant young Barnacle was to be there; and the Chorus of Parliamentary Barnacles who went about the provinces when the House was up, warbling the praises of their Chief, were to be represented there. It was understood to be a great occasion. Mr. Merdle was going to take up the Barnacles. [478]

Bar was truly repentant, and would not say another syllable. Would Bishop favour him with half-a-dozen words? (He had now set Mr.Merdle down on a couch, side by side with Lord Decimus, and to it they must go, now or never.)

And now the rest of the company, highly excited and interested, always excepting Bishop, who had not the slightest idea that anything was going on, formed in one group round the fire in the next drawing-room, and pretended to be chatting easily on the infinite variety of small topics, while everybody's thoughts and eyes were secretly straying towards the secluded pair. The Chorus were excessively nervous, perhaps as labouring under the dreadful apprehension that some good thing was going to be diverted from them! Bishop alone talked steadily and evenly. He conversed with the great Physician on that relaxation of the throat with which young curates were too frequently afflicted, and on the means of lessening the great prevalence of that disorder in the church. Physician, as a general rule, was of opinion that the best way to avoid it was to know how to read, before you made a profession of reading. Bishop said dubiously, did he really think so? And Physician said, decidedly, yes he did. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 12, "In which a Great Patriotic Conference is holden," p. 488.

Commentary

Accordingly, the novelist's treatment of the "patriotic" conference for bringing Merdle and Lord Decimus Barnacle together to [168/169] arrange a rich bit of patronage is very much in the traditions of political caricature, if not literary allegory. Bar, Bishop, Physician, and Chorus are representative types rather than individuals, and this is consistent with all of the Barnacle imagery. Yet, except for the Bishop's collar, there is no way of distinguishing the types in Browne's illustration, The Patriotic Conference (Bk. 2, ch. 12). If we read ahead to page 427, we find that the three men shown behind Merdle and Lord Decimus are the "Chorus," while Bishop's companion is Physician, but in earlier Dickens novels one would not have to consult the text this closely in order to understand an illustration (whereas in "Sixties" illustrations the picture usually relies heavily on the text). Phiz's men are realized as individuals, not as types. One of his problems here is that Dickens has virtually dispensed with physical description beyond Merdle's habit of taking himself into custody. Yet were Phiz to label the characters with obvious symbols of their professions, the result would seem primitive, and jar with the rest of his work in this novel.

In this instance, it is difficult to dispute the argument that Dickens no longer needs an illustrator: illustrations do not work for this particular episode because Dickens chose to make use of a highly stylized, nonrealistic technique. His private imagination is still visual, however, as can be inferred from his instruction to Browne, "Don't have Lord Decimus's hand put out, because that looks condescending; and I want him to be upright, stiff, unmixable with more mortality" (N, 2: 814.) — an instruction Browne followed as best he could. And similarly, in Mr. Merdle becomes a Borrower (Bk. 2. ch. 24), the financier is remarkable for little but his awkward, bearish, shambling appearance and the blankness of his face, consistent with our sense of him as a nonentity; yet Browne, now eschewing caricature, could not match the effectiveness of the text, nor could he add anything to it through traditional iconography. — Steig, 168-169.

The only figure whose clothing suggests his profession, as Steig notes, is the Church of England Bishop, right. Above him, one of the dinner guests, presumably a connoisseur of art, with his eyeglass studies the details in a seventeenth-century Dutch painting of cattle such as those by Cuyp and Paulus Potter: "his Lordship composed himself into the picture after Cuyp, and made a third cow in the group" (482) gave Phiz a hint as to how the powerbrokers might be arranged, and then Phiz actually incorporated such a painting into the background. However, the man at the painting is not Lord Decimus, for Merdle and Lord Decimus are the well-dressed, middle-aged businessmen in the left foreground — and in this cameo Merdle even resembles somewhat his ceal-life original, financier and Member of Parliament John Sadleir.

This is does not appear to be the same drawing-room ("the ladies' withdrawing-room") which forms the backdrop of Society expresses its Views on a Question of Marriage. The reception room, state-room, or grand salon is brilliantly lit and sumptuously furnished — and the middle-aged men who have just adjourned here from the dining-room are entirely undistinguished, unremarkable, and interchangeable, but, as Steig notes, they are at least individualised. Probably because he is so non-descript and a mere appendage of Mrs. Merdle, the other illustrators do not depict him.

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Phiz. The Authentic Edition. London:Chapman and Hall, 1901. (rpt. of the 1868 edition).

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 14 May 2016