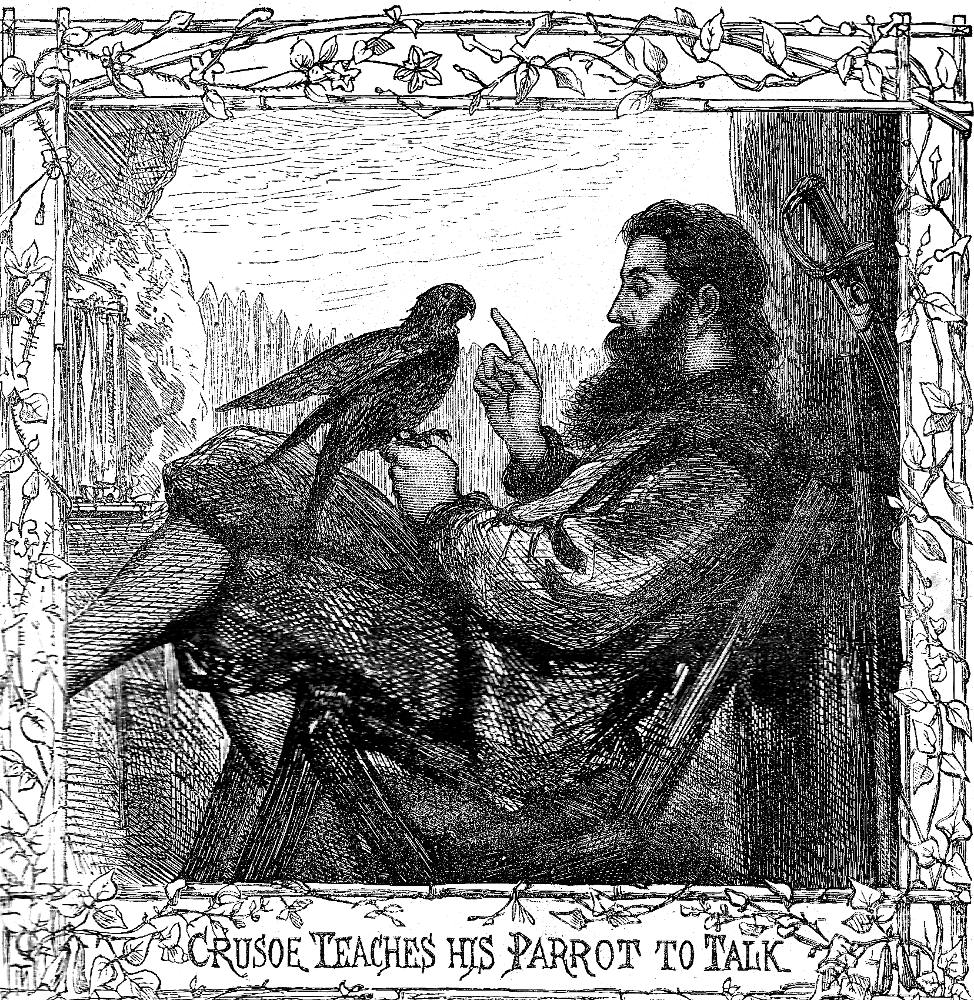

How like a king I dined (p. 106) contrasts the active Crusoe who by daylight has explored the island and exploited its resources with the domestic Crusoe, enjoying his surrogate family. Middle of page 109, vignetted: approximately 8.4 cm high by 10.5 cm wide, signed "Wal Paget" in the lower right-hand quadrant. Running head: "My Country Seat" (p. 109).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

It would have made a Stoic smile to have seen me and my little family sit down to dinner. There was my majesty the prince and lord of the whole island; I had the lives of all my subjects at my absolute command; I could hang, draw, give liberty, and take it away, and no rebels among all my subjects. Then, to see how like a king I dined, too, all alone, attended by my servants! Poll, as if he had been my favourite, was the only person permitted to talk to me. My dog, who was now grown old and crazy, and had found no species to multiply his kind upon, sat always at my right hand; and two cats, one on one side of the table and one on the other, expecting now and then a bit from my hand, as a mark of especial favour. [Chapter XI, "Finds Print of a Man's Foot in the Sand," page 106]

Commentary: Variation on a Standard Visual Theme

With a fairly thorough knowledge of a number of nineteenth-century programs of illustration from Thomas Stothard to George Cruikshank and Phiz, Paget is responding as much to earlier interpretations of this scene as the text itself. His particular contribution to the various realisations of Crusoe's "animal court" is the high degree of realism, approaching photographic fidelity, Paget achieves using the new medium of the lithograph. In particular, Paget reproduces every hair of the dog, of the cats, and of Crusoe's "island dress" with startling clarity. Thematically, the hairiness of these four figures implies a connection, or an equality, as all four mammals present enjoy not merely a meal but each other's presence. Significantly, Paget has included Poll the Parrot from this golden circle, for he sits as Crusoe's chief confidant upon his shoulder. Even a "Stoic," remarks the narrator (i. e., a philosopher who rigorously disciplines the emotions in order to achieve spiritual detachment from the body and ephemeral bodily pleasures) would have enjoyed the vision of Crusoe's domestic felicity. Paget admirably places the reader in the position of that hypothetical philosopher, but fails to communicate visually Defoe's playful tone. If Paget has lost something of the amiability of the 1831 Cruikshank illustration, he has nonetheless captured the harmonious nature of Crusoe's relationship with his domesticated animals that implies Crusoe's enjoying a species of the Golden Age on the otherwise uninhabited tropical island that in so many ways Paget interprets as offering the Noble Savage an Edenic existence.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

King Crusoe and his Animal Court, 1790-1863-64

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the interior of the hut inthe rainy season, Robinson Crusoe at work in his cave.Centre: A realisation of the interior of the hut,Robinson Crusoe reading the Bible (1818), his "court" here being a congregation. Right: TheCassell's study of Crusoe's instructing Poll the Parrot, Crusoeteaching his Parrot to talk (1863-64). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: George Cruikshank's amiablewood-engraving of Crusoe's holding court with his animal courtiers, Crusoe and Poll the Parrot in dialogue (1831).

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Last modified 29 April 2018