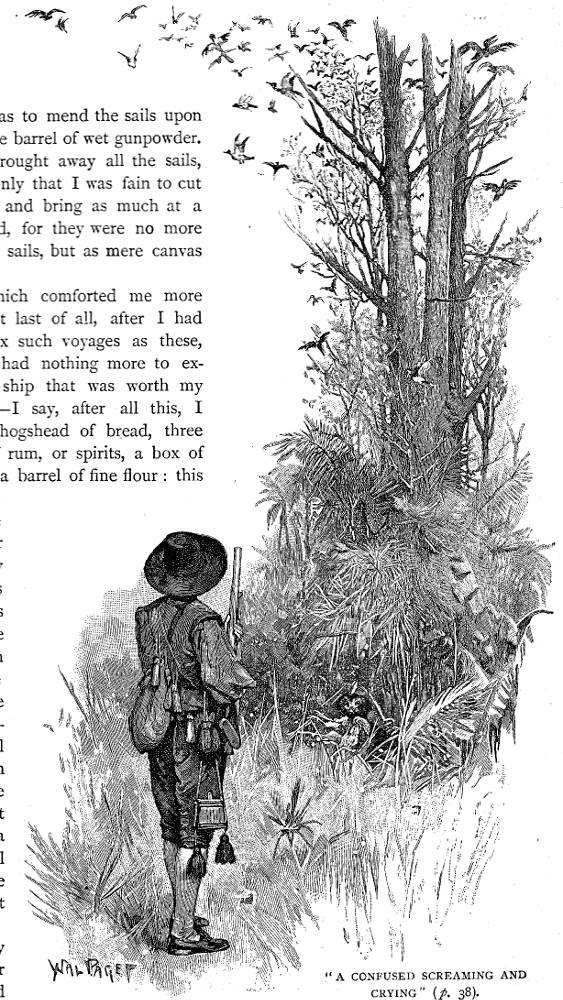

A confused screaming and crying

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

half-page lithograph

14 cm high by 12 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, embedded on page 40.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: "the island I was in was barren"

I found also that the island I was in was barren, and, as I saw good reason to believe, uninhabited except by wild beasts, of whom, however, I saw none. Yet I saw abundance of fowls, but knew not their kinds; neither when I killed them could I tell what was fit for food, and what not. At my coming back, I shot at a great bird which I saw sitting upon a tree on the side of a great wood. I believe it was the first gun that had been fired there since the creation of the world. I had no sooner fired, than from all parts of the wood there arose an innumerable number of fowls, of many sorts, making a confused screaming and crying, and every one according to his usual note, but not one of them of any kind that I knew. As for the creature I killed, I took it to be a kind of hawk, its colour and beak resembling it, but it had no talons or claws more than common. Its flesh was carrion, and fit for nothing. [Chapter IV, "First Weeks on the Island," page 38]

Commentary: Crusoe interacts with the Nature of the Island

Heretofore, Crusoe has been reacting with other people, in camaraderie and conflict. Now, Paget depicts him by himself in long series of illustrations interacting with the natural environment: sleeping in a tree within sight of the ocean, hunting birds and goats, interacting with the ship's dog, discovering barley growing on the island, sharpening tools salvaged from the wreck, catching turtles and dolphins, and broiling meat over hot coals.He has become the embodiment of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Noble Savage, but without any society but that of animals. Paget delights in these scenes, representing the multiple species and tropical foliage of theCaribbeanisland.And Paget sees the mature protagonist as a keen observer and problem-solver whose biggest struggle is not with the elements, but with the loneliness of living in a previously uninhabited tropical paradise.A properly clothed European huntsman, Crusoe confronts the dense forest as he attempts to bring down birds; their presence (and later, that of the goats) negates Crusoe's assessment of the island as "barren" (38), that is, devoid of European crop species and domesticated animals such as cattle; and, in fact, his assessment of it as "uninhabited" we eventually call into question as it becomes evident that the island is part of the traditional territories and ancestral lands of the Carribb peoples living on the nearby mainland as they use it for their ceremonies.

The illustration imposes itself on the text, asserting its hegemony by compelling the column of print to shrink in width to accommodate the image of the hunter and of the birds above. This relationship is not entirely new as Dickens's illustrators, for example, had employed it in dropping wood-engravings in the texts of the Christmas Books that followed the more conventionally laid out A Christmas Carol of 1843. Indeed, Paget here compels readers to assimilate the image into their understanding of the passage two pages earlier, even as it is juxtaposed against the following, later passage with which it sharles page40:

small ropes and rope-twine I could get, with a piece of spare canvas, which was to mend the sails upon occasion, and the barrel of wet gunpowder. In a word, I brought away all the sails, first and last; only that I was fain to cut them in pieces, and bring as much at a time as I could, for they were no more useful to be sails, but as mere canvas only.

But that which comforted me more still, was, that last of all, after I had made five or six such voyages as these, and thought I had nothing more to expect from the ship that was worth my meddling with—I say, after all this, I found a great hogshead of bread, three large runlets of rum, or spirits, a box of sugar, and a barrel of fine flour; this was surprising to me, because I had given over expecting any more provisions, except what was spoiled by the water. I soon emptied the hogshead of the bread, and wrapped it up, parcel by parcel, in pieces of the sails, which I cut out; and, in a word, I got all this safe on shore also.

The next day I made another voyage, and [Chapter IV, "First Weeks on the Island," page 40]

Paget focuses on Crusoe's exploring the island's natural resources and not, as previous illustrators have done, on his rafting supplies off the derelict ship. In other words, in the Paget illustrations Crusoe makes a clean break with the wreck, representative of European civilisation, and becomes an "islander" who will survive as a hunter-gatherer rather than a salvager.

Related Material

- The Reality of Shipwreck

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 25 April 2018