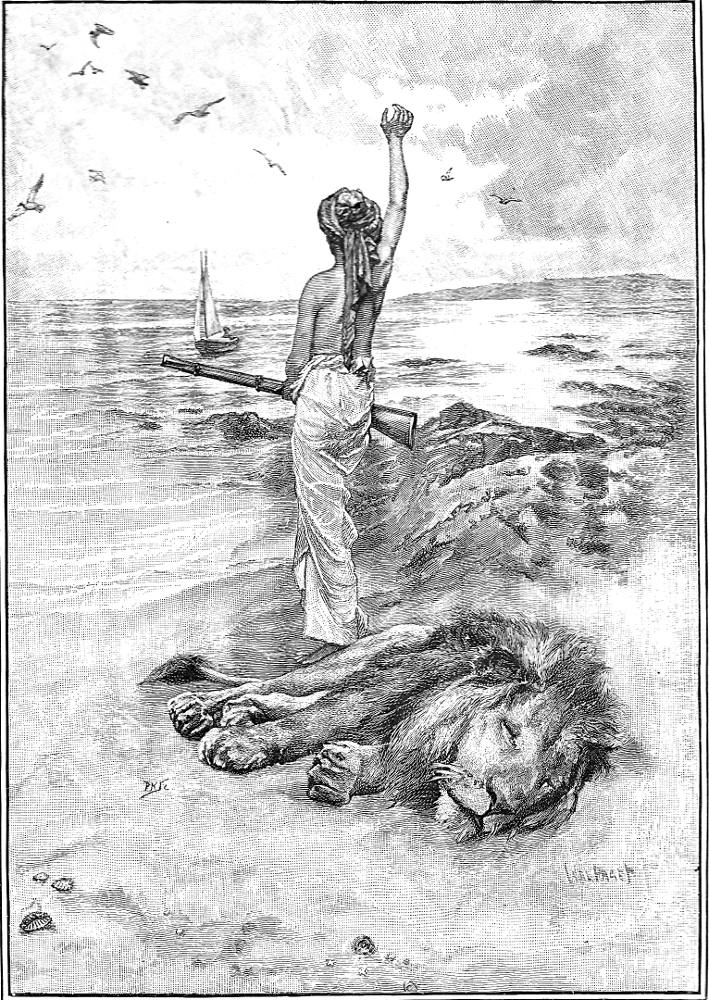

This was game indeed

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

lithographic frontispiece

18.1 cm high by 12.9 cm wide, framed.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, facing title-page.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Related material

Passage Anticipated by the Frontispiece

“Xury,” says I, “you shall on shore and kill him.” Xury, looked frighted, and said, “Me kill! he eat me at one mouth!”—one mouthful he meant. However, I said no more to the boy, but bade him lie still, and I took our biggest gun, which was almost musket-bore, and loaded it with a good charge of powder, and with two slugs, and laid it down; then I loaded another gun with two bullets; and the third (for we had three pieces) I loaded with five smaller bullets. I took the best aim I could with the first piece to have shot him in the head, but he lay so with his leg raised a little above his nose, that the slugs hit his leg about the knee and broke the bone. He started up, growling at first, but finding his leg broken, fell down again; and then got upon three legs, and gave the most hideous roar that ever I heard. I was a little surprised that I had not hit him on the head; however, I took up the second piece immediately, and though he began to move off, fired again, and shot him in the head, and had the pleasure to see him drop and make but little noise, but lie struggling for life. Then Xury took heart, and would have me let him go on shore. “Well, go,” said I: so the boy jumped into the water and taking a little gun in one hand, swam to shore with the other hand, and coming close to the creature, put the muzzle of the piece to his ear, and shot him in the head again, which despatched him quite.

This was game indeed to us, but this was no food; and I was very sorry to lose three charges of powder and shot upon a creature that was good for nothing to us. However, Xury said he would have some of him; so he comes on board, and asked me to give him the hatchet. “For what, Xury?” said I. “Me cut off his head,” said he. However, Xury could not cut off his head, but he cut off a foot, and brought it with him, and it was a monstrous great one. [Chapter II, "Slavery and Escape," p.20]

Commentary

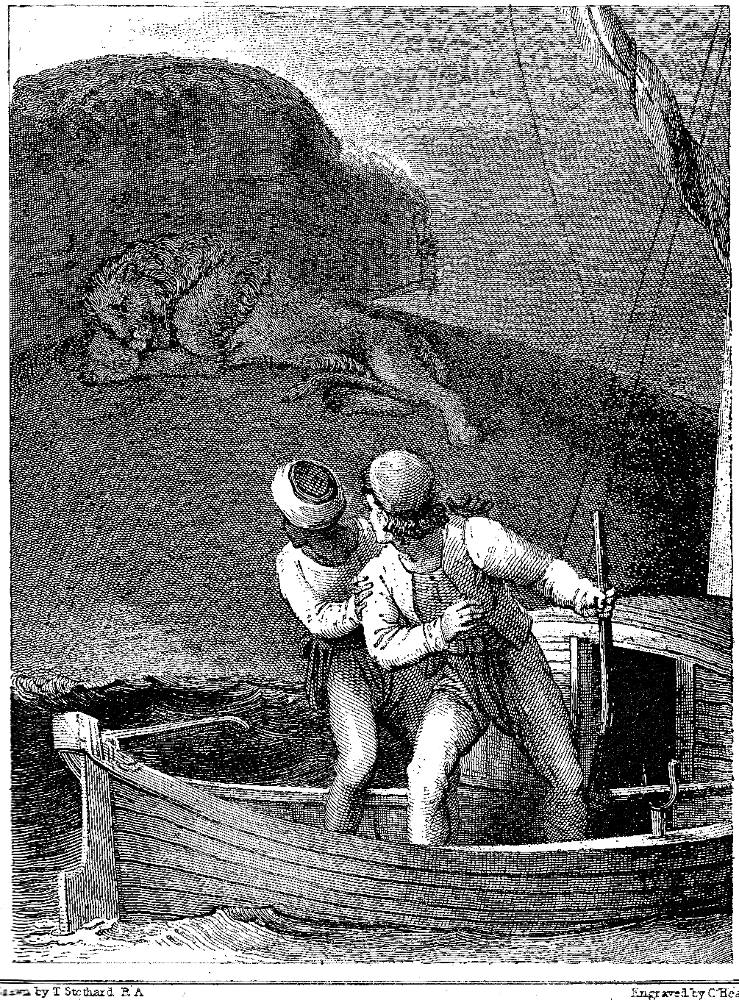

Although Crusoe's adventures inspired a number of nineteenth-century illustrators, only Thomas Stothard has dealt the incident involving the boy Xury's having to overcome terror of the lions onshore, stylishly realised in Robinson Crusoe and Xury alarmed at the sight of a lion in John Stockdale's 1790 edition. Although Stothard is not working in a realistic idiom, he effectively conveys the paralysing anxiety of the escaped slaves. However, Paget has advanced the credibility of the episode by portraying an anatomically correct African lion, and establishing the perspective from the shore. Paget, moreover, reconceptualizes the moment as one of personal triumph as Xury raises his hand to Crusoe on board the boat in the distance, emphasizing the contrast between the willowy boy and the massive beast that he has just shot.

Paget had the advantage over all previous illustrators because he had had the opportunity to study the narrative-pictorial series of Thomas Stothard, George Cruikshank, Hablot Knight Browne, and probably Sir John Gilbert and Edward Henry Wehnert. Accordingly, Paget rejected the notion of beginning with dancing cannibals, or Crusoe on the island, or Crusoe arguing with his father. He must have felt that the lion-hunting scene would serve as a keynote for the themes and conflicts of the novel, with a foreign shore, an exotically dressed boy, and a small vessel, elements that occur later in the narrative. The scale of the frontispiece, however, is anything but typical of Paget's work here as only thirteen such full-page lithographs in the 1891. These are, moreover, the only illustrations in which Paget provides much context for the action, the remaining 107 being mere vignettes that have only rudimentary backdrops. His subtitle, (See p. 20.) enables the reader to jump right to the passage realised.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), a Children's Book (1815), Cruikshank (1831), Wehnert (1862), and Cassell's (1863-64)

Left: Stylish late 18th c. realisation of the same episode, Robinson Crusoe and Xury alarmed at the sight of a lion (1790). Centre: A Chapbook-like woodblock engraving with broken chains, signifying young Crusoe's escaping slavery, Robinson Crusoe throwing the Moor overboard (1815). Right: Wehnert's realisation of the same scene, with a highly realistic and dynamic interpretation: Crusoe throwing the Moor overboard (1862). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: George Cruikshank's highly realistic wood-engraving of Crusoe's initiating his escape from slavery off the coast of Sallee, Crusoe tosses the Moorish deckhand overboard (1831). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Above: Cassell's highly realistic wood-engraving of the Corsair fishing-boat and the coast of Sallee, Crusoe escapes with Xury (1863-64). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 24 March 2018