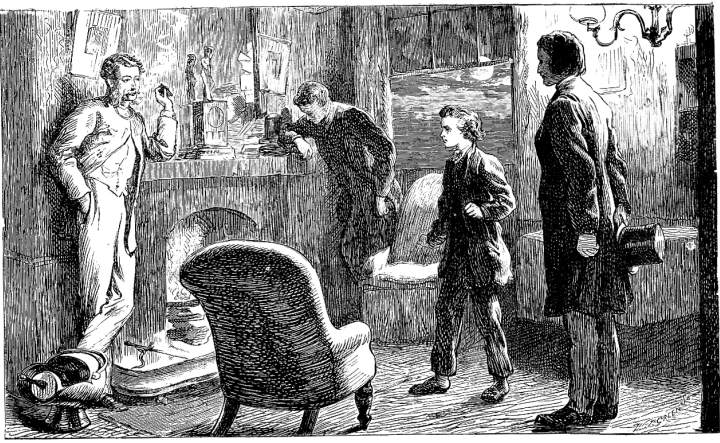

Forming The Domestic Virtues by Marcus Stone. Wood engraving by Dalziel. 9.5 cm high x 15.9 cm wide. Second illustration for the seventh monthly number of Our Mutual Friend, Chapter Six, "A Riddle without an Answer," in the second book, "Birds of a Feather." The Authentic edition, facing p. 246. [This part of the novel originally appeared in periodical form in November 1864.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

Working Class and Upper-Middle Class Worlds Collide: Charlie Hexam and Bradley Headstone visit Mortimer Lightwood and Eugene Wrayburn in their chambers

In the November 1864 monthly number, Marcus Stone realizes the moment at which Charlie Hexam and his mentor, the schoolmaster Bradley Headstone, confront Eugene Wrayburn about his interest in Lizzie, a confrontation loaded with class-consciousness and antipathy as the working-class brother suspects that the indolent, upper-middle-class attorney means to exploit his sister sexually. The scene, set in the Temple, in the rooms (as opposed to the offices) of the attorneys Eugene Wrayburn and Mortimer Lightwood, confirms the latter's suspicions that something is deeply troubling his friend. In fact, Bradley Headstone and his star pupil, Charlie Hexam, have dared to venture outside their working-class milieu to demand that Eugene severe his relationship with Lizzie.

For those unacquainted with Victorian London, the Inns of Court — the Middle Temple, the Staple Inn and the Inner Temple — occupy the area between Fleet Street and the Thames; and here Pip and his friend Herbert Pocket had rooms in Garden Court in Great Expectations (1861). The area takes its name from the Order of the Knights Templar, who owned these properties in the Middle Ages. Nearby is Temple Bar, which separates the City of London from the City of Westminster.

Moment realised in this illustration:

Both the wanderers looked up towards the window; but, after interchanging a mutter or two, soon applied themselves to the door-posts below. There they seemed to discover what they wanted, for they disappeared. from view by entering at the doorway. 'When they emerge,' said Eugene, 'you shall see me bring them both down;' and so prepared two pellets for the purpose.

He had not reckoned on their seeking his name, or Lightwood's. But either the one or the other would seem to be in question, for there came a knock at the door. 'I am on duty to-night,' said Mortimer, 'stay you where you are, Eugene.' Requiring no persuasion, he stayed there, smoking quietly, and not at all curious to know who knocked, until Mortimer spoke to him from within the room, and touched him. Then, drawing in his head, he he found the visitors to be young Charley Hexam and the schoolmaster; both standing facing him, and both recognised at a glance.

'You recollect this young fellow, Eugene?' said Mortimer.

'Let me look at him,' returned Wrayburn, coolly. 'Oh, yes, yes. I recollect him!'

He had not been about to repeat that former action of taking him by the chin, but the boy had suspected him of it, and had thrown up his arm with an angry start. Laughingly, Wrayburn looked to Lightwood for an explanation of this odd visit.

'He says he has something to say.'

'Surely it must be to you, Mortimer.'

'So I thought, but he says no. He says it is to you.'

'Yes, I do say so,' interposed the boy. 'And I mean to say what I want to say, too, Mr. Eugene Wrayburn!'

Passing him with his eyes as if there were nothing where he stood, Eugene looked onto Bradley Headstone. With consummate indolence, he turned to Mortimer, inquiring: 'And who may this other person be?'

'I am Charles Hexam's friend,' said Bradley, 'I am Charles Hexam's schoolmaster.'

'My good sir, you should teach your pupils better manners,' returned Eugene.

Composedly smoking, he leaned an elbow on the chimney-piece, at the side of the fire, and looked at in the schoolmaster. It was a cruel look, in its cool disdain of him, as a creature of no worth. The schoolmaster looked at him, and that, was a cruel look, though of the different kind, that it had a raging jealousy and fiery wrath in it.

Very remarkably, neither Eugene Wrayburn nor Bradley Headstone looked at all at the boy. Through the ensuing dialogue, those two, no matter who spoke, or whom was addressed, looked at each other. There was some secret, sure perception between them, which set them against one another in all ways. [249]

The composition complements, too, the running heads of the page between the reader's encountering the illustration, facing p. 246 — "Mortimer's Suspicions" (247) — and that of the page realised, "Visitors to Mr. Eugene Wrayburn" (249), which explain Mortimer Lightwood's anguished pose and the context of the illustration the reader has just seen. Like the best illustrations of such earlier visual commentators as John Leech, George Cruikshank, and Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) this woodcut by Marcus Stone prepares the reader for a significant event in the narrative and compels the reader to be more attentive to nuances of the text that shed light on the characters' motivations, attitudes, and relationships. The illustration itself reflects the juxtapositions of the figures which Dickens describes in the pages immediately following the picture, which is therefore a reflection of the text, just as Eugene is a reflection of Mortimer and Charlie is a reflection of Bradley; the central visual metaphor of the woodcut, therefore, is the mirror above the mantelpiece in which the figurine atop the clock is reflected and into whose frame correspondence and cards have been jammed. With little to go on other than Dickens's descriptions of the figures themselves and their utterances, Stone has provided the standard furnishings for the upper-middle class bachelors' rooms:a coal burning fire-place with a clock on the mantle and a brass fender, coal scuttle, and poker (lower left); a brace of easy-chairs, a nondescript carpet, a table, a gassolier (upper right); and to either side of the fire-place a pair of pictures that complement the dualities in the scene: two sets of characters from two entirely different classes pursuing different agendas. The placement and title of these pictures — which in a Phiz illustration would have definite subjects reflecting the nature of the conflict, but which in Stone are merely a vehicle for drawing the viewer's attention away from the central figure, Charlie, towards the two lawyers — complements the contrasting postures of Lightwood and Wrayburn, whose extremely casual stance and smoking as he leans an elbow on the mantle the text describes most particularly, so that both media focus the reader's attention on Eugene ("Well-born") Wrayburn.

Behind Charlie's head are such naturalistic details as a full moon, clouds, and a darkened skyline, indicating the time of day and the proximity of these rooms to the great river which connects the lives of so many of the characters in the novel. The Schoolmaster and his protege come from that larger, grittier world but dimly apprehended from the window of the comfortable upper-middle class bachelors' room. The frock coats of all four males reveal their professional status (at least in the case of the attorneys) or their aspirations to professional status (in the case of the teacher and his monitor). The proper, middle-class top-hat and dark wool coat convey Bradley Headstone's sense of himself as a member of an emerging profession in the decade preceding the General Education Act.

The focus of the figures' attentions is, however, the indolent figure of Eugene Wrayburn, whom Charlie will shortly warn off his sister. In the scene, the Schoolmaster seems a rigid pillar, firm, physically commanding, and self-controlled; his shadowed face, seen only in profile, communicates no emotion. The picture therefore betrays no sense of Headstone's growing anxiety at being taunted by a social superior; we do not notice "pale and quivering lips" (250) which prepare us for Bradley's being driven "well-nigh mad" (251) by the supercilious Eugene's goading.

Eugene, as in the subsequent passage, regards the Schoolmaster with a "disinterested" air and ignores Charlie completely. Stone depicts Eugene standing to the other side of the fire-place, his friend Mortimer on the other side, by the window, and the boy caught in the middle. Eugene does indeed have a hair-guard for his watch, but Stone has again extended the text by supplying the waistcoat and fashionable trousers. Between his sister's admirer and his mentor stands Charlie, serious and (as the position of his raised left hand suggests) determined to be heard by those taller and more powerful than himself.

An interesting aspect of Stone's composition is the fourth figure's posture: Mortimer Lightwood has literally receded into the background, keeping his head down, not regarding any of the other characters, but listening attentively (as in the text, he is nearest the window, but is not looking out). In contrast to this anguished pose is Eugene'; he exudes "attitude" as he enjoys his cigar and tormenting Headstone with "perfect placidity" (250) designed to infuriate and belittle his interlocutors. The picture thus sets up expectations in the reader as to what he or she will momentarily encounter in the print medium; at the moment of realisation, the reader undoubtedly went back in the text, seeking to decode the characters' postures and expressions.

References

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

"Gray's Inn: Origins." The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn. Accessed 15 February 2011.

"Inns of Court." Wikipedia. Accessed 15 February 2011.

"Middle Temple." Wikipedia. Accessed 15 February 2011.

"Temple Bar." Wikipedia. Accessed 15 February 2011.

Last modified 15 February 2011