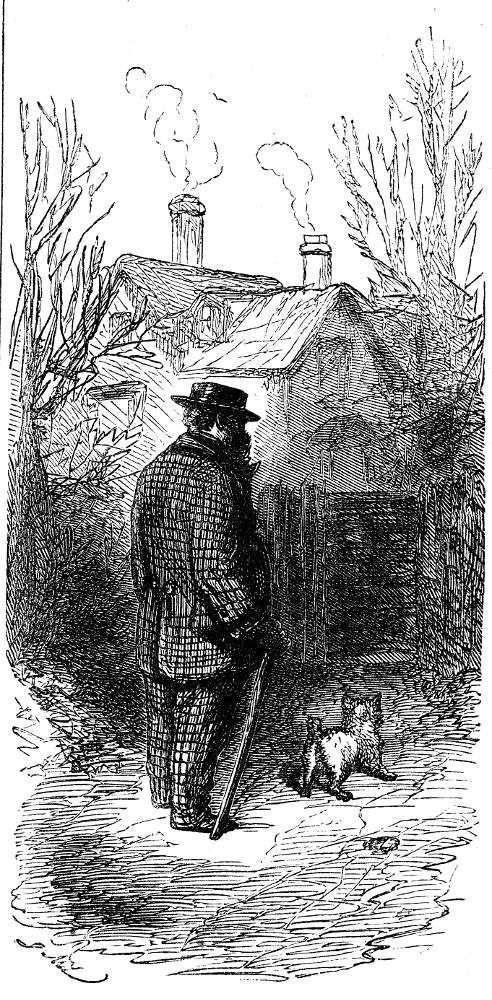

Coping with the prospect of Frank's leaving Combe-Raven, Magdalen confesses her love for the young man with few prospects to her father in the garden: “He might marry me.” — the accompanying headnote vignette for "The First Scene," Chapter IX, involves Magdalen and her father paying Mr. Clare a morning visit at his cottage on the Combe-Raven estate in Wilkie Collins's No Name, first published in All the Year Round and Harper's Weekly (Vol. VI-No. 274), Number 5 (the 12 April 1862 instalment); vignette: 11.6 cm high by 5.7 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted; with the smaller and regular illustrations both appearing on p. 237 in the serial). The main plate, also a wood-engraving, appears at the bottom of the folio page in the serial: 11.7 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed; top of p. 39 in volume's Chapter IX. These two illustrations are positioned on different pages in the volume: p. 41 for the vignette within Chapter IX.

Curtain Passage Realised in the Main Plate: The Surprised Father Consoles Magdalen

“Don’t you think it’s hard to be sent away for five years, to make your fortune among hateful savages, and lose sight of your friends at home for all that long time? Don’t you think Frank will miss us sadly? Don’t you, papa? — don’t you?”

“Gently, Magdalen! I’m a little too old for those long arms of yours to throttle me in fun. — You’re right, my love. Nothing in this world without a drawback. Frank will miss his friends in England: there’s no denying that.”

“You always liked Frank. And Frank always liked you.”

“Yes, yes — a good fellow; a quiet, good fellow. Frank and I have always got on smoothly together.”

“You have got on like father and son, haven’t you?”

“Certainly, my dear.”

“Perhaps you will think it harder on him when he has gone than you think it now?”

“Likely enough, Magdalen; I don’t say no.”

“Perhaps you will wish he had stopped in England? Why shouldn’t he stop in England, and do as well as if he went to China?”

“My dear! he has no prospects in England. I wish he had, for his own sake. I wish the lad well, with all my heart.”

“May I wish him well too, papa — with all my heart?”

“Certainly, my love — your old playfellow — why not? What’s the matter? God bless my soul, what is the girl crying about? One would think Frank was transported for life. You goose! You know, as well as I do, he is going to China to make his fortune.”

“He doesn’t want to make his fortune — he might do much better.”

“The deuce he might! How, I should like to know?”

“I’m afraid to tell you. I’m afraid you’ll laugh at me. Will you promise not to laugh at me?”

“Anything to please you, my dear. Yes: I promise. Now, then, out with it! How might Frank do better?”

“He might marry Me.”

If the summer scene which then spread before Mr. Vanstone’s eyes had suddenly changed to a dreary winter view — if the trees had lost all their leaves, and the green fields had turned white with snow in an instant — his face could hardly have expressed greater amazement than it displayed when his daughter’s faltering voice spoke those four last words. He tried to look at her — but she steadily refused him the opportunity: she kept her face hidden over his shoulder. Was she in earnest? His cheek, still wet with her tears, answered for her. There was a long pause of silence; she waited — with unaccustomed patience, she waited for him to speak. He roused himself, and spoke these words only: “You surprise me, Magdalen; you surprise me more than I can say.” [Chapter IX: 239 in serial, pp. 38-39 in volume]

Passage Realised in the Vignette: Mr. Vanstone and His Terrier Approach Clare's Cottage

Magdalen went out with her father.

“Papa!” she whispered anxiously, as they descended the stairs; “you don’t think Mr. Clare will say No?”

“I can’t tell beforehand,” answered Mr. Vanstone. “I hope he will say Yes.”

“There is no reason why he should say anything else — is there?”

She put the question faintly, while he was getting his hat and stick; and he did not appear to hear her. Doubting whether she should repeat it or not, she accompanied him as far as the garden, on his way to Mr. Clare’s cottage. He stopped her on the lawn, and sent her back to the house.

“You have nothing on your head, my dear,” he said. “If you want to be in the garden, don’t forget how hot the sun is — don’t come out without your hat.”

He walked on toward the cottage.

She waited a moment, and looked after him. She missed the customary flourish of his stick; she saw his little Scotch terrier, who had run out at his heels, barking and capering about him unnoticed. He was out of spirits: he was strangely out of spirits. What did it mean? [Chapter IX: 240 in serial, pp. 41-42 in volume as the chapter's tailpiece]

Commentary: The Focus on Mr. Andrew Vanstone's Dilemma in Confronting Mr. Clare

However will he break the news to his misanthropic neighbour and friend that their children are in love with one another, and wish to marry? Obviously, Andrew Vanstone, clearly shocked by his daughter's sudden revelation, will have to confront Frank's father without Magdalen present: hence, the last-minute instruction about wearing a hat in the garden. Thus, she does not even appear in the vignette. In terms of visual continuity, Maclenan wished to focus on a single character again here, just as he has done in the previous vignettes, each of which features a character who will prove instrumental in the forthcoming weekly instalment. Placing the father in the sole company of his dutiful terrier, in psychological as well as physical isolation as he traverses the grounds of his estate towards Clare's cottage, the artist underscores the father's dilemma: Mr. Vanstone is not sure what sort of reception his news of romance and marriage will receive, although such will cement the lifelong friendship between the ebullient optimist and the cynical philosopher. We can readily read his stupefaction in the main illustration as he consoles his overwrought younger daughter, but even from his posture we cannot read his mood as we cannot see his face. We know that the figure in the tweed suit must be Andrew Vanstone for it is what he wears in the main plate, and because in the text he is habitually in the company of his terrier when outdoors.

The two garden plates taken in conjunction with each other graph the romantic complication with which Magdalen, free of the constraints and prying ears of the great house, has just presented her father in Chapter IX. However, in both plates Maclenan places the emphasis upon the shocked father rather than the distressed daughter. After all, although she certainly likes Francis Clare, and has done so since childhood, the fond parent has never before contemplated the possibility of having feckless Frank as a son-in-law. Andrew Vanstone, doting but rather obtuse father, must suddenly consider Frank as a possible husband and provider for his younger daughter — and even as the father of his grandchildren — an insecure twenty-year-old without prospects. Moreover, if he is going to avert the possibility of Frank's being sent off to an obscure British trading port in coastal China, he must have a candid conversation with the lad's misanthropic parent. Clearly he is not looking forward to this conversation.

Related Material, Including Trade with China

- Frontispiece to Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1864) by John Everett Millais

- Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages

- Wilkie Collins's No Name (1862): Charles Dickens, Sheridan's The Rivals, and the Lost Franklin Expedition

- Henry Morley, "Our Phantom Ship: China

- The Mysteries of Edwin Drood and the Chinese Opium Wars

- England and China: The Opium Wars, 1839-60

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.