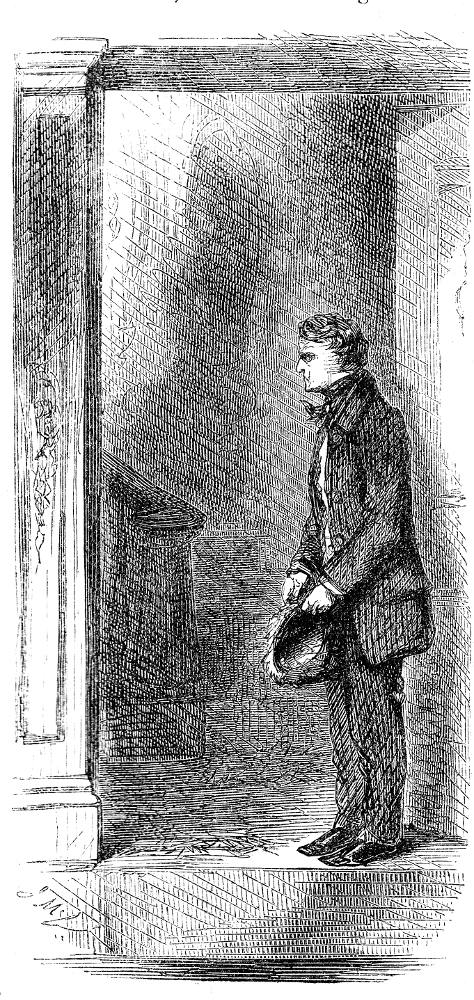

As she realizes that she may have overstepped her role as disciplinarian with Magdalen, Miss Garth apologizes to her charge in acknowledgement of the girl's engagement in “Consider me for the future, if you please, as an obstacle removed.” — the accompanying headnote vignette for "The First Scene," Chapter X, which involves the unexpected appearance of a railway employee with ill tidings, in Wilkie Collins's No Name, first published in All the Year Round and Harper's Weekly (Vol. VI-No. 274), Number 56 (the 19 April 1862 instalment); vignette: 11.5 cm high by 5.7 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted; with the smaller and regular illustrations both appearing on p. 253 in the serial). The main plate, also a wood-engraving, appears at the bottom of the folio page in the serial: 11.7 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed; top of p. 43 in volume's Chapter X. These two illustrations are positioned on different pages in the volume: p. 46 for the vignette within Chapter X.

Comic Passage Realised in the Main Plate: Miss Garth Guardedly Apologizes to Magdalen

“Pray accept my congratulations,” said Miss Garth, bristling all over with implied objections to Frank — “my congratulations, and my apologies. When I caught you kissing Mr. Francis Clare in the summer-house, I had no idea you were engaged in carrying out the intentions of your parents. I offer no opinion on the subject. I merely regret my own accidental appearance in the character of an Obstacle to the course of true-love — which appears to run smooth in summer-houses, whatever Shakespeare may say to the contrary. Consider me for the future, if you please, as an Obstacle removed. May you be happy!” Miss Garth’s lips closed on that last sentence like a trap, and Miss Garth’s eyes looked ominously prophetic into the matrimonial future. [Chapter 10, p. 253 in serial; p. 42 in volume]

Headnote Vignette: Just as Things for Magdalen and Frank are looking up, tragedy strikes.

The man stood just inside the door, on the mat. His eyes wandered, his face was pale — he looked ill; he looked frightened. He trifled nervously with his cap, and shifted it backward and forward, from one hand to the other.

“You wanted to see me?” said Miss Garth.

“I beg your pardon, ma’am. — You are not Mrs. Vanstone, are you?”

“Certainly not. I am Miss Garth. Why do you ask the question?”

“I am employed in the clerk’s office at Grailsea Station —”

“Yes?”

“I am sent here —”

He stopped again. His wandering eyes looked down at the mat, and his restless hands wrung his cap harder and harder. He moistened his dry lips, and tried once more.

“I am sent here on a very serious errand.”

“Serious to me?”

“Serious to all in this house.”

Miss Garth took one step nearer to him — took one steady look at his face. She turned cold in the summer heat. “Stop!” she said, with a sudden distrust, and glanced aside anxiously at the door of the morning-room. It was safely closed. “Tell me the worst; and don’t speak loud. There has been an accident. Where?”

“On the railway. Close to Grailsea Station.”

“The up-train to London?”

“No: the down-train at one-fifty —”

“God Almighty help us! The train Mr. Vanstone traveled by to Grailsea?”

“The same. I was sent here by the up-train; the line was just cleared in time for it. They wouldn’t write — they said I must see ‘Miss Garth,’ and tell her. There are seven passengers badly hurt; and two —”

The next word failed on his lips; he raised his hand in the dead silence. With eyes that opened wide in horror, he raised his hand and pointed over Miss Garth’s shoulder.

She turned a little, and looked back.

Face to face with her, on the threshold of the study door, stood the mistress of the house. She held her old music-book clutched fast mechanically in both hands. She stood, the specter of herself. With a dreadful vacancy in her eyes, with a dreadful stillness in her voice, she repeated the man’s last words:

“Seven passengers badly hurt; and two —”

Her tortured fingers relaxed their hold; the book dropped from them; she sank forward heavily. Miss Garth caught her before she fell — caught her, and turned upon the man, with the wife’s swooning body in her arms, to hear the husband’s fate.

“The harm is done,” she said; “you may speak out. Is he wounded, or dead?”

“Dead.” [Chapter 10, p. 254 in serial; p. 46 in volume]

Commentary: Mixed Emotions in the Sixth Serial Instalment

We now suddenly and shockingly move to the turning point in the fortunes of the Vanstones. Even as Mr. Vanstone has made it possible for Frank to remain in a commercial office in London rather than spend five years in China, and Miss Garth has apologised for her intemperate criticism of the apparently engaged girl's conduct with Frank, both parents suddenly die. The vignette concerns the bearer of the ill-tidings of Andrew Vanstone's being killed in a railway accident just hours before the late afternoon scene at Combe-Raven. Thus, Collins utilizes the chief negative aspect of the Transportation Age, the railway disaster ("a scene of agony and bewilderment as, happily, is but rarely witnessed," ILN, 17 June 1865) to advance his plot.

By describing in detail Mrs. Vanstone's languor and feebleness extensively, Collins has prepared readers for her untimely death. However, at the curtain of the sixth serial instalment the railway company's messenger brings news of a tragic rail accident in which the father of the bride has been killed. The messenger's rigid posture and sour-faced expression distinguish him from the other professionally dressed young man, Francis Clare, and render him a suitable emissary for death. In taking a short trip by rail to perform an act of charity for a former employee (now the miller at Grailsea), Mr. Vanstone has perished in a freak accident. His enfeebled wife, stricken with grief, will die shortly after receiving the news, leaving the daughters to deal with the financially disastrous news from their parents' attorney, Mr. Pendril: as their parents were not legally married when either girl was born, the daughters are not "Vanstones" at all, and cannot inherit the Somersetshire estate. They have been left penniless orphans. And now comes the Sensational revelation of the true purpose of that mysterious London trip: the parents had secretly married. They had never been able to marry before because he had still been legally married to a woman from New Orleans, recently deceased. All of this unsettling news prepares readers for the fact that a selfish uncle will successfully contest the girls' legitimacy and steal their inheritance.

Related Material, Including Matters of Female Inheritance and Railway Disasters

- Frontispiece to Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1864) by John Everett Millais

- Victorian Paratextuality: Pictorial Frontispieces and Pictorial Title-Pages

- Wilkie Collins's No Name (1862): Charles Dickens, Sheridan's The Rivals, and the Lost Franklin Expedition

- "The Law of Abduction": Marriage and Divorce in Victorian Sensation and Mission Novels

- Gordon Thomson's A Poser from Fun (5 April 1862)

- Kate Egan's Playthings to Men: Women, Power, and Money in Gaskell and Trollope

- Philip V. Allingham, The Victorian Sensation Novel, 1860-1880 — "preaching to the nerves instead of the judgment"

- Charles Dickens Relieving the Sufferers at the Fatal Railway Accident Near Staplehurst (24 June 1865)

- Train wrecks, other disasters, and danger on the rails (1830-77)

- The Rednal train wreck on the Shrewsbury and Chester Line (1860)

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.