“If you ever let him faint, you let him die.” Wood-engraving 11.3 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed, for instalment thirty-four in the American serialisation of Wilkie Collins’s No Name in Harper’s Weekly [Vol. VI. — No. 305] Number 34, “The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter I, (page 702; p. 211 in volume), plus an uncaptioned vignettte of Noel Vanstone at the garden gate (Chapter I: p. 638; p. 207 in volume): 9.6 cm high by 5.6 cm wide, or 4 inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted. [Instalment No. 34 ends in the American serialisation on page 703, at the end of Chapter I. Precisely the same number containing just Chapter I without any illustration ran on 1 November 1862 in All the Year Round.]

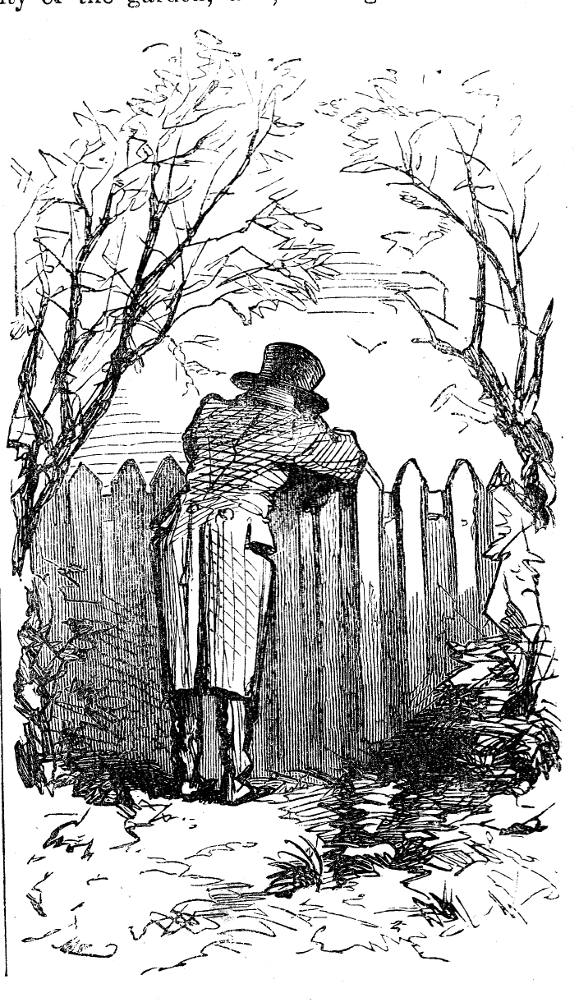

Vignette Illustration: Noel Vanstone at the Garden Gate

“Have you seen the sun yourself on the garden?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Get me my great-coat; I’ll take a little turn. Has the man brushed it? Did you see the man brush it yourself? What do you mean by saying he has brushed it, when you didn’t see him? Let me look at the tails. If there’s a speck of dust on the tails, I’ll turn the man off! — Help me on with it.”

Louisa helped him on with his coat, and gave him his hat. He went out irritably. The coat was a large one (it had belonged to his father); the hat was a large one (it was a misfit purchased as a bargain by himself). He was submerged in his hat and coat; he looked singularly small, and frail, and miserable, as he slowly wended his way, in the wintry sunlight, down the garden walk. The path sloped gently from the back of the house to the water side, from which it was parted by a low wooden fence. After pacing backward and forward slowly for some little time, he stopped at the lower extremity of the garden, and, leaning on the fence, looked down listlessly at the smooth flow of the river. [“The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter I: p. 638; pp. 207-208 in volume]

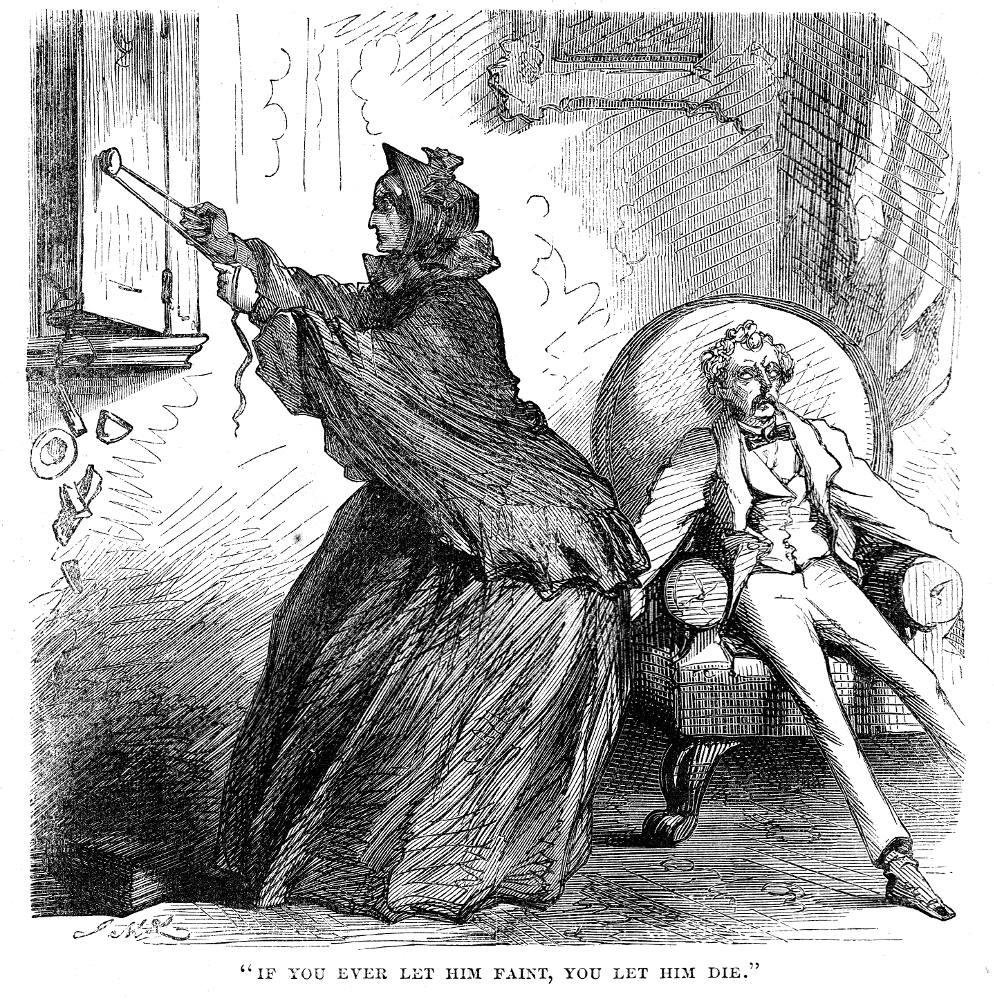

Main Illustration: Mrs. Lecount’s Restoring Noel Vanstone to Life

The dress dropped from his hands, and the deadly bluish pallor — which every doctor who attended him had warned his housekeeper to dread — overspread his face slowly. Mrs. Lecount had not reckoned on such an answer to her question as she now saw in his cheeks. She hurried round to him, with the smelling-bottle in her hand. He dropped to his knees and caught at her dress with the grasp of a drowning man. “Save me!” he gasped, in a hoarse, breathless whisper. “Oh, Lecount, save me!

“I promise to save you,” said Mrs. Lecount; “I am here with the means and the resolution to save you. Come away from this place — come nearer to the air.” She raised him as she spoke, and led him across the room to the window. “Do you feel the chill pain again on your left side?” she asked, with the first signs of alarm that she had shown yet. “Has your wife got any eau-de-cologne, any sal-volatile in her room? Don’t exhaust yourself by speaking — point to the place!”

He pointed to a little triangular cupboard of old worm-eaten walnut-wood fixed high in a corner of the room. Mrs. Lecount tried the door: it was locked.

As she made that discovery, she saw his head sink back gradually on the easy-chair in which she had placed him. The warning of the doctors in past years — “If you ever let him faint, you let him die” — recurred to her memory as if it had been spoken the day before. She looked at the cupboard again. In a recess under it lay some ends of cord, placed there apparently for purposes of packing. Without an instant’s hesitation, she snatched up a morsel of cord, tied one end fast round the knob of the cupboard door, and seizing the other end in both hands, pulled it suddenly with the exertion of her whole strength. The rotten wood gave way, the cupboard doors flew open, and a heap of little trifles poured out noisily on the floor. Without stopping to notice the broken china and glass at her feet, she looked into the dark recesses of the cupboard and saw the gleam of two glass bottles. One was put away at the extreme back of the shelf, the other was a little in advance, almost hiding it. She snatched them both out at once, and took them, one in each hand, to the window, where she could read their labels in the clearer light. [“The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter I: p. 638; pp. 211-212 in volume]

Commentary: Mrs. Lecount's Triumphing over the absent Magdalen at Balliol Cottage

Having hastily returned from Zurich when she learned upon arrival that her brother was quite well and that the physician’s letter announcing his relapse was a forgery, Mrs. Lecount has been very ill. She has, however, recovered enough to track her master and his new wife to a cottage in Scotland on the shores of the Nith on the morning of November 3rd, 1847. And coincidence now favours her, for the new Mrs. Vanstone has just departed earlier that morning for London. Once more, Virginie Lecount seems to have naive Noel Vanstone (lamenting his poor health and trying domestic circumstances in the vignette) in her power.

In the main illustration, Mrs. Lecount has just used the piece of Alpaca dress (taken in his sight from her travelling bag) to prove conclusively that the woman disguised as Miss Garth earlier at Vauxhall Walk was indeed Magdalen, for the piece of shorn fabric fits perfectly beneath the flounce on the Alpaca dress in Mrs. Vanstone’s closet — the cunning housekeeper has even ensured that her master has brought the dress forth with his own hands. Her victory over her adverse circumstances seems conclusive when, having rescued the master form a choking fit, she finds the bottle marked “Poison” by the local chemist in Magdalen’s locked cupboard (upper left) as she searches for restorative smelling salts. Thus, both by good planning and by sheer coincidence, she has been able to convince her master that his new wife means to murder him. Collins’s use of the word “POISON” (p. 212 in volume) in block capitals as the final word for the first chapter in “The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries,” is a master-stroke.

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.