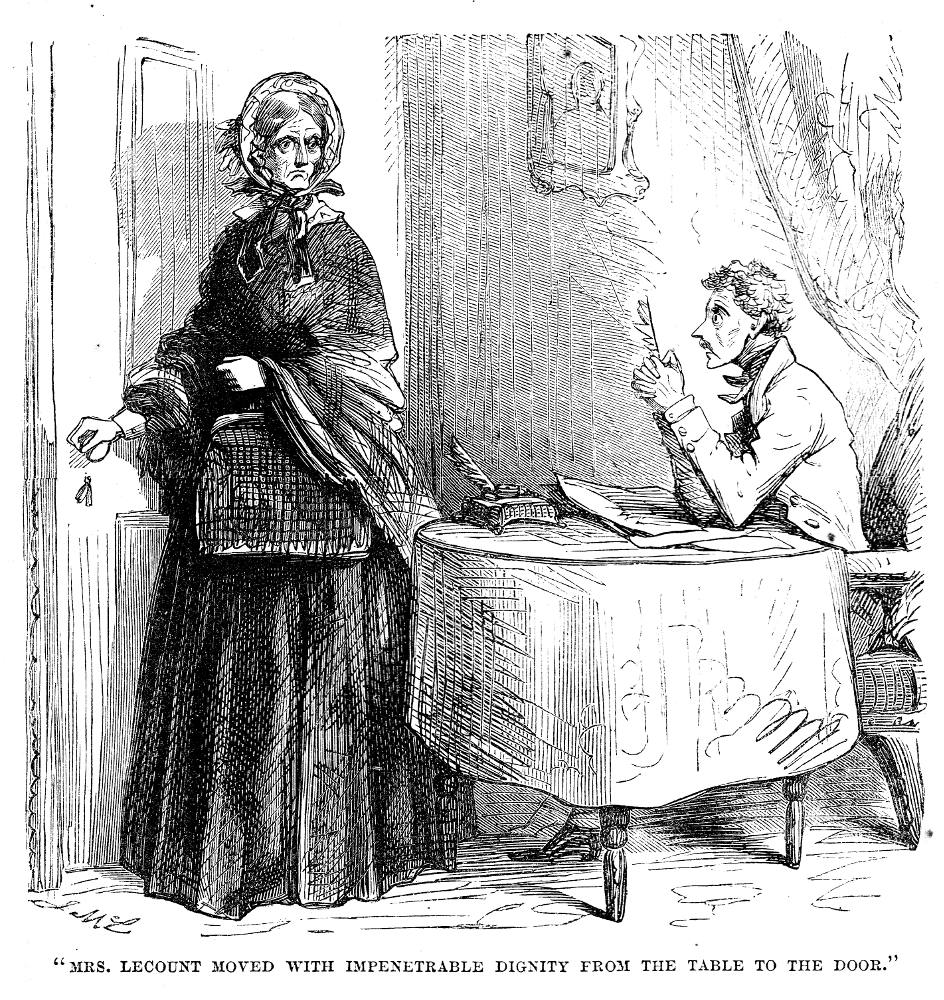

Mrs. Lecount moved with impenetrable dignity from the table to the door. Wood-engraving 11.3 cm high by 11.5 cm wide, or 4 ½ inches square, framed, for instalment thirty-five in the American serialisation of Wilkie Collins’s No Name in Harper’s Weekly [Vol. VI. — No. 306] Number 35, “The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter II, (page 714; p. 217 in volume), plus an uncaptioned vignettte of Mrs. Lecount and Noel Vanstone (Chapter II: p. 714; p. 217 in volume): 9.6 cm high by 5.6 cm wide, or 4 inches high by 2 ¼ inches wide, vignetted. [Instalment No. 35 ends in the American serialisation on page 715, at the end of Chapter II. Precisely the same number containing Chapters I and II without any illustration ran on 8 November 1862 in All the Year Round.]

Vignette Illustration: Noel Vanstone believes that Magdalen means to poison him

There the bottle lay, in Magdalen’s absence, a false witness of treason which had never entered her mind—treason against her husband’s life!

With his hand still mechanically pointing at the table Noel Vanstone raised his head and looked up at Mrs. Lecount.

“I took it from the cupboard,” she said, answering the look. “I took both bottles out together, not knowing which might be the bottle I wanted. I am as much shocked, as much frightened, as you are.”

“Poison!” he said to himself, slowly. “Poison locked up by my wife in the cupboard in her own room.” He stopped, and looked at Mrs. Lecount once more. “For me?” he asked, in a vacant, inquiring tone.

“We will not talk of it, sir, until your mind is more at ease,” said Mrs. Lecount. [“The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter II: p. 714; p. 212 in volume]

Main Illustration: Mrs. Lecount’s Confronting Her Employer about His Bequest to Her

She looked at her watch, and relapsed into silence. He clinched his hands, and writhed from side to side of his chair in an agony of indecision. Mrs. Lecount passively refused to take the slightest notice of him.

“What should you say — ?” he began, and suddenly stopped again.

“Yes, sir?”

“What should you say to — a thousand pounds?”

Mrs. Lecount rose from her chair, and looked him full in the face, with the majestic indignation of an outraged woman.

“After the service I have rendered you to-day, Mr. Noel,” she said, “I have at least earned a claim on your respect, if I have earned nothing more. I wish you good-morning.”

“Two thousand!” cried Noel Vanstone, with the courage of despair.

Mrs. Lecount folded up her papers and hung her traveling-bag over her arm in contemptuous silence.

“Three thousand!”

Mrs. Lecount moved with impenetrable dignity from the table to the door.

“Four thousand!”

Mrs. Lecount gathered her shawl round her with a shudder, and opened the door.

“Five thousand!”

He clasped his hands, and wrung them at her in a frenzy of rage and suspense. “Five thousand” was the death-cry of his pecuniary suicide. [“The Fifth Scene, Baliol Cottage, Dumfries.” Chapter II: p. 714; p. 216 in volume]

Commentary: The Insidious Bottle of Laudanum Marked “Poison” by the Chemist

Before her marriage to the odious Noel Vanstone, her cousin who has usurped her inheritance, Magdalen (pleading the need to relieve the pain of a toothache) had purchased a bottle of laudanum at the local chemist’s shop as a possible means of escaping becoming Mrs. Noel Vanstone. This is the very bottle prominently positioned on the window ledge in Sir John Everett Millais’ Frontispiece for the 1864 triple-decker of the novel published by Sampson, Low in London. It is the focal point of her debate as to whether to commit suicide or proceed with her plan to regain her inheritance through the spurious marriage. Here, however, while Magdalen is away in London, Mrs. Lecount triumphs. Noel Vanstone's gratitude to her for saving his life leads to her negotiating a bequest from his estate of five thousand pounds.

Magdalen Vanstone’s disguise, assumed name, and identity; the bottle marked “Poison” (but in fact laudanum); and the solution offered by Noel Vanstone’s death (by which Magdalen’s claim to the estate would have withstood any legal challenge) are entirely consistent with the narrative strategies of the Sensation novel. As Gail Marshall notes, the construction of identity, particularly female identity, was crucial in such works as Collins’s No Name (1863), Moonstone (1868). “Mistaken identity, hidden identities, are the staples of Collins’s No Name (1862) and Armadale (1866), and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley's Secret (1862), and are often concerned with questions of inheritance, with legal identity, but the language of psychology allowed other dimensions of the question to be addressed” (58-59). The features commonly associated with the Sensation Novel (many of which are evident at this point in No Name) include the following, except the typical Collinsian “aristocratic villain,” for the crafty and determined Virginie Lecount is hardly either male or upper class:

Related Material

Image scans and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Blain, Virginia. “Introduction” and “Explanatory Notes” to Wilkie Collins's No Name. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.