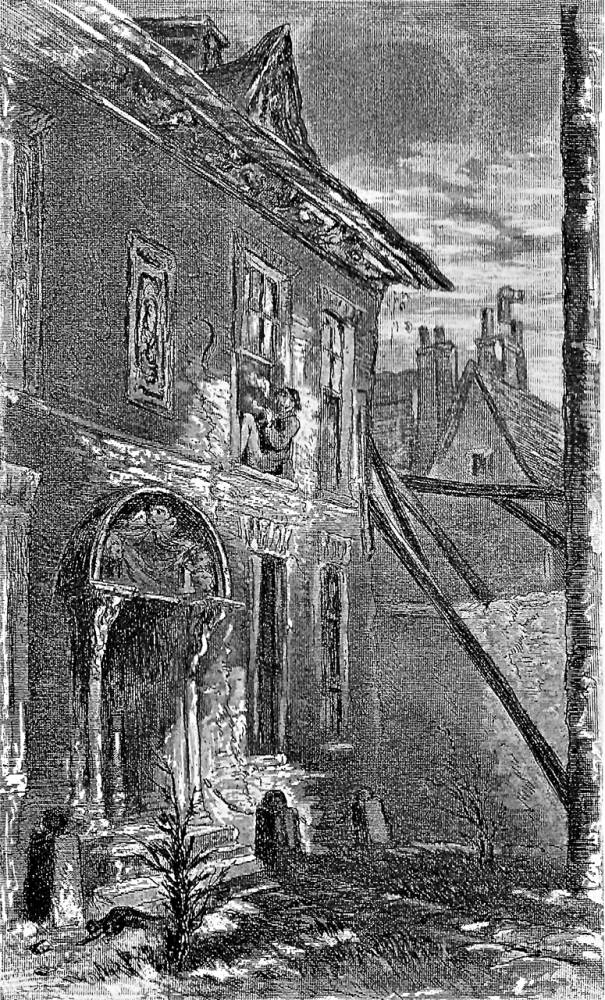

The sun had set, and the streets were dim in the dusky twilight, when the figure, so long unused to them, hurried on its way — Book 2, chap. xxxi, is the full title as given in both the Harper and Brothers and the Chapman and Hall editions, directing readers to the opening paragraphs of Chapter 31. This is Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fifty-fifth composite woodblock illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high by 13.5 cm wide, p. 393, framed, under the running head "Mrs. Affery's Dreams." [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

The sun had set, and the streets were dim in the dusty twilight, when the figure so long unused to them hurried on its way. In the immediate neighbourhood of the old house it attracted little attention, for there were only a few straggling people to notice it; but, ascending from the river by the crooked ways that led to London Bridge, and passing into the great main road, it became surrounded by astonishment.

Resolute and wild of look, rapid of foot and yet weak and uncertain, conspicuously dressed in its black garments and with its hurried head-covering, gaunt and of an unearthly paleness, it pressed forward, taking no more heed of the throng than a sleep-walker. More remarkable by being so removed from the crowd it was among than if it had been lifted on a pedestal to be seen, the figure attracted all eyes. Saunterers pricked up their attention to observe it; busy people, crossing it, slackened their pace and turned their heads; companions pausing and standing aside, whispered one another to look at this spectral woman who was coming by; and the sweep of the figure as it passed seemed to create a vortex, drawing the most idle and most curious after it. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 31, "Closed," p. 388.

Commentary

Acting under the instructions of the novelist, the original Phiz engraving for the monthly "double" number (June 1857) in which this chapter was situated did not disclose any twists of the convoluted inheritance plot, merely telegraphing to the astute reader that something dire might befall the Clennam house in Damocles (Chapter 30). In the Household Edition, however, Mahoney generates considerable suspense by letting the reader know in advance of the relevant passage that Mrs. Clennam has risen from her wheelchair for the first time in fifteen years. What has impelled her to do so, however, the reader will shortly discover as Rigaud and Mrs. Clennam reveal various plot secrets, including the fact that Jeremiah Flintwinch had entrusted the documents pertaining to Little Dorrit's inheritance to his twin brother, who took them to Antwerp, where, after making Rigaud's acquaintance, he suddenly died, leaving Rigaud in possession of them. At the conclusion of these revelations, Mrs. Clennam, determined to prevent Arthur from reading the contents of the package that Rigaud has delivered to Amy at the Marshalsea, rises in order to reach the prison before the gates shut at sunset:

"My angel," said Rigaud, "I have said what I will take, and time presses. Before coming here, I placed copies of the most important of these papers in another hand. Put off the time till the Marshalsea gate shall be shut for the night, and it will be too late to treat. The prisoner will have read them."

She put her two hands to her head again, uttered a loud exclamation, and started to her feet. She staggered for a moment, as if she would have fallen; then stood firm.

"Say what you mean. Say what you mean, man!"

Before her ghostly figure, so long unused to its erect attitude, and so stiffened in it, Rigaud fell back and dropped his voice. It was, to all the three, almost as if a dead woman had risen. — Book the Second, Riches," Chapter 30, "Closing In," p. 403.

In Mahoney's illustration for the ensuing page, her head wrapped in a shawl she has grabbed from her closet, Mrs. Clennam has left her decaying mansion and ventured into the streets, from the byways to the main thoroughfare and across London Bridge into the Borough, down a street immediately by the Thames, looking for the debtors' prison. Instead of a pack of street-boys taunting her, as in Harry Furniss's 1910 lithograph Mrs. Clennam seeks Little Dorrit (Chapter 31), Mahoney has an alehouse waitress and a corpulent adolescent (upper centre) stare at her quizzically as she unsteadily makes her way down the centre of the thoroughfare. The waste-ground behind Mrs. Clennam seems a suitable comment on her derelict state.

Embedded in the illustration is what amounts to an advertisement for Burton's Ale, a product not of London, but an India Pale Ale brewed in the north, at Burton-on-Trent, from the eighteenth through the nineteenth centuries and exported all over the country, first by barge and then by rail. Made with just pale malt and Golding hops, the ale had a russet brown colour, bitter-sweet, almost fruity taste, and an alcoholic content of up to 10.5%, making it a favourite in the capital — and as far away as Russia, where both Catherine the Great and Peter the Great were avid imbibers, before the Napoleonic Wars curtailed Burton's as a British export. In the 1850s a French foodie named Payer asserted that the bitterness of the brew was derived from strychnine, prompting the Burton brewers to subject their wares to public scrutiny and analysis. It may be this imbroglio to which James Mahoney is alluding in the picture of the witch-like villainess haltingly making her way to confess to Amy Dorrit the role she has played in depriving her of her inheritance for so many years, and to prevent Amy's giving the Arthur the papers that explain his illegitimate birth.

Relevant Illustrations, 1857 through 1910

Left: Phiz's original serial illustration for the lkat, "double" number, showing Rigaud calmly smoking as the house is about to collapse, Damocles (Ch. 30). Centre: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's title-page vignette depicting the meeting in Mrs. Clennam's room of Affery, Flintwinch, Mrs. Clennam, and Rigaud, Closing In — Book II, Ch. XXX (1863). Right: Harry Furniss's illustration of the witch-like Mrs. Clennam, getting lost as she tries to find the Marshalsea, Mrs. Clennam seeks Little Dorrit (1910). [Click the on the images to enlarge them.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Ch. 12, "Work, Work, Work." Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 128-160.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 17 June 2016