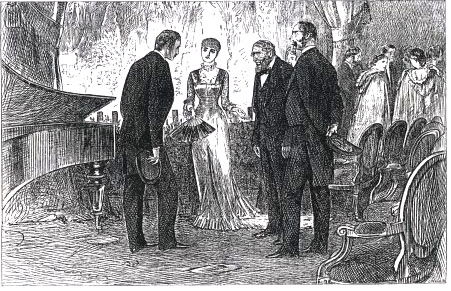

My Uncle, Mr. Abner Power, Said Paula by George Du Maurier for Harper's New Monthly Magazine (1880).

Episode 8, as Jackson points out, is introduced by a mediocre illustration (Book III, Ch. 10), but would be better introduced by a realisation of the moment when de Stancy appears to kiss Paula in the production of Love's Labours Lost. Instead, Du Maurier destroys any suspense that Hardy was able to generate through the mysterious stranger, although the true source of suspense admittedly is not the peculiar character's identity so much as his motives in bribing the landlord of the Sleeping-Green to applaud the (apparent) kiss. Like A Laodicean, Love's Labours Lost is a minor comic work in the canon of a great writer; placed at the centre of Hardy's novel, it functions as a subtext in much the same way that Sheridan's The Rivals does in the Sensation novel No Name (1862, by Wilkie Collins, a writer with whose proto-feminist works Hardy was not unfamiliar. The enacting of the play invests the characters with new personalities, leads to new relationships, and causes us to see the principal characters in a new light. That Paula has developed from the daughter of a Baptist who refuses to dance to a young socialite participating in amateur theatricals (albeit for a worthy cause, raising funds for the local hospital) shows the degree to which being mistress of her own fortune and of de Stancy Castle has affected her. That Hardy has taken liberties with Shakespeare's text by implying that Ferdinand, King of Navarre (enacted by de Stancy), who courts the French princess (played by Paul Power), is the protagonist is a distortion in that Berowne, one of Navarre's courtiers, is the male principal; nevertheless, in that the King will fail in his courtship of the princess, despite appearances to the contrary, foreshadows de Stancy's eventual failure to capture Paula's heart.

The King of Navarre's determination to shun the company of women reflects Captain William de Stancy's rejection of past tastes and pleasures that have resulted in his being burdened with an illegitimate son, a determination that he sets aside the instant that he sees the French princess. The comedy's reliance on misdirected letters as the mainstay of the plot, particularly the letter delivered by Jaquenetta that reveals Berowne's guilt, is paralleled in the novel's plot by Havill's copying of Somerset's design for the restoration of the castle, de Stancy's failing to deliver Dare's photograph to the chief constable, and Dare's treated photograph of Somerset. Finally, Paula's continually putting off a formal announcement of her engagement to Somerset parallels the princess's deferring her answer for a year and a day. Although Somerset's labours in love will not be lost, his architectural labours, so closely associated with his relationship with Paula, prove for nought when Dare sets fire to the castle. Dare's efforts on behalf of his father in his suit to Paula and Captain de Stancy's efforts on behalf of his sister to induce Somerset to form a romantic attachment with Charlotte both fail. Finally, throughout the central part of the novel Somerset is convinced that his own labours to win Paula's hand will be lost because she means to set aside her acceptance of him as a lover in favour of Captain de Stancy. Given Somerset's concern about de Stancy's being able to make love to Paula publicly in the amateur production of Love's Labours Lost and of the intertextual meanings conveyed by Hardy's allusions to this comedy, Du Maurier's choice of "Paula's perfunctory introduction of her uncle to Somerset" (Jackson 125) as the subject for his eighth plate was unfortunate from the perspective of narrative-pictorial interest, although the artist has depicted the uncle's introduction with almost photographic realism, filling in the spaces around the four figures with chairs, carpet, a grand piano, and "the knot of friends assembled around Paula . . . discussing the merits and faults of the two days’ performance" (Book III, Ch. 10).

Image scan, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Created 11 May 2001

Last modified 31 December 2019