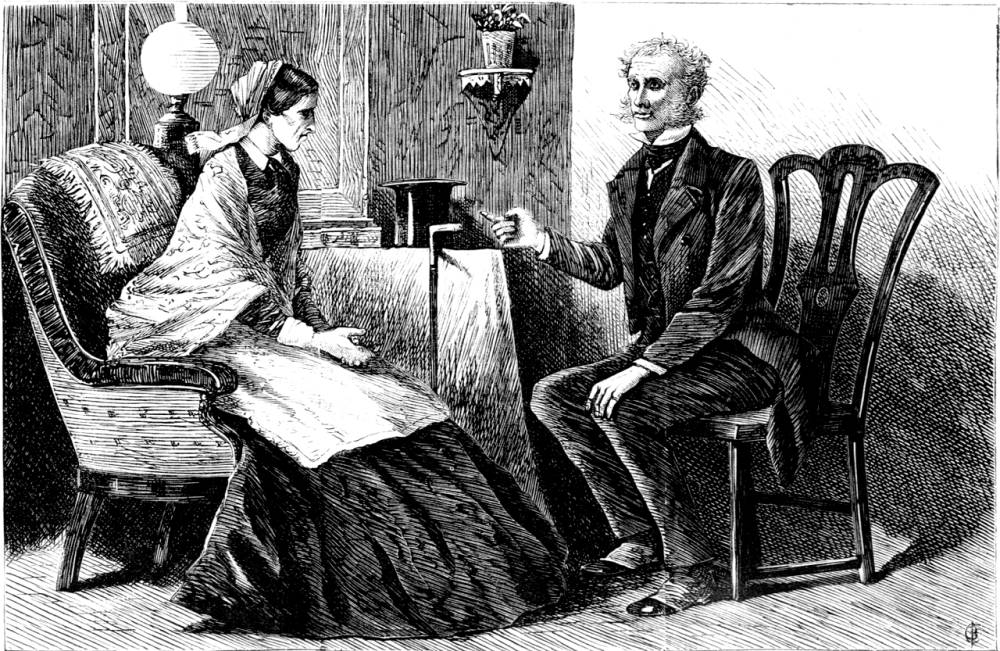

"You are not so good a lawyer, Miss Clack, as I supposed." — second illustration for the sixteenth instalment of Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance. A wood-engraving by Harper & Bros. house illustrator "C. B." 11.2 cm high by 17.4 cm wide. 18 April 1868 instalment in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Chapter 4 in "Second Period. The Discovery of the Truth. 1848-1849.) First Narrative. Contributed by Miss Clack; niece of the late Sir John Verinder," p. 245. [Here, ever the staunch defender of her "christian hero," Godfrey Ablewhite, Miss Clack attempts to prove to the cynical family attorney, Mr. Bruff, that Godfrey could not possibly have stolen the Moonstone, even though Bruff makes a good case against him. The dialogue — and, therefore, the illustration of the pair conversing in the library of the house on Montagu Square, London — is important as it reveals that Godfrey's debts are pressing, whereas those of the second suspect, Franklin Blake, are not.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image and those below without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.] Click on image to enlarge it.

Passage Illustrated: Miss Clack tries to plead Godfrey's innocence with the attorney

I could see plainly that the new light I had thrown on the subject had greatly surprised and disturbed him. Certain expressions dropped from his lips, as he became more and more absorbed in his own thoughts, which suggested to my mind the abominable view that he had hitherto taken of the mystery of the lost Moonstone. He had not scrupled to suspect dear Mr. Godfrey of the infamy of stealing the Diamond, and to attribute Rachel's conduct to a generous resolution to conceal the crime. On Miss Verinder's own authority— a perfectly unassailable authority, as you are aware, in the estimation of Mr. Bruff— that explanation of the circumstances was now shown to be utterly wrong. The perplexity into which I had plunged this high legal authority was so overwhelming that he was quite unable to conceal it from notice. "What a case!" I heard him say to himself, stopping at the window in his walk, and drumming on the glass with his fingers. "It not only defies explanation, it's even beyond conjecture."

There was nothing in these words which made any reply at all needful, on my part — and yet, I answered them! It seems hardly credible that I should not have been able to let Mr. Bruff alone, even now. It seems almost beyond mere mortal perversity that I should have discovered, in what he had just said, a new opportunity of making myself personally disagreeable to him. But— ah, my friends! nothing is beyond mortal perversity; and anything is credible when our fallen natures get the better of us!

"Pardon me for intruding on your reflections," I said to the unsuspecting Mr. Bruff. "But surely there is a conjecture to make which has not occurred to us yet."

"Maybe, Miss Clack. I own I don't know what it is."

"Before I was so fortunate, sir, as to convince you of Mr. Ablewhite's innocence, you mentioned it as one of the reasons for suspecting him, that he was in the house at the time when the Diamond was lost. Permit me to remind you that Mr. Franklin Blake was also in the house at the time when the Diamond was lost."

The old worldling left the window, took a chair exactly opposite to mine, and looked at me steadily, with a hard and vicious smile.

"You are not so good a lawyer, Miss Clack," he remarked in a meditative manner, "as I supposed. You don't know how to let well alone."

"I am afraid I fail to follow you, Mr. Bruff," I said, modestly — Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) First Narrative. Contributed by Miss Clack; niece of the late Sir John Verinder," Ch. IV, p. 246./p>

Commentary

Although Mr. Bruff is obviously her senior and a professional man, Miss Clack has taken the padded chair with the antimacassar, leaving the odious "worldling," Mr. Bruff, the less comfortable chair. Illustrator "C. B." has made neither of them attractive. Bruff is completely sure of himself as he passes judgment on Rachel Verinder's cousins as possible subjects; the more that Miss Clack argues in favour of Godfrey as innocent of the theft, the more the reader is inclined to believe him guilty as the family lawyer (here, an elderly professional man dressed in black and carrying a cane) builds a circumstantial case against him. In the illustration, Miss Clack's downcast look seems to imply that she feels that she has not won the day for her "Christian hero."

Illustrations of Miss Clack from Other Editions, 1868 to 1946

Left: The earlier scene in which Godfrey Ablewhite attempts to comfort Lady Julia and Rachel as Miss Clack (right) looks on admiringly, "She stopped — ran across the room — and fell on her knees at her mother's feet." (fifteenth instalment). Centre: F. A. Fraser's depiction of the same scene, juxtaposing Godfrey Ablewhite and Miss Clack as dispassionate observers of the mother and daughter, "She stopped, ran across the room — and fell on her knees at her mother's feet." (1890). Right: William Sharp's full-page depiction of the sanctimonious poor relation, Miss Clack and Her Diary [uncaptioned] (1946) [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946)

Created 9 September 2016

Last modified 4 November 2025