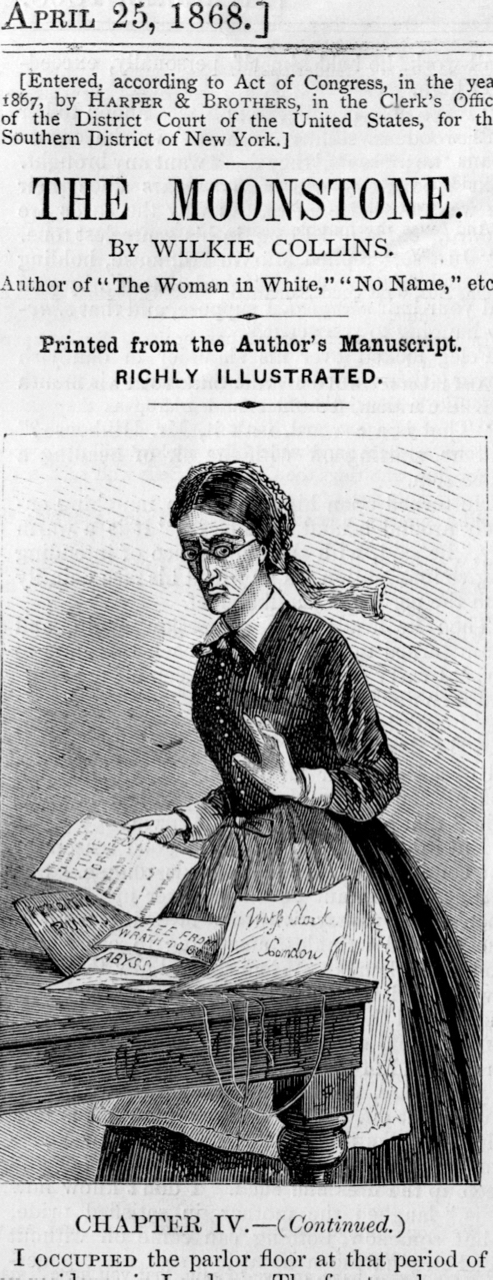

"Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) First Narrative. Contributed by Miss Clack; niece of the late Sir John Verinder." Chapter 4 (Continued) — initial illustration for the seventeenth instalment in Harper's Weekly (25 April 1868), page 261. Wood-engraving, 8.5 x 5.4 cm. [In an effort to effect the spiritual salvation of her wealthy relative and hostess, Lady Julia Verinder, Miss Clack secrets letters in various hands in the family's Montagu Square townhouse.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image and those below without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Seventeenth Instalment

What was to be done now? With my training and my principles, I never had a moment's doubt.

Once self-supported by conscience, once embarked on a career of manifest usefulness, the true Christian never yields. Neither public nor private influences produce the slightest effect on us, when we have once got our mission. Taxation may be the consequence of a mission; riots may be the consequence of a mission; wars may be the consequence of a mission: we go on with our work, irrespective of every human consideration which moves the world outside us. We are above reason; we are beyond ridicule; we see with nobody's eyes, we hear with nobody's ears, we feel with nobody's hearts, but our own. Glorious, glorious privilege! And how is it earned? Ah, my friends, you may spare yourselves the useless inquiry! We are the only people who can earn it — for we are the only people who are always right.

In the case of my misguided aunt, the form which pious perseverance was next to take revealed itself to me plainly enough.

Preparation by clerical friends had failed, owing to Lady Verinder's own reluctance. Preparation by books had failed, owing to the doctor's infidel obstinacy. So be it! What was the next thing to try? The next thing to try was — Preparation by Little Notes. In other words, the books themselves having been sent back, select extracts from the books, copied by different hands, and all addressed as letters to my aunt, were, some to be sent by post, and some to be distributed about the house on the plan I had adopted on the previous day. As letters they would excite no suspicion; as letters they would be opened — and, once opened, might be read. Some of them I wrote myself. "Dear aunt, may I ask your attention to a few lines?" &c. "Dear aunt, I was reading last night, and I chanced on the following passage," &c. Other letters were written for me by my valued fellow-workers, the sisterhood at the Mothers'-Small-Clothes. "Dear madam, pardon the interest taken in you by a true, though humble, friend." "Dear madam, may a serious person surprise you by saying a few cheering words?" Using these and other similar forms of courteous appeal, we reintroduced all my precious passages under a form which not even the doctor's watchful materialism could suspect. Before the shades of evening had closed around us, I had a dozen awakening letters for my aunt, instead of a dozen awakening books. Six I made immediate arrangements for sending through the post, and six I kept in my pocket for personal distribution in the house the next day.

Soon after two o'clock I was again on the field of pious conflict, addressing more kind inquiries to Samuel at Lady Verinder's door.

My aunt had had a bad night. She was again in the room in which I had witnessed her Will, resting on the sofa, and trying to get a little sleep.

I said I would wait in the library, on the chance of seeing her. In the fervour of my zeal to distribute the letters, it never occurred to me to inquire about Rachel. The house was quiet, and it was past the hour at which the musical performance began. I took it for granted that she and her party of pleasure-seekers (Mr. Godfrey, alas! included) were all at the concert, and eagerly devoted myself to my good work, while time and opportunity were still at my own disposal. — "Second period. The Discovery of the Truth. (1848-1849.) First Narrative. Contributed by Miss Clack; niece of the late Sir John Verinder," Ch. IV, p. 261.

Commentary

The headnote vignette describes Miss Clack's producing and acquiring brief letters to effect the spiritual reformation of her aunt, Lady Julia Verinder. Judgmental, overly puritanical, and jealous of her beautiful and wealthy cousin, Rachel Verinder, Miss Drusilla Clack, a poor relation on the Verinder side, is a highly unreliable (and, indeed, as the vignette suggests, devious) observer of events at Montagu Square. She is, in fact, one of Wilkie Collins's most brilliant comic creations in the ironic mode; as Steve Farmer notes in the "Introduction" to the Broadview edition, there is something Dickensian about the sanctimonious, evangelical old maid who resents the young, the beautiful, — and the rich. "Both Ablewhite and Clack . . . play a large role in the novel, but in any discussion of the book, each initiates only very restricted single-track discussions of Collins's abhorence of organized religious hypocrisy" (18). The American illustrator has been unable to resist the urge to make Miss Clack remarkably plain with thick spectacles that imply she is near-sighted.

The headnote vignette specifically identifies Miss Clack as the writer and distributor of morally encouraging "letters" where the dying Lady Julia is likely to find them, a continuation of her distributing moral and "improving" tracts wherever Julia Verinder is likely to find them earlier in Chapter 4. This activity leads directly to her conveniently overhearing Godfrey Ablewhite propose marriage to Rachel Verinder in the adjoining drawing-room on the second floor of the townhouse at Montagu Square when Godfrey assumes she is in the library on the first storey.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions, 1890 to 1946

Left: Godfrey's proposal, delivered with sham romantic conviction, in Alfred Pearse's "I won't even rise from my knees till you have said yes!" (1910). Centre: William Sharp's vignette of Godfrey's rather more perfunctory proposal in the drawing-room, Godfrey on bended knee [uncaptioned] (1946). Right: F. A. Fraser's depiction of Godfrey Ablewhite and Miss Clack earlier as observers of Rachel's devotion to her mother, "She stopped, ran across the room — and fell on her knees at her mother's feet." (1890). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- Illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone: A Romance (1910)

- The 1944 illustrations by William Sharp for The Moonstone (1946)

Created 28 November 2016

Last modified 4 November 2025