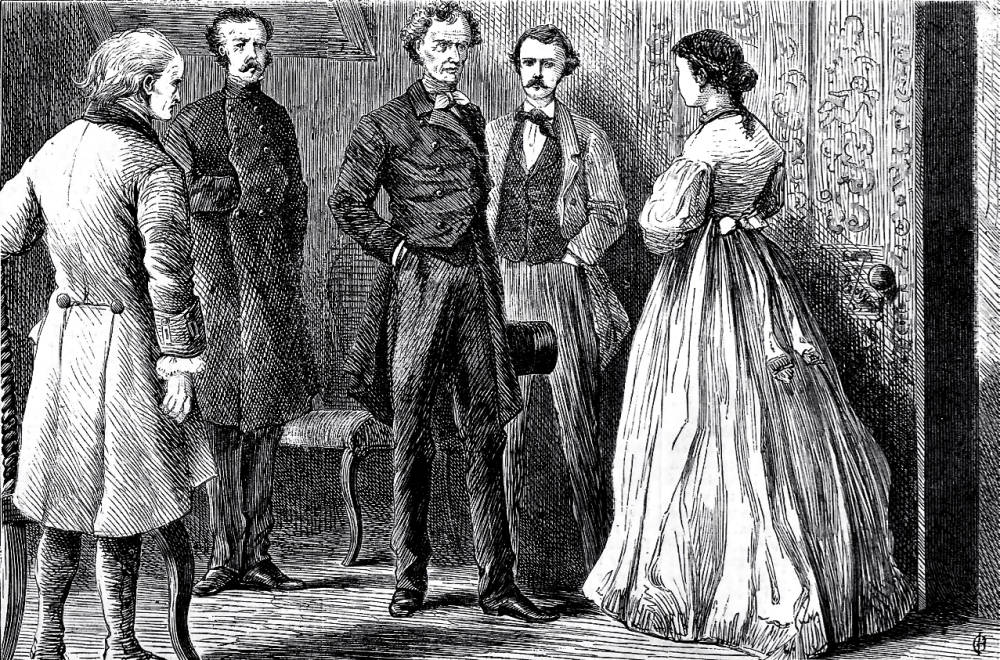

"Sergeant Cuff's immovable eyes never stirred from off her face." — twentieth illustration for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance. A wood-engraving by Harper & Bros. house illustrators; signed "CB." 14.5 cm high by 11.4 cm wide. (4 ¾ by 4 ½ inches). Second illustration for the seventh instalment in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization (15 February 1868). Chapter 12 in "First Period. The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge," p. 101; in volume, p. 58. [Here, for the first time, the celebrated London detective, a police official who studies even the smallest details of a crime scene with a forensic mind-set, interviews Rachel Verinder.] Click on the images to enlarge them.

The serial illustrations here are courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage Illustrated: Cuff's Masterful Interrogation

"Having answered your question, miss," says the Sergeant, "I beg leave to make an inquiry in my turn. There is a smear on the painting of your door, here. Do you happen to know when it was done? or who did it?"

Instead of making any reply, Miss Rachel went on with her questions, as if he had not spoken, or as if she had not heard him.

"Are you another police-officer?" she asked.

"I am Sergeant Cuff, miss, of the Detective Police."

"Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?"

"I shall be glad to hear it, miss."

"Do your duty by yourself — and don't allow Mr Franklin Blake to help you!"

She said those words so spitefully, so savagely, with such an extraordinary outbreak of ill-will towards Mr. Franklin, in her voice and in her look, that — though I had known her from a baby, though I loved and honoured her next to my lady herself — I was ashamed of Miss Rachel for the first time in my life.

Sergeant Cuff's immovable eyes never stirred from off her face. "Thank you, miss," he said. "Do you happen to know anything about the smear? Might you have done it by accident yourself?"

"I know nothing about the smear."

With that answer, she turned away, and shut herself up again in her bed-room. This time, I heard her — as Penelope had heard her before — burst out crying as soon as she was alone again. [This Chapter 12 scene is the also the basis for George Du Maurier's frontispiece in the 1890 Chatto & Windus edition.] — "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder,"Chapter 12, p. 102; volume, pp. 57-58.

Commentary: Meet Detective Sergeant Cuff, Metropolitan Police

Gabriel Betteredge, the aging house-steward to Lady Verinder, the man whose narratives follow the Prologue and precede the Epilogue, is once again the narrator for the bewildering scene in which Rachel Verinder, victim of crime, refuses to cooperate with the investigation. The figures from left to right are as follows: Betteredge (left foreground); in a military-like uniform Superintendent Seegrave of the Frizinghall constabulary; foregrounded, centre, Sergeant Cuff; and dominating the right register in a light dress of period fashion, Rachel Verinder. Thus, the first-personal narrative is translated into a dramatic point-of-view in which the chief antagonists are the highly observant, middle-aged detective and the wilful, young aristocratic heroine, standing in front of the paint-smeared door that has caught Cuff's attention. While his determined facial expression betrays the importance he places upon this clue, the illustrator has turned Rachel's face away from the reader, so that it is difficult to judge how well she is mastering her conflicting feelings. Somehow, the rugged visage of Sergeant Cuff here suggests the lean, weathered face of a western marshall rather than the mild-mannered veneer of Collins's eccentric detective, a figure more accurately conveyed in Du Maurier's less dynamic illustration. Also slightly jarring are Betteredge's continuing to appear wearing livery (in contradiction of Collins's 30 January 1868 instructions to his American publisher) and Franklin Blake's lacking a beard, a mistake that the careful Du Maurier avoided.

The moment that the American illustrator has seized upon — the same moment later selected by George Du Maurier for the frontispiece of The Moonstone: A Romance, illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser (London: Chatto and Windus), underscores eighteen-year-old Rachel Verinder's strength of character and her ability to stand up to a room full of men who are bent on hearing her account of the smeared paint, the cause of which of course she cannot truthfully reveal without implicating Franklin Blake as the thief. In other words, although Rachel's visage is unreadable, in fact she is in the throes of an emotional conflict, having to choose between a highly valuable diamond and the man whom she loves.

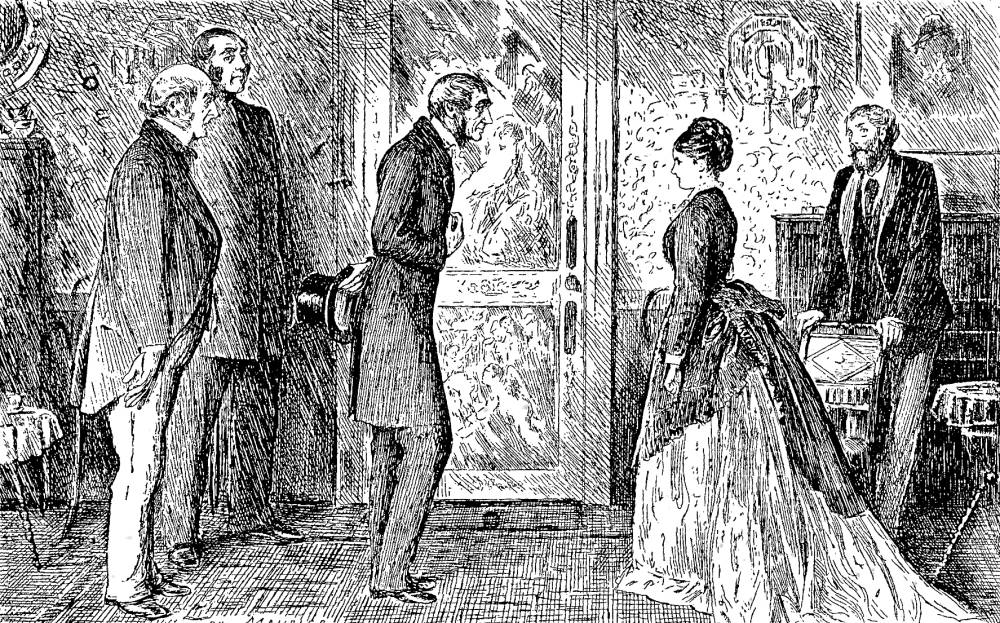

A Relevant Illustration from a Later Edition, 1890 (by George Du Maurier)

Above: George Du Maurier's "New Woman" realisation of the same scene, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" (1890). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." p. 279.

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

- Gallery of Headnote Vignettes by William Jewett for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly (4 January — 8 August 1868)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

________. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York & London: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Gregory, E. R. "Murder in Fact." The New Republic. 22 July 1878, pp. 33-34.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 20 August 2016

Last modified 1 November 2025