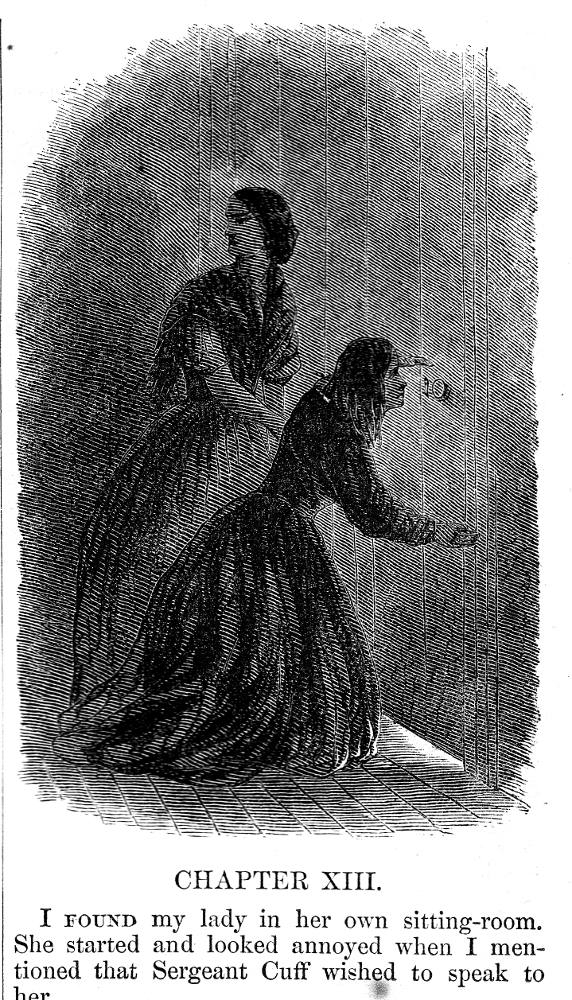

Uncaptioned headnote vignette for "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder." Chapter 13 — initial illustration for the eighth instalment in Harper's Weekly (22 February 1868), p. 117 (p. 60 in volume). Wood-engraving, 8.5 x 5.4 cm. (3 ⅝ by 2 ¼ inches). [The eighth headnote vignette presents two of the other housemaids attempting to spy on Rosanna Spearman, supposedly ill in her room, but in fact on her way to the nearby market-town of Frizinghall. The vignette crystallizes the distrust and antipathy with which the other women servants regard the outsider.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL.]

The illustrations appearing here are courtesy of the E. J. Pratt Fine Arts Library, University of Toronto, and the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia.

Passage suggested by the Headnote Vignette for the Eighth Instalment

The volume edition's rendering of the same wood-engraving, top, p. 60.

My lady's maid and the housemaid, had, it appeared, neither of them believed in Rosanna's illness of the previous day. These two devils — I ask your pardon; but how else can you describe a couple of spiteful women? — had stolen up-stairs, at intervals during the Thursday afternoon; had tried Rosanna's door, and found it locked; had knocked, and not been answered; had listened, and not heard a sound inside. When the girl had come down to tea, and had been sent up, still out of sorts, to bed again, the two devils aforesaid had tried her door once more, and found it locked; had looked at the keyhole, and found it stopped up; had seen a light under the door at midnight, and had heard the crackling of a fire (a fire in a servant's bed-room in the month of June!) at four in the morning. All this they had told Sergeant Cuff, who, in return for their anxiety to enlighten him, had eyed them with sour and suspicious looks, and had shown them plainly that he didn't believe either one or the other. Hence, the unfavourable reports of him which these two women had brought out with them from the examination. Hence, also (without reckoning the influence of the tea-pot), their readiness to let their tongues run to any length on the subject of the Sergeant's ungracious behaviour to them. — Chapter 14, — "First Period: The Loss of the Diamond (1848), The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder,"Chapter 12, p. 118; p.65 in volume.

Commentary

In the previous instalment's vignette, wearing a thick veil obscuring her features entirely, Rosanna Spearman had made her way across a moor, although she was supposedly ill and in her room that afternoon. In this week's instalment, in the middle of the night, two equally obscured maid-servants try to determine as they had earlier in the day whether Rosanna is in her room. Her odd behaviour misleads the reader into suspecting that the lonely, socially isolated reformed criminal is somehow involved in the theft. The conduct of her peers shows that "detective-mania" is infecting the household, and that her fellow servants believe that Rosanna is connected to the paint smears on the door of Rachel Verinder's sitting-room. Leighton and Surridge regard this "dark plate" headnote vignette as part of a pattern of darkness, obscurity, and blindness in the characters that the early headnote vignettes underscore:

Part 1 (fig. 1) initiates the novel's sensational visual motifs, as the chapter head and Herncastle illustration iterate tropes of atmospheric turbulence. The dark smoke from the lamp at the lower left of the chapter head and the roiling smoke from Herncastle’s torch suggest the disturbance that will result when the diamond is stolen from India. As we have already seen, the page layout links this crime of murder to cultural and religious violence; the darkness thus carries ideological significance as well as conveying atmospheric effect. This motif of darkness and mystery is taken up in the dark chapter heads that frame the novel's early instalments. As the mystery unfolds and the diamond disappears, Harper's illustrators used the dark chapter heads to create a visual pattern of darkness and unreadability. These focus on the Indians, whose exaggerated black shadows seem to symbolize nightmarish racialized bodies (fig. 4); on Betteredge guarding the estate, looking into a darkness that we cannot see (fig. 5); and on the women servants, who peep through Rosanna's keyhole, trying fruitlessly to understand her actions (fig. 6). These chapter heads are characterized by deep cross-hatching and very limited white space (none of which illuminates characters' faces). The lack of light on faces suggests the sensation novel's capacity to challenge what we might call common sense — that is, the deeply embedded ideological assumptions about gender, race, and nation that underlie habitual actions. In each of these cases, because the dark illustrations are chapter heads, their brooding atmosphere looms proleptically over the serial part to follow. — Leighton and Surridge, p. 218.

Related Material

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck." p. 279.

- The 1944 Illustrations by William Sharp for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. With sixty-six illustrations by William Jewett. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August 1868, pp. 5-529.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by William Jewett. New York: Harper & Bros., 1871.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone, Parts One and Two. The Works of Wilkie Collins, vols. 5 and 6. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Created 22 November 2016

Last modified 1 November 2025