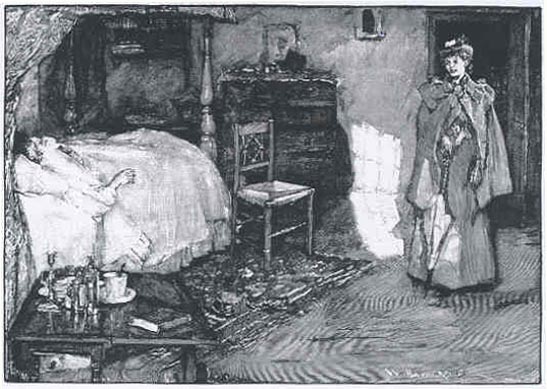

Her advent seemed ghostly — like the flitting in of a moth

William Hatherell

July 1895

17.4 x 12.2 cm

Harper's New Monthly Magazine, XC, p. 818

Scanned image, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> William Hatherell —> Next]

Her advent seemed ghostly — like the flitting in of a moth

William Hatherell

July 1895

17.4 x 12.2 cm

Harper's New Monthly Magazine, XC, p. 818

Scanned image, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham

Reproduced courtesy of Dorset County Council Library Service

The plate accompanying the eighth instalment (July 1895) of Hearts Insurgent in Harper's New Monthly MagazineThe telegraphs the textual moment when Sue, having left Phillotson some weeks before for a curiously platonic relationship with Jude, returns to visit the ailing school-master in Shaston.

After outfacing the villagers and school trustees of Shaston over the supposed immorality of releasing Sue to live wherever she pleases, Richard Phillotson is sickened to witness the verbal and physical altercation between his supporters, the lower-class, itinerant "show-folk," and the respectable denizens of Shaston. Immediately thereafter, he receives his discharge from his post as village school-master, and suffers a mental and physical collapse when he arrives home later that night. The moment illustrated in the eighth plate is Sue's arriving to enquire after her husband's health after receiving an anonymous note in the mail about Phillotson's condition. This letter, penned but unsigned by Phillotson's long-time friend and fellow school-master, Gillingham, was posted care of Jude at Melchester, for Sue's husband is quite unaware that the couple has relocated to the metropolis of Aldbrickham (Reading, Surrey) to assure their anonymity. The letter having been forwarded from Melchester to Shaston, and sent on to Sue by the Widow Edlin in a mere three days (a testimonial on Hardy's part to the efficiency of the Victorian penny-post), Sue arrives at Old-Grove's House via omnibus from the railway station just at sunset, as the intense sunlight on the wall beside her indicates.

In choosing this textual moment for his July illustration Hatherell seems to be underscoring Sue's highly contradictory conduct, for, although she is disgusted by the notion of Phillotson as her lawful husband, she is genuinely concerned about him as a friend and intellectual mentor. The plate does not convey particularly her springtime "lightness," but her layered raincoat does suggest the wing-like structure of a moth -- Hardy's sense in the simile being that she seems drawn towards the destruction of her resolve to live apart from Phillotson by visiting him when he is ill and thereby sympathizing with him. Conscience and sentiment have drawn her to his bedside, exposing her to his heartfelt appeal to have him remain with him in Shaston as his wife in fact. Fearing re-entrapment in a loveless marriage, she hastily departs, pleading the necessity of catching the omnibus to make her uptrain in time to arrive back in Aldbrickham before Jude returns home and begins to worry about her.

The tentativeness of her facial expression in Hatherell's plate prepares us for that look of "incipient fright which showed itself whenever he changed from friend to husband" (Ch. 23). She leaves in ignorance of what has precipitated her husband's collapse, for he does not tell her (perhaps out of a sense that doing so would unfairly persuade her to return to him), and the anonymous note presumably did not disclose the cause of this sudden illness, suggested by the collection of small bottles on the gatelegged bedside table. This and so much else in the room are the artist's inventions -- Hardy describes only the view of the sun setting picturesquely on the Blackmoor Vale (behind the viewer in Hatherell's plate), the bedstead, and the swing-glass that Sue utilizes to cheer Phillotson with the rays of the setting sun. Although the swing-glass is not in our field of vision, the patch of intense sunlight indicates that the window must be immediately behind where the viewer (again, as in a stage set) must be standing. An empty tea-cup, assorted medicine bottles, a candle, and a bible suggest the invalid's present condition and preoccupation with Christian morality. The dark oak gatelegged table and solid chest-of-drawers are consistent with Phillotson's earlier statement that he inherited his parents' oak furniture; moreover, its darkness is consonant with the staid owner's solid character and melacholic disposition. Only his hand and nightshirt-clad arm betray his presence in the July illustration; Sue's form and emotions clearly dominate the plate.

Like Jude, Sue feels some sense of obligation about the welfare of her former spouse, so that the picture establishes a parallel between Sue's visiting Richard and Jude's attempting to assist Arabella earlier. This illustration shows Sue in a more positive light than the other key incidents in the July instalment that the artist might have considered as possible subjects, namely her interview with Arabella in the hotel room (which the present illustration establishes as a parallel to her visiting Phillotson despite her scruples) and Sue's reception of Jude's son by Arabella, "Father Time." At the close of Chapter 36 in the serial, the reader is left to ponder issues directly connected to these events: will Sue finally agree to marry Jude, will she accept the boy as a member of her family despite his physical resemblance to his natural mother, and how will the Fawley marriage curse work itself out if, as we suspect, Sue and Jude do marry?

Hatherell's choosing a less significant moment in the eighth instalment as his subject may have been motivated by a desire to reveal Sue as a conflicted, sympathetic, and yet complicated character, and to avoid revealing the solution to or even overtly alluding to the plot secret (the existence of the boy) that sustains narrative interest through Chapters 35 and 36, that "little matter of business" that has prompted Arabella to seek out Jude.

Hardy, Thomas. Jude the Obscure, ed. Dennis Taylor. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998.

Last modified 16 February 2003