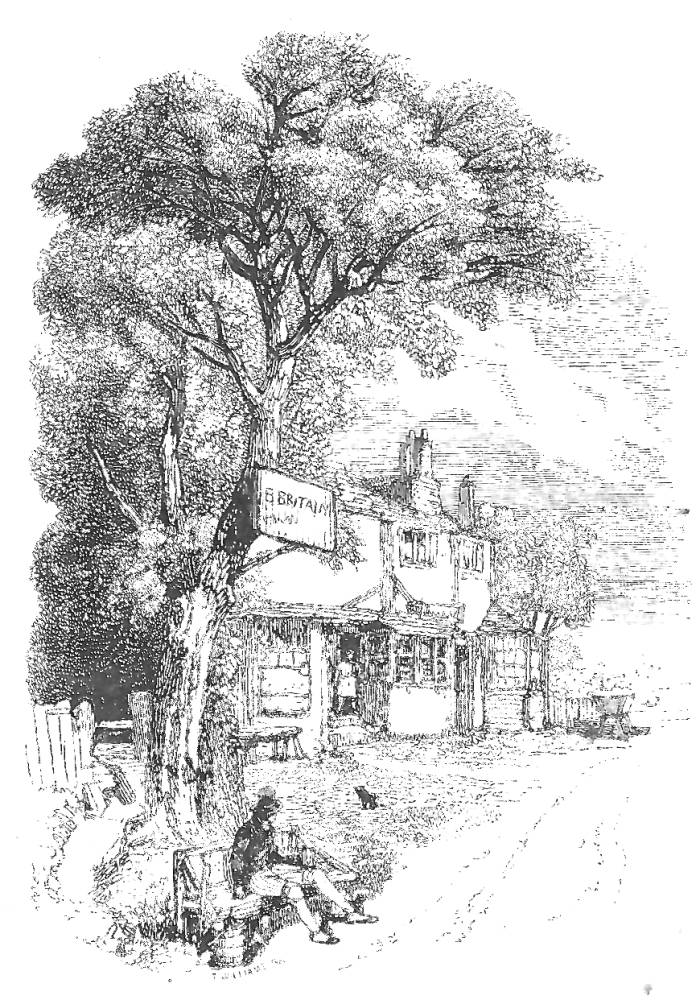

"The 'Nutmeg Grater' Inn" by Charles Green (106). 1893. 9.8 x 15.2 cm, exclusive of frame. Dickens's The Battle of Life, Pears Centenary Edition (1912), in which the plates often have captions that are substantially different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (13-14). Specifically, the caption beneath this illustration is "This village Inn had assumed, on being established, an uncommonsign. It was called The Nutmeg Grater. And underneath that household word was inscribed, up in the tree, on the same flaming board, and in the like golden characters, By Benjamin Britain" (106), the third full page of "Part the Third."

Context of the Illustration

At such a time, one little roadside Inn, snugly sheltered behind a great elm-tree with a rare seat for idlers encircling its capacious bole, addressed a cheerful front towards the traveller, as a house of entertainment ought, and tempted him with many mute but significant assurances of a comfortable welcome. The ruddy sign-board perched up in the tree, with its golden letters winking in the sun, ogled the passer-by, from among the green leaves, like a jolly face, and promised good cheer. The horse-trough, full of clear fresh water, and the ground below it sprinkled with droppings of fragrant hay, made every horse that passed, prick up his ears. The crimson curtains in the lower rooms, and the pure white hangings in the little bed-chambers above, beckoned, Come in! with every breath of air. Upon the bright green shutters, there were golden legends about beer and ale, and neat wines, and good beds; and an affecting picture of a brown jug frothing over at the top. Upon the window-sills were flowering plants in bright red pots, which made a lively show against the white front of the house; and in the darkness of the doorway there were streaks of light, which glanced off from the surfaces of bottles and tankards.

On the door-step, appeared a proper figure of a landlord, too; for, though he was a short man, he was round and broad, and stood with his hands in his pockets, and his legs just wide enough apart to express a mind at rest upon the subject of the cellar, and an easy confidence — too calm and virtuous to become a swagger — in the general resources of the Inn. ["Part the Third," p. 104-105, 1912 edition]

This village Inn had assumed, on being established, an uncommon sign. It was called The Nutmeg-Grater. And underneath that household word, was inscribed, up in the tree, on the same flaming board, and in the like golden characters, By Benjamin Britain. ["Part the Third," 1912 edition, 107]

Commentary

The Nutmeg Grater by Clarkson Stanfield. Click on images to enlarge them.

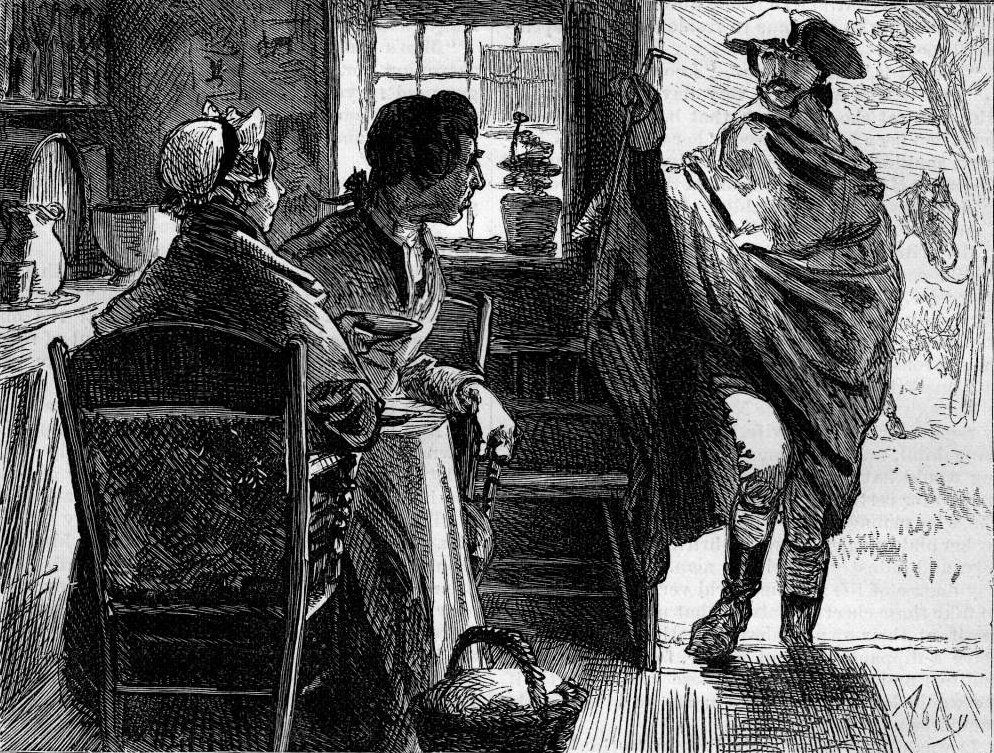

Green had probably studied the equivalent illustration in the 1846 edition by Clarkson Stanfield, an artist who specialized in land- and seascapes. It appears at the very beginning of the second movement of the story to create anticipation in the reader's mind, since the action now jumps ahead a number "five or six years," to a time when Britain, who has left the Doctor's service, has become a publican. Green's strategy resembles Stanfield's. He has provided a picturesque study of the eighteenth-century country inn to signal the fact that theaction now shifts away from the physician's substantial cottage to this more public center of the village. Although Dickens revels in his picturesque description of the rural village inn, few illustrators beyond the team that developed the initial program of illustrations for the 1846 edition have bothered with idyllic, tranquil scene which establishes both a chronological and a geographical context for Michael Warden's returning without Marion Jeddler. In the Household Edition of 1878, Fred Barnard, who had a very limited program of illustration with which to work, does not depict the inn’s exterior but moves directly to the interior scene in which Clemency (now, "Mrs. B.") attempts to alert her obtuse husband to Warden’s arrival: Guessed half aloud "milk and water," "monthly warning," "mice and walnuts" — and couldn't approach her meaning. (see below), a half-page wood-engraving that continues with the comic subtheme that counterpoints the emotional anguish of the principal characters.

Above: E. A. Abbey's 1876 dramatic realisation of the scene in which Michael Warden, a lone traveller on horseback, alights at the inn run by Clemency and Benjamin Britain, A gentleman attired in mourning, and cloaked and booted like a rider on horseback, who stood at the bar-door.

Likewise, E. A. Abbey in the 1876 American Household Edition depicts the publican and his wife Clemency in A Gentleman Attired in Mourning, and Cloaked and Booted like a Rider on Horseback, Who Stood at the Bar-door (see below), in which a tanned, fit-looking stranger with Italianesque mustachios has just alighted from his horse at portal of their inn. These illustrations, then, constitute an elaboration of the chief incident of the opening of "Part the Third," in contrast to Dickens's management of the narrative-pictorial sequence with a plate that merely establishes the scene without giving away the plot incident that follows. In his Charles Dickens Library version of the novella, Harry Furniss carefully avoids hinting at anything that will transpire, showing only a cameo of Marion.

Green establishes the enormous size of the thatched-roofed, two-storeyed inn by the diminutive figure of Britain in his publican's apron, standing just left of centre in the open doorway. Presumably by living frugally and saving a lifetime's wages Benjamin Britain has joined the commercial middle-class, moving from domestic service to what we today refer to as "the hospitality industry." In scope, then, the building as envisaged by Green is not a quaint cottage converted into a roadhouse, as in Stanfield's illustration, but a noble seventeenth-century, half-timbered edifice that is the property of a canny investor who has parlayed servant's wages into a significant investment. Thus, Stanfield's "new picaresque" treatment of The Nutmeg Grater is consistent with Dickens's intention to show how Clemency and Britain have risen moderately in social standing, while Green's painterly treatment of the inn is somewhat exorbitant.

Illustrations for the Other Volumes of the Pears' Centenary Christmas Books of Charles Dickens (1912)

Each contains about thirty illustrations from original drawings by Charles Green, R. I. — Clement Shorter [1912]

- A Christmas Carol (28 plates) Vol. I (1892)

- The Chimes (31 plates) Vol. II (1894)

- L. Rossi's The Cricket on the Hearth (22 plates) Vol. III (1912)

- The Haunted Man (31 plates) Vol. V (1895)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846.

_____. The Battle of Life: A Love Story. Illustrated by John Leech, Richard Doyle, Daniel Maclise, and Clarkson Stanfield. (1846). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. The Battle of Life. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 23 May 2015

Last modified 6 April 2020