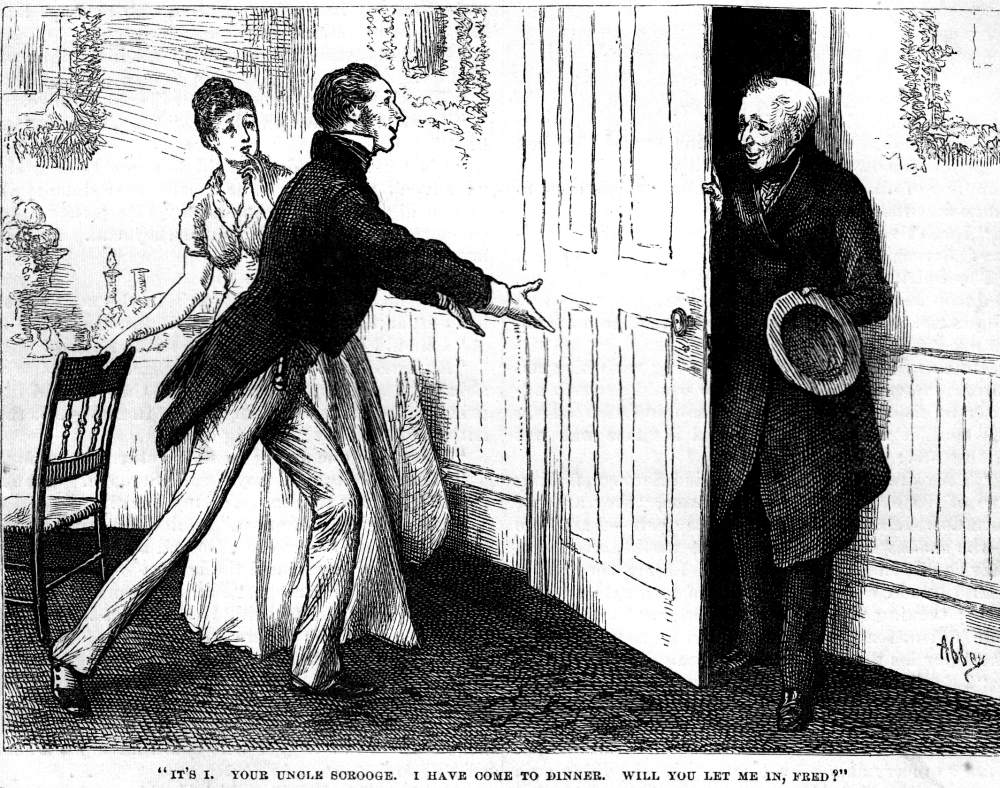

"Scrooge at his Nephew Fred's Christmas Party" by Charles Green (136). 1912. 11 x 13.1 cm, framed. Dickens's A Christmas Carol, Pears Centenary Edition, in which the plates often have captions that are different from the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (p. 15-16). Specifically, Scrooge at his Nephew Fred's Christmas Party has a caption that is quite different from the title given in the "List of Illustrations"; the textual quotation that serves as the caption for this illustration of the gratifying moment when Scrooge receives a warm welcome at his nephew's is "'Why, bless my soul!' cried Fred, 'who's that?' 'It's I. Your uncle Scrooge. I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?'" (136, adapted from the middle of the page preceding the full-page lithograph) in "Stave Five, The End of It."

Context of the Illustration

"Fred!" said Scrooge.

Dear heart alive, how his niece by marriage started. Scrooge had forgotten, for the moment, about her sitting in the corner with the footstool, or he wouldn't have done it, on any account.

"Why bless my soul!" cried Fred," who's that?"

"It's I. Your uncle Scrooge. I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?"

Let him in! It is a mercy he didn't shake his arm off. He was at home in five minutes. Nothing could be heartier. His niece looked just the same. So did Topper when he came. So did the plump sister when she came. So did every one when they came. Wonderful party, wonderful games, wonderful unanimity, won-der-ful happiness! ["Stave Five: The End of It," 135]

Commentary: "Ebenezer Scrooge, Family Man"

Since Dickens tended to derive inspiration from his illustrators' work as they derived inspiration from his, the text and the accompanying illustration The Last of the Spirits together form a climax in the story of Scrooge's spiritual and moral epiphany; the third dimension of his reclamation, the social, is completed in the textual scenes in the fifth and final stave, "The End of It," and in the John Leech tailpiece, Scrooge and Bob Catchit (see below). The visual tradition of the fifth stave is not represented in either Household Edition, the American by E. A. Abbey and the British by Fred Barnard, but is well represented in the twenty-fifth anniversary illustrated edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr.. However, Eytinge does not repeat the party at Fred's, but moves directly from the purchase of the prize turkey to Scrooge's raising Bob's salary on Boxing day.

John Leech provided later illustrators with no model for this scene in the 1843 first edition of the novella, and the single example of a previous illustration of Scrooge's arrival at his nephew's was probably not available to Charles Green, namely an 1876 American Household Edition wood-engraving by E. A. Abbey, "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge! I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?" (see below). However, as a British artist Green simply may not have had access to either this 1876 volume or the Ticknor and Fields volume, published in Boston in late 1868, just after Dickens's second American tour.

Green has admirably contextualised the meeting of the uncle (right) and genial nephew (left), with Fred's wife observing the scene with obvious pleasure rather than concern as in the E. A. Abbey realisation of the same textual moment, Scrooge's being ushered into the dining room, the table in the rear already spread for the party. Whereas in the film adaptations Scrooge hands his coat, hat, and scarf to a maid, in Green's realisation he is still wearing these items. Perhaps Green concluded that this reconcilliation was important because it marks Scrooge's making a visit to a home at Christmas unaccompanied by a spirit guide. He has already been to Fred's accompanied by the Spirit of Christmas Present, although the passage has been illustrated in just one nineteenth-century edition, that published by Ticknor and Fields, with the wood-engraving entitled Blind Man's Buff (see below).

Green is delineating a very non-denominational, secular, and upper-middle-class Christmas, as one notices from the abundant display of crystal glasses, silverware, furnishings, pictures on the wall, and, in particular, the fashionable clothing of the uncle, Fred, and his wife (whose name is never given). This might be the home of Charles and Catherine Dickens themselves at December 1836, their first Christmas as a married couple, when they lived at Furnival's Inn. Fred's wife is pregnant with the couple's first child, although the illustration does not reflect this point, other than to show her with her feet up on a cushion; Charles Dickens, Jr., was born 6 January 1837, so that a family entertainment on this scale probably did not occur at Furnival's that Christmas. The ebullient Topper, prominent in these scenes at Fred's, might well be the young John Forster, whom Dickens met at Christmas 1836, the writer who would see many a Dickens novel, including Oliver Twist, through the press and would eventually write the celebrated Dickens biography.

Relevant Images from other editions, 1843-1878

Left: Leech's tailpiece for the final stave showing Scrooge's entertaining his clerk in his own home, Scrooge and Bob Cratchit, or, The Christmas Bowl. Right: Eytinge's interpretation of what Scrooge saw at Fred's in his dream vision, Blind Man's Buff (1868).

Above: E. A. Abbey's realisation of the same scene at nephew Fred's, "It's I. Your Uncle Scrooge! I have come to dinner. Will you let me in, Fred?" (1876).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

____. A Christmas Carol. With 27 illustrations by Charles Green, R. I. Pears' Christmas Annual. London: A & F Pears, 1892.

____. A Christmas Carol. With 31 illustrations by Charles Green, R. I. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Created 31 August 2015

Last modified 14 March 2020