Introduction: work and reputation

Paul Mary Gray is one of many illustrators of the mid-nineteenth century whose work has slipped into obscurity. Versatile and able to respond to diverse texts, he published illustrations in some of the leading periodicals of the 1860s, notably Once a Week, The Sunday Magazine and Good Words, as well as contributing to the gift-books, A Round of Days and what is now the rarest of its genre, Idyllic Pictures (1866–67). Though only living to the age of 24, Gray established himself as an artist of repute and was widely praised by Victorian and later observers. The Dalziels (1901) speak highly of his sensitivity, noting in their Record his ‘fine feeling for black and white’ (p.307); Gleeson White (1897) is similarly enthusiastic (p.157), and Simon Houfe (1978, 1996) describes him as an accomplished designer, whose ‘gentle pastoral studies’ are among the finest of their time (p.157). Only Reid (1928) is disparaging, and ‘cannot help thinking’ that Gray’s ‘importance has been exaggerated’ (p.262), and it is surprising to find he does not feature at all in Goldman’s Victorian Illustration (1996, 2004), the standard modern account of the period. What all critics acknowledge is the quality of his work bearing in mind the shortness of his life. As the Dalziels remark, his contribution is essentially one of ‘considerable promise’ cut short (p.307).

Gray was mourned by those in the business of illustration, and his reputation in the twentieth century was protected by critics and collectors such as Harold Hartley. Hartley preserved more than two hundred of Gray’s drawings and proofs in his vast archive, which he donated in 1955 to The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These works have never been investigated in detail, and in modern scholarship the art of this interesting designer is otherwise relegated to the footnotes. His life and achievement are recovered here.

‘That clever young artist’: life and art

Paul Gray was an Irish Catholic; born in Dublin on 17 May 1842, he moved to London in 1863 and died in Brighton on 14 November 1866. His background was middle-class; though Catholic rather than Protestant in a period when Ireland was controlled by an Anglo-Irish Protestant elite, he was relatively privileged and was not immediately pressed to earn a living. His father was the proprietor of a musical academy in Dublin and Gray was educated at the St. Stanislaus Jesuits’ school, a boarding institution for Catholic boys in Tullabeg, Rahan, County Offaly. The convent prepared its students for university and to enter the priesthood, and on leaving he became for a short while a novitiate at Woodchester Priory in Stroud, Gloucestershire, a Dominican house set up in 1853 and one of the first of the re-established monastic houses in England. This proved a false turn: as Strickland remarks, he found he ‘had no vocation’ for the religious life and returned to Dublin, where he pursued a career in art.

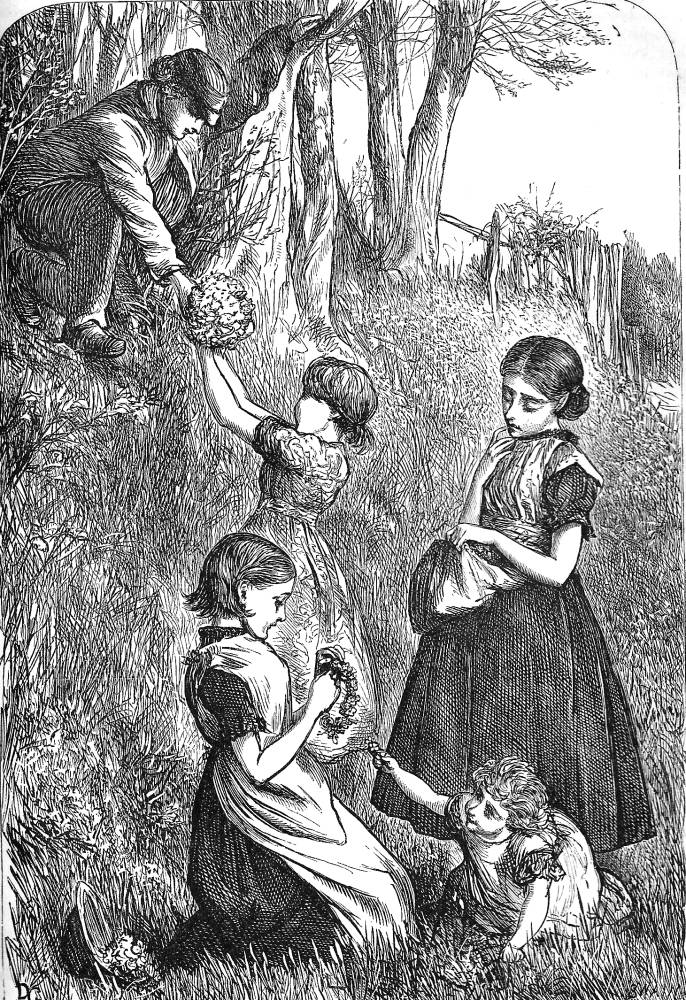

Left: Among the Flowers by Paul Gray. Right: The Gang Children by George John Pinwell (1842–75). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The nature of Gray’s training is unknown and like many illustrators of the period – such as M.E. Edwards and Charles Bennett – he was largely self-taught. He does not appear to have attended art-school, although the prosperity of his background probably meant he was coached at home by a teacher. Equipped with a ‘marked’ talent for art, even if he had little formal training, he found employment with a Dublin print-seller and for a while returned to Tullabeg, where he worked as a drawing master. He also exhibited a number of paintings at The Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin (1860–63).

Yet opportunities were limited in his native Ireland. His move to London was motivated by sensible economic considerations; following in the footsteps of Irish (Protestant) artists such as John Franklin and Daniel Maclise, he aimed to gain access to the vast art-markets of the capital, where he sought to establish himself as a painter in oil and watercolour. In practice, though, he did little but immerse himself in what was already a hyper-competitive nexus where supply for painted images entirely outstripped the demand, and only the most distinguished could hope to support themselves on earnings from the sales-rooms and private commissions. This was never a success. He managed to produce some paintings, exhibiting three figure-subjects in 1867 at The Royal Academy, but was otherwise without employment. To survive he turned to drawing on wood, providing illustrations for periodicals such as Once a Week, The Quiver and Samuel Lucas’s Shilling Magazine, as well as Punch, Fun and The Savage Club Papers. In this sense he again pursued a well-trodden track: John Franklin, E. H. Wehnert, A. W. Bayes, A. B. Houghton were all primarily fine artists who turned to the book-trade to make a living, and Gray was yet another in a large ensemble of jobbing designers who competed for work by lobbying the engravers and presenting their portfolios at the publishers’ offices.

That this inexperienced artist made his mark in so short a time is in one sense a reflection of his talent and – more importantly – the publishers’ recognition of his utility. His particular strength was his combination of versatility and distinctiveness. He designed a few witty cartoons for Punch and Fun and dramatic imagery for Charles Kingsley’s Hereward the Wake in Good Words (1865); but he was especially adept at pastoral scenes of lovers, mothers and children, practising the ‘poetic realism’ (Reid, p.2) of the style known as The Sixties.

Producing quality work was the mainstay and like all his contemporaries he was deeply engaged with the practicalities of business. A few surviving traces of his working arrangements suggest he was a conscientious practitioner and perhaps a shrewd one. The Dalziels report his close scrutiny of the proofs and his approval of their cutting, which ‘could not possibly be better’ (p.307). Always self-congratulatory, the Dalziels fail to register the fact that a young artist aiming to establish himself is unlikely to be critical in the fashion of Dante Rossetti and Fred Sandys, and probably praised their work in order to gain further employment; like every vulnerable freelance, he knew how to flatter his employers. Getting regular payment for work turned over so quickly was a constant worry for artists of his generation, and Gray was entirely unexceptional in his efforts to be rewarded punctually and at the appropriate level. This was not always an easy task in an economic framework in which there were no contracts, and publishers and editors could pay whatever they liked. But there is also surviving evidence of more pragmatic dealings with the hard-headed Samuel Lucas, the editor of Once a Week and the proprietor of the what is now the rarest periodical of its type,The Shilling Magazine. Receipts and letters between Lucas and Gray (1866–68) reveal that he was paid just six guineas for one unspecified illustration in The Shilling Magazine – an amount to the lower end of the pay-scale when £10 or 10 guineas was the likelier sum. Gray’s miserly £6 and 6 shillings suggests that at the end of his short life he was still very much in the process of establishing himself, and could only command the minimum remuneration; tellingly, he died intestate and had no property.

Gray’s dying of tuberculosis brought an unexpected close to a promising career. Indeed, he was one of a golden generation that never reached old age: Fred Walker, A. B. Houghton, George Pinwell, E. H.Wehnert and the suicide Thomas Morten were all part of this grim tally. And as with all of these practitioners the pressure of work was a contributory factor in his decline; Strickland claims he was ‘never strong’, his health collapsing ‘under the incessant strain of his work’; in the words of the Dalziels, he was always ‘delicate’ (p.307).

Andrew Halliday, the editor of The Savage Club Papers, left a memorial in his preface for the edition of 1867, which contains Gray’s final design. Halliday is sentimental and unctuous while suggesting some other, unconsidered dimensions to the artist’s life:

The last words which I have to utter in this place are burdened with a sadness which scarcely leaves me the power of expression … He lived just long enough to finish his drawing; - and then left us, to join the friend whom he loved in that land where there is no parting, and where tears are dried for ever … [p. xiv].

Halliday’s encomium for this ‘clever young artist’ suggests the esteem in which he was held, but references to the death of the ‘dear friend’ whom ‘he loved’ and whose demise was a fatal blow, are tantalising. References to Gray as ‘a gentle spirit’ (p.xiv) and his love for a companion not specified as a woman may be a coded way of recognising his homosexuality at a time when men of the ‘Greek persuasion’ were criminalised.

Gray was certainly unusual in being an Irish Catholic artist among practitioners who were members of the Protestant Ascendancy. He was buried in the St Mary’s Catholic Cemetery adjacent to Kensal Green Cemetery, London. His friends erected a large and imposing monument in the form of an austere cross, which still survives.

Gray as an illustrator

Gray’s presence among the outstanding illustrators of the period is often noted, but there is currently no analysis of his style. Some of his work was driven by the need to provide efficient illustrations for sentimental poetry, and many of these images are relatively undistinguished. He produced the usual quota of death-bed scenes and parting lovers which are mainly conventional. However, he found his own voice in servicing what appear to be absolute opposites: pastoralism and intense psychological drama. He is his most inventive and distinctive when he turns to these types of work, creating images which are by turns lyrical and unsettling.

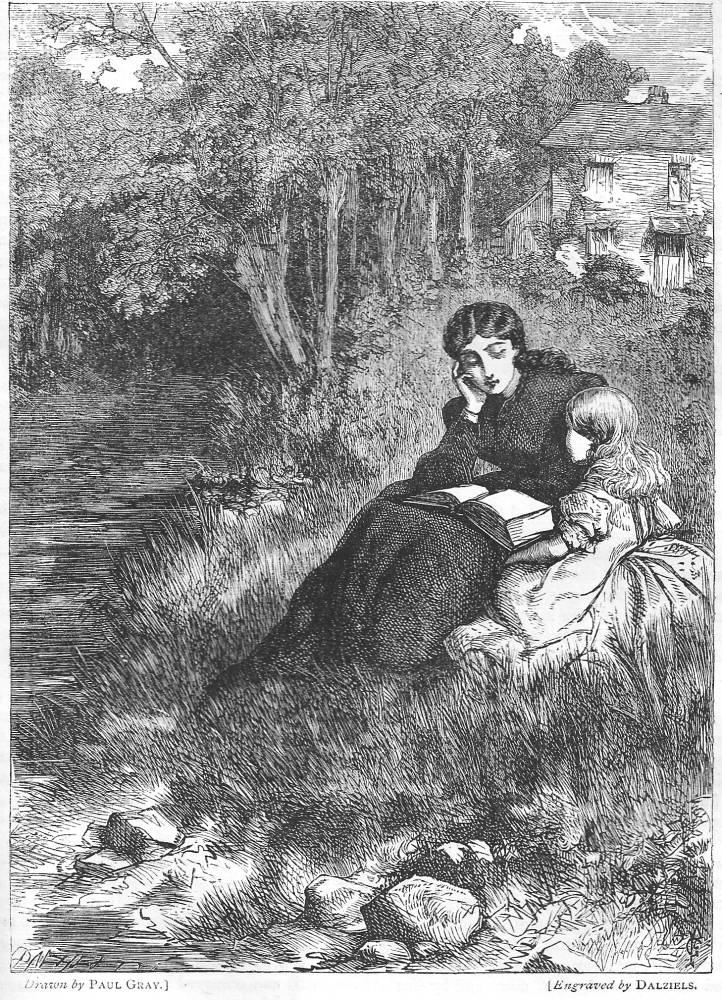

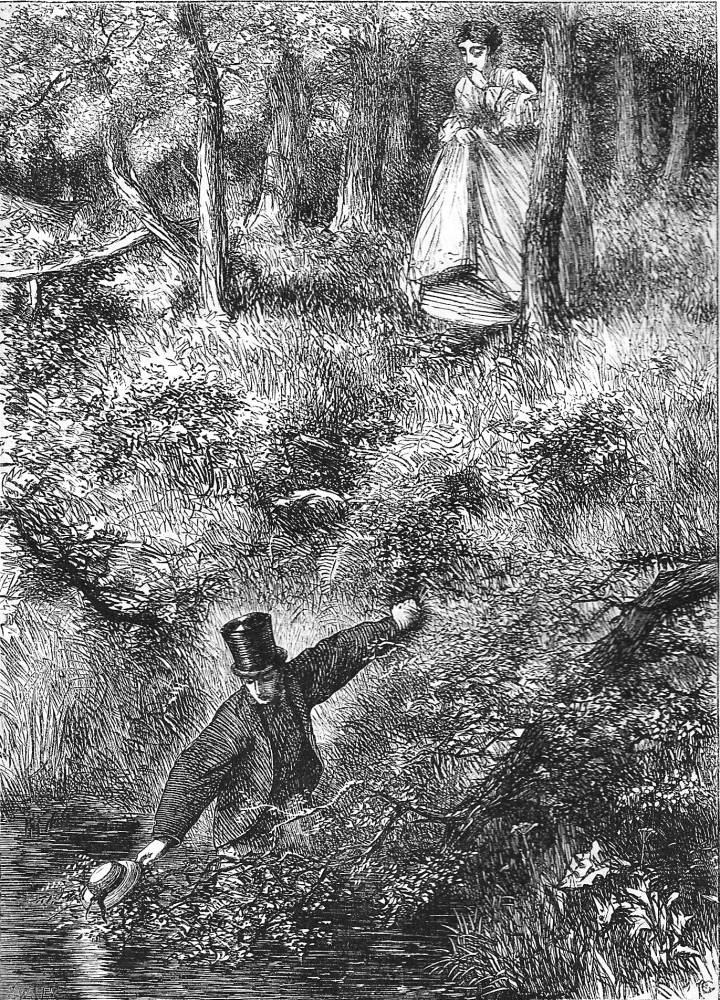

Left: Katie wanders by the stream. Right: Cousin Lucy. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Though never categorised in these terms, Gray made a significant contribution to the sub-genre of Sixties design which Reid labels ‘The Idyllic School’ (p.134). His illustrations, like those of Fred Walker and J. W. North, are explorations of a version of country life which is unaffected by industrialisation and celebrates a Romantic notion of English landscape. These images convey the wildness and mystery of the rural, and it could be that he applies his perceptions of the relatively uncultivated Irish landscape to the suburban neatness of England, transforming it into a dreamy idyll and infusing its spaces with a sense of mystery. He particularly focuses on the disjuncture between Nature and Civilization, as embodied in the form of middle-class visitors. In Katie wanders by the stream (The Quiver, 1866, p.505) he shows a girl tentatively inspecting the water, her skirt pulled up to reveal tiny, toy-like feet which form a delicate contrast with the luxuriance of the trees and foliage. Likewise in Cousin Lucy (The Quiver, 1866, p.681), he presents a studied opposition between the absorbed face of the heroine and the ‘little house by the riverside’ (p.683) and its framing trees.

These images convey a strong sense of nature observed which links to the everyday realism of North and George Pinwell; however, Gray was not interested in social observation in the manner of these artists and is only concerned with celebration of the pastoral. Among the Flowers (The Sunday Magazine, 1866, facing p.624) is a good example of this lyricism. The poem, ‘by a curate’, has a social message in its narrative of slum-children finding redemption in the beauty of nature, but Gray transforms it into a moment of simple wonder and delight as the children gather the flowers. As so happens in the Anglican magazines of the period, the artist finds a genuinely uplifting message to countermand the piety of the text.

These intense and moving illustrations confirm the Dalziels’ claim that Gray was a sensitive artist (p.307) with a strong capacity to convey emotion through understatement and the workings of the pathetic fallacy. He seems on the other hand to have appreciated the need to find a visual style that would register high drama and strange states of mind, and the two branches of his art, lyrical and psychological, seem strangely unrelated, barely the work of one hand.

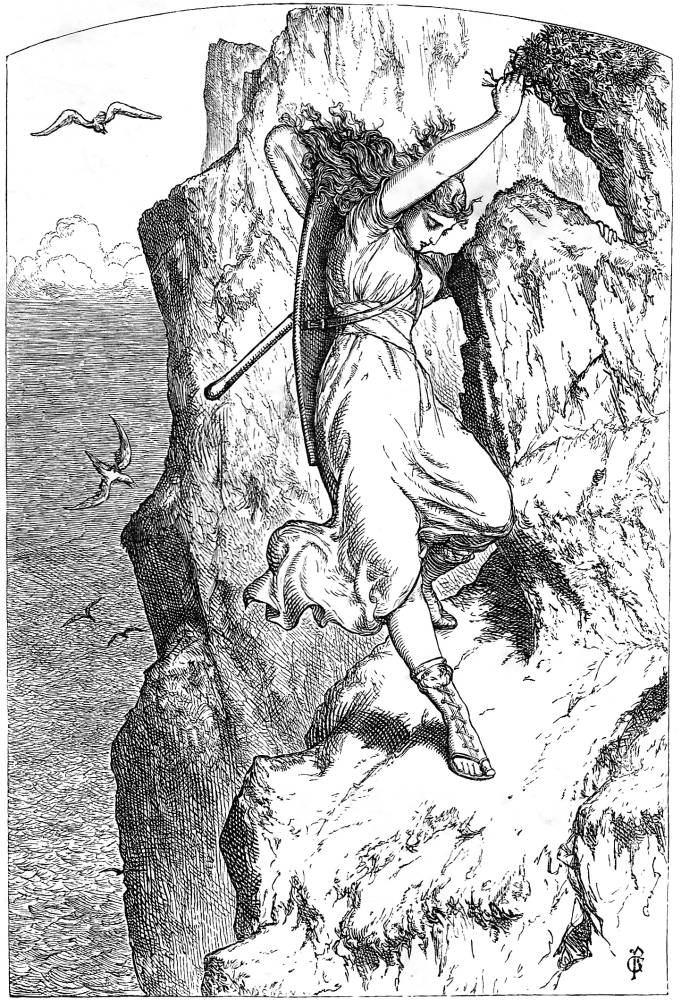

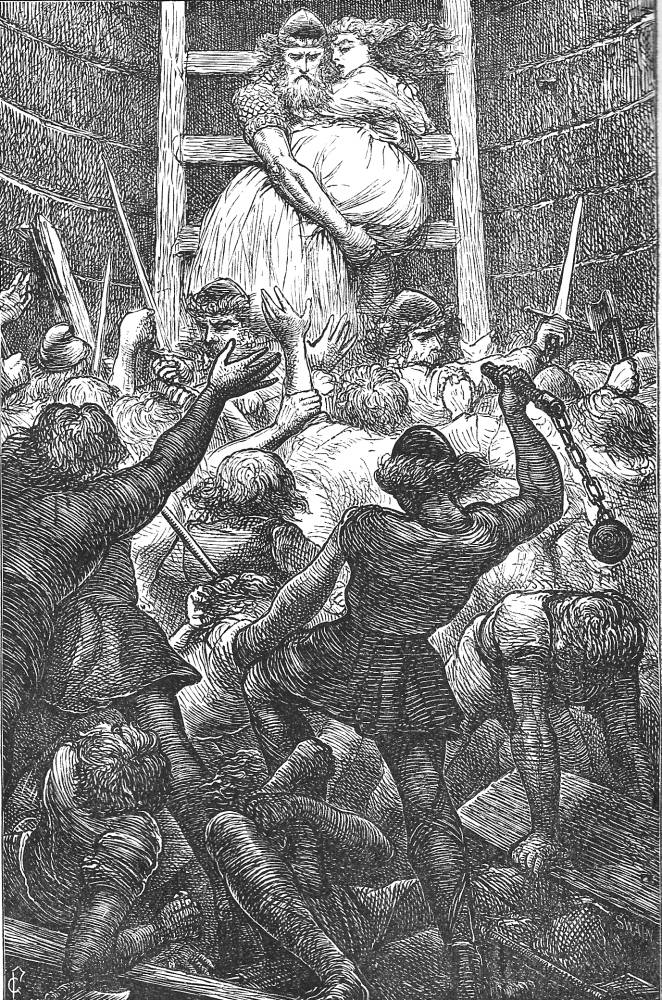

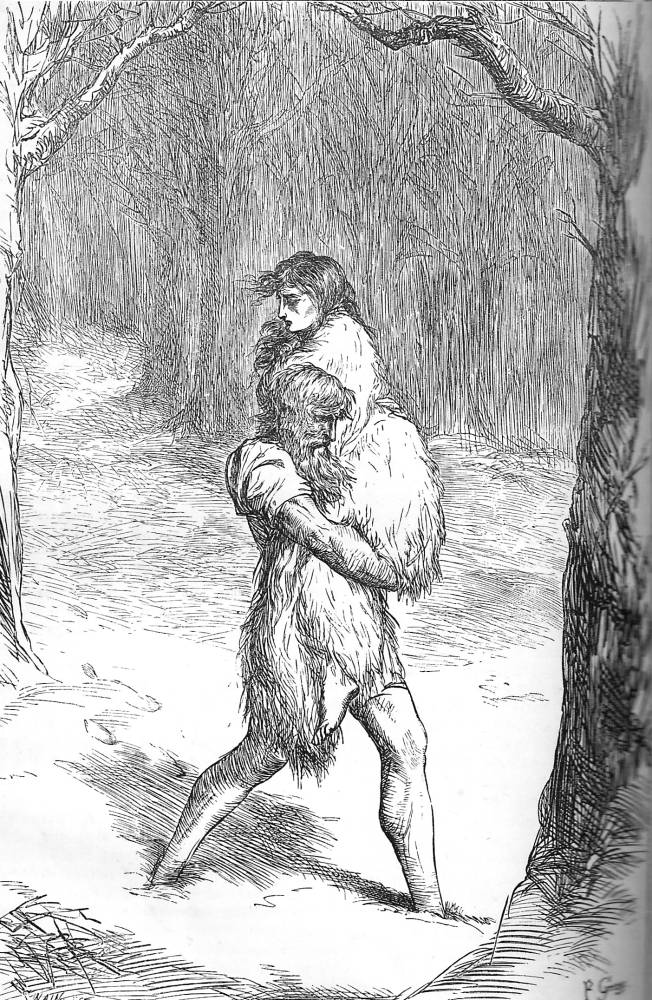

Left: The Huntress of Armorica. Middle left: He caught her in his arms. Middle right: Martin hurried on. Right: illustration for ‘Quid Femina Possit.’ [Click on images to enlarge them.]

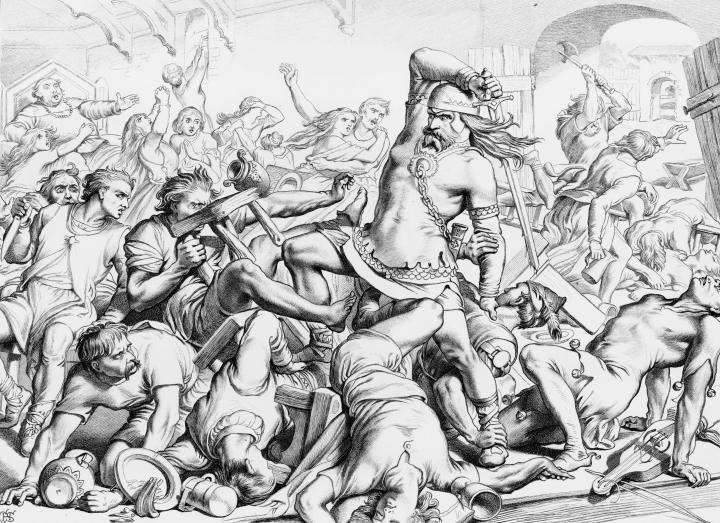

His most sustained work in the dramatic idiom is his series for Charles Kingsley’s Hereward the Wake, which appeared in Good Words in 1865. Gray’s approach to this material is what in conventional terms might be called ‘atmospheric’, figuring the author’s dramatic personae in a montage of dense tableaux which stress the fiction’s emotional extremes and heighten its effects by using chiaroscuro and expressive distortion. In place of the sweet lyricism of pastoral scenes we have instead a series of dream-like settings in which the characters compete for space or, in complete reverse, seem to be dislocated from each other. And then began a murder, grim and great (facing p. 143) is the most extreme composition: the upraised sword is elongated to accentuate its deadly sharpness and the clasped hands are dramatically enlarged and distorted; all around are bodies in a tumult of disorder which is described by overlapping diagonals. Similarly powerful is He caught her in his arms (f.p.413), this time shifting the axis to the vertical; the outlines of the ladder down form a calculated contrast to the dynamic outlines of the struggling figures below and the effect is again one of nightmarish dislocation and strangeness.

Left: And then began a murder, grim and grea by Paul Gray. Right: Hereward clearing Bourne of Frenchmen by Henry Courtney Selous (1803-90). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In adopting this approach Gray significantly alters the focus of Kingsley’s tale, emphasising its violence and cruelty rather than its heroism. It forms an interesting contrast with H. C. Selous’s version of 1870, which figures the action as a celebration of Imperial machismo (Cooke, ‘Interpreting Masculinity’, pp. 128–29). More especially, it reveals Gray as an experimental artist, who stretches the limits of mid-Victorian realism; though not entirely unique, his treatment of Kingsley’s text is one of the few examples of the style of ‘The Sixties’ put to the service of a fiction to which it is not obviously well-matched. Gray, though, finds an accommodation – managing to combine the idiom’s academic exactitude with the suggestive workings of distorted limbs and facial expressions.

His capacity to represent suffering is notably developed in his portraiture. The characters in Hereward are carefully identified by their faces, and Gray develops this emphasis in his treatment of the sick-room. Most touching is She will never carry roses more (The Quiver, 1866, p.1). This is a variant on a well-established type, but the artist adds a note of genuine tragedy in the treatment of what is supposed to be a representation of cholera but looks more like consumption, perhaps in recognition of his own experience of the illness. The contrast between the sufferer’s wasted visage and the unseen face of the nurse adds to the drama, and Gray deploys a matter of fact realism to give the scene a sharp actuality.

Gray might thus be described as an interesting artist who was able to evoke strong emotion, and had a considerable range. His willingness to work within a conventional idiom and stretch its possibilities is an indication, perhaps, of his youthfulness and lack of training. As noted earlier, some of his designs are purely ordinary, the rank and file of the period; yet at his best he displays both inventiveness and originality. It is impossible to know what Gray might have achieved had he lived longer. What remains is a small but significant contribution to the graphic art of the period.

Works Cited and Sources of Information

The Brothers Dalziel. A Record of Work, 1840–1890. 1901; reprint, with a Foreword by Graham Reynolds. London: Batsford, 1978.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. Pinner: PLA; London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Cooke, Simon. ‘Interpreting Masculinity: Pre-Raphaelite Illustration and the Works of Tennyson, Christina Rossetti and Trollope’. Pre-Raphaelite Masculinities. Eds. Amelia Yeates and Serena Trowbridge. Burlington, VT: 2014. 127–150.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; rev. ed., Lund Humphries, 2004.

Good Words. London: Strahan, 1865.

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth Century British Book Illustrators. Woodbridge: The Antique Collectors’ Club, 1978; revd ed., 1996.

Idyllic Pictures. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1867.

London Society. London: Clowes & Co., 1866.

Once a Week. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1864–1866.

Paul Gray correspondence in a private collection.

The Quiver. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1867.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; New York: Dover, 1975.

A Round of Days. London: Routledge, 1866.

The Savage Club Papers. Ed. Andrew Halliday. London: Tinsley, 1867.

Selous, H. C. Illustrations to Hereward the Wake by Charles Kingsley. London: Art Union, 1870 [1869].

The Shilling Magazine. London: Boswell, 1866.

Strickland, Walter. A Dictionary of Irish Artists. 1913; online version. www.libraryireland.com/irishartists/paul-mary-gray

The Sunday Magazine. London: Strahan, 1866.

White, Gleeson. English Illustration: The Sixties, 1855–70. 1897; rpt. Bath: Kingsmead, 1970.

Created 18 February 2015