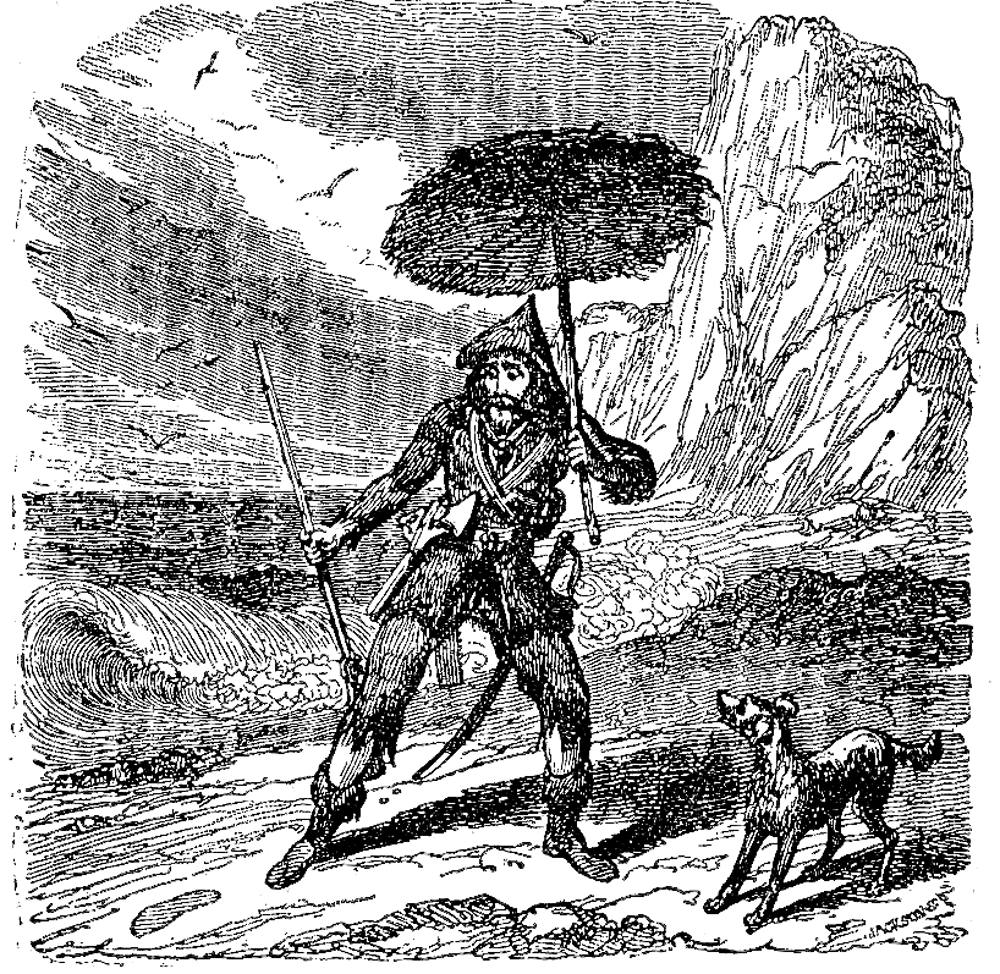

Robinson Crusoe discovers a Foot-print

Sir John Gilbert, R. A.

1867?

Wood-engraving

7.6 cm high x 5.4 cm, vignetted

Illustration for Daniel Defoe's Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Daniel Defoe —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Sir John Gilbert, R. A. —> Next]

Robinson Crusoe discovers a Foot-print

Sir John Gilbert, R. A.

1867?

Wood-engraving

7.6 cm high x 5.4 cm, vignetted

Illustration for Daniel Defoe's Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

But now I come to a new scene of my life.

It happened one day about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man’s naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen on the sand. I stood like one thunderstruck, or as if I had seen an apparition. I listened, I looked round me, but I could hear nothing, nor see anything; I went up to a rising ground to look farther; I went up the shore and down the shore, but it was all one; I could see no other impression but that one. I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my fancy; but there was no room for that, for there was exactly the print of a foot — toes, heel, and every part of a foot. How it came thither I knew not, nor could I in the least imagine; but after innumerable fluttering thoughts, like a man perfectly confused and out of myself, I came home to my fortification, not feeling, as we say, the ground I went on, but terrified to the last degree, looking behind me at every two or three steps, mistaking every bush and tree, and fancying every stump at a distance to be a man. Nor is it possible to describe how many various shapes my affrighted imagination represented things to me in, how many wild ideas were found every moment in my fancy, and what strange, unaccountable whimsies came into my thoughts by the way. [Chapter XI, "Finds the print of a man's foot on the sand"]

The illustration commemorates — even for readers unfamiliar with the actual text of the story — the most significant event in the plot in that the discovery of the footprint (not necessarily the footprint of Friday, despite the captions in some narrative-pictorial series) signals a huge shift in the action from Crusoe as survivalist to Crusoe as master and, once again as with Xury in the Sallee adventure, a social being. Robert L. Patten has described Cruikshank's treatment of this incident cogently, pointing out how it rather than Stothard's earlier visualisation has set the standard for later illustrators:

When Crusoe and his dog discover Friday's footprint (a must for any illustrator), Stothard's hero muses, while Cruikshank's starts back amazed, apprehensive, hopeful, "like one thunderstruck,"as the text insists (fig. 68). Every line of Crusoe's body mimes a startled nervous reflex, his umbrella makes a grotesque exclamation point, and his dog draws back, front legs stiff, head turned to his master, ear roots tensed, tail arrested. Cruikshank picks moments of travail and resourcefulness. And he designs his cuts to be dropped into the text, where they play with and against the surrounding letterpress to bring out the medley of tones inherent in the narrative. [pp. 336-337]

By 1867, Sir John Gilbert had several models to draw upon, for he probably saw and studied both the Stothard plate, first printed in 1790, and Cruikshank's response in which the islander is not merely puzzled, but shocked, startled, and amazed at such a discovery after so many years alone. The vignette gives us just a glimpse in the background of this tropical island at the mouth of the Orinoco River, opposite what is now the Venezuelan coast, although it was in those days merely "The Brazils." Gilbert in this simple line drawing probably hoped to communicate far subtler emotions passing across the visage of the solitary colonist, but the scale of the vignette simnply does not provide for such a nuanced response to the great discovery.

Left: Stothard's study of a man puzzled rather than startled as Crusoe accompanied by his dogfinds a footprint near the roaring breakers: Robinson Crusoe discovers the print of a man's foot (Chapter XI, "Finds the print of a man's foot on the sand." (copper-engraving). Right: Cruikshank's wood-engraving of this highly charged moment, Friday's Footprint — Crusoe discovers a human footprint on the beach (1831).

Left: The colourful children's book's depiction of Crusoe's stunning

discovery,

De Foe, Daniel. The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Written by Himself. Illustrated by Gilbert, Cruikshank, and Brown. London: Darton and Hodge, 1867?].

Patten, Robert L. "Phase 2: "'The Finest Things, Next to Rembrandt's,' 1720–1835." Chapter 20, "Thumbnail Designs." George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, vol. 1: 1792-1835. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers U. P., 1992; London: The Lutterworth Press, 1992. Pp. 325-339.

Last modified 19 February 2018