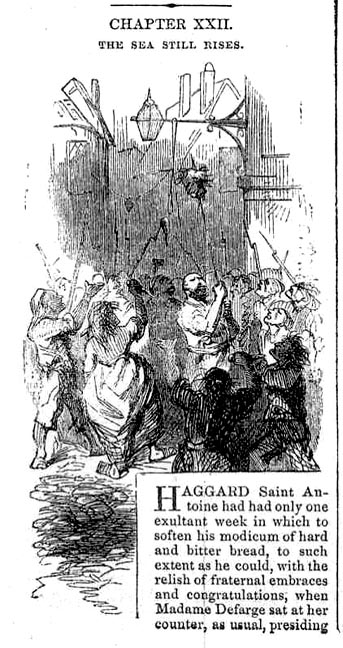

The End of Foulon by Harry Furniss. 1910. Framed lithograph, 9.4 x 14.4 cm. Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing XIII, 217. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

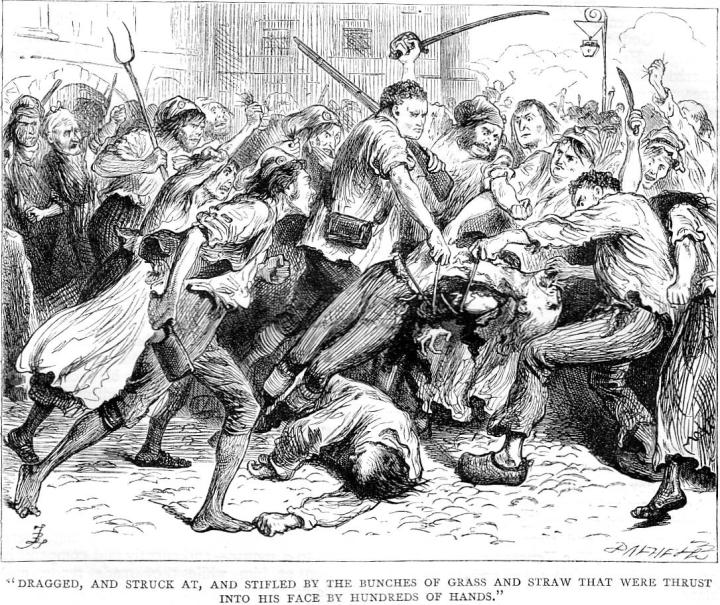

Down, and up, and head foremost on the steps of the building; now, on his knees; now, on his feet; now, on his back; dragged, and struck at, and stifled by the bunches of grass and straw that were thrust into his face by hundreds of hands; torn, bruised, panting, bleeding, yet always entreating and beseeching for mercy; now full of vehement agony of action, with a small clear space about him as the people drew one another back that they might see; now, a log of dead wood drawn through a forest of legs; he was hauled to the nearest street corner where one of the fatal lamps swung, and there Madame Defarge let him go — as a cat might have done to a mouse — and silently and composedly looked at him while they made ready, and while he besought her: the women passionately screeching at him all the time, and the men sternly calling out to have him killed with grass in his mouth. Once, he went aloft, and the rope broke, and they caught him shrieking; twice, he went aloft, and the rope broke, and they caught him shrieking; then, the rope was merciful, and held him, and his head was soon upon a pike, with grass enough in the mouth for all Saint Antoine to dance at the sight of. [Book Two, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "The Sea Still Rises," 212: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

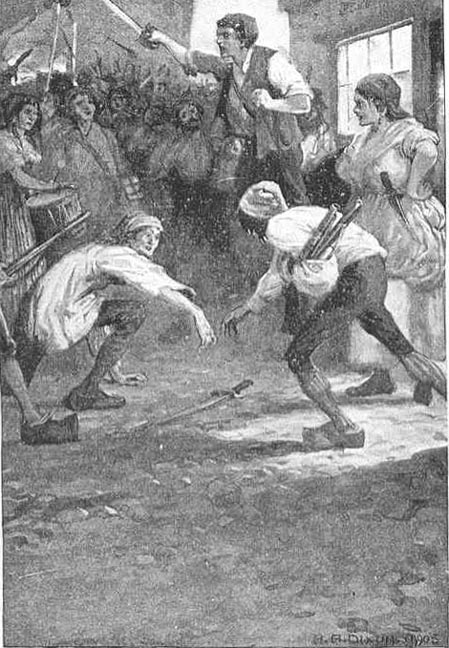

Whereas the novel's first American illustrator, John McLenan, reinforces the violence of the outbreak of the Revolution through the wood-engraving within Chapter 21 for the 3 September 1859 instalment entitled "In the name of all the angels or devils, work!", and a gruesome headnote vignette (see below) for the following week's instalment (10 September), in which the revolutionary mob hangs Foulon de Doué, the Controller-General of Finances, from a lamp-standard near the Hôtel de Ville in the twenty-second chapter, Phiz in one of his two monthly illustrations for October 1859 focuses on the swirling action of the mob itself just prior to the destruction of a uniformed Foulon at the City Hall of Paris. Although he includes the lamp-standard upon which the heartless functionary of the Old Regime is about to be hanged, Fred Barnard in the Household Edition wood-engraving that parallels Phiz's steel-engraving eliminates the Vengeance and Madame Defarge, but places the hapless victim of the mob's outrage and the muscular Ernest Defarge at the centre of the chaotic composition entitled Dragged, and struck at, and stifled by the bunches of grass and straw that were thrust into his face by hundreds of hands (see below), the scene set outside the Hôtel de Ville in Chapter Twenty-two, "The Sea Still Rises," in Book Two).

Thirty-five years after Barnard's illustration and fifty years after Phiz's, Furniss, apparently having studied both of these illustrations of the scene of mob violence, synthesizes the earlier illustrations in his lithograph, moving a cartoon-like Foulon to the right, but enlarging his figure considerably, and indicating to the left of centre the handful of hay that a zealous Jacobin (as denoted by his Phrygian cap) will presently cram down the bureaucrat's throat. On the other hand, only eight years after the original serial publication, the other sanctioned Dickens illustrator, Sol Eytinge, Jr., focussed on the ghoulish leader of the ragged insurgents, The Vengeance, in his depiction of the outbreak of the Revolution in the streets of the faubourg Saint Antoine, and offered no architectural context or informing cityscape, but only a sea of angry faces. A. A. Dixon in his 1905 lithograph identifies the Saint Antoine wine-shop as ground zero for the revolution, but only suggests the ensuing violence by having the Defarges hand out purloined sabres to the mob. Whereas both Phiz and Barnard offer some contextual elements such as the towers of the Bastille on the skyline to establish the setting (in front of the Hôtel de Ville, about two miles from the prison-fortress, and therefore within easy walking distance of the suburb of Saint Antoine), Furniss like Eytinge has elected not to offer such clues and to focus instead upon the faces in the mob.

In the turbulent lithograph from an ink-and-wash drawing Furniss focuses upon the Phrygian caps that, as Sanders notes, "became both an emblem of the Revolution and a common item of dress amongst sansculottes" (121). Sanders further notes that Dickens's account of the death of Foulon at the hands of the Defarges and their Saint Antoine compatriots "is substantially from Carlyle" (FR 1.3.9 and 1.5.9), as on the 22nd of July, a week after the fall of the Bastille (which is being demolished on the skyline in Phiz's illustration), the financier who had hastily remarked that "The people may eat grass" now faces the wrath of the many-headed hydra:

With wild yells, Sansculottism clutches him, in its hundred hands: he is whirled across the Place de Grève, to the 'Lanterne', Lamp-iron which there is at the corner of the Rue de la Vannerie; pleading bitterly for life, — to the deaf winds. Only with the third rope (for two ropes broke, and the quavering voice [of Foulon] still pleaded,) can he be so much as got hanged! His Body is dragged through the streets; his Head goes aloft on a pike, the mouth filled with grass: amid sounds as of Tophet, from a grass-eating people. (1.5.9) [as cited by Sanders, 122]

Although the figures are generalised sans culottes in the main (except for the uniformed Foulon himself), Furniss has inserted to the extreme the drum-beating Vengeance, who is also recognisable in Furniss's previous illustration, The Fall of the Bastille. Foulon looks shocked as he realizes that the Jacobin in the left foreground intends to stuff his mouth with straw, but at least four other members of the mob are clutching fistfuls of straw. Like Phiz and Barnard, Furniss depicts Foulon caught up by the mob and buffeted, but not yet hanged and beheaded. Although the mob are pointing towards the right, Furniss has not indicated where the surging sea of humanity is drifting, namely towards a lamp standard, as described in the accompanying text. Whereas Furniss has made Foulon's torso a vertical and has rendered his thighs on a right-to-left diagonal, the crowd is overwhelmingly aligned on an opposing, left-to-right diagonal, so that the lone victim seems to be fruitlessly resisting the tidal movement from left to right, from past to future, and from repression to freedom.

The male and female figures (centre) immediately to the left of the ensnared and embattled Foulon may be the Defarges, although these figures do not resemble the publicans of the earlier scenes, Defarge and Knitting. Whereas the women appear to be the leaders of the mob in Dickens's text, and are accorded prominence in Phiz's October 1859 illustration, The Sea Rises (see below), Furniss's post-Bastille Saint Antoine mob is overwhelmingly male. More significant than the issue of gender is the impression that Furniss conveys through this vigorous, insistent mass of downtrodden humanity on the move, now unstoppable and inexorable, and of one mind, so that the very composition of the scene underscores the inevitability of the destruction of Foulon and all of his ilk who in serving the establishment served themselves rather than the people of France.

Consideration of the issues underlying the French Revolution, prompted by examining Furniss's wash drawings The Fall of the Bastille and The End of Foulon (unlike Phiz's somewhat allegorical The Sea Rises, titles suggestive of their chronicling historical events) prompts one to consider Furniss's sources of inspiration, for his style of illustration here is so markedly different from the line drawings that dominate the first half of the book. On the one hand, as the captions beneath these historically-based dark plates suggest, Furniss is realising scenes in the Dickens text. However, the general absence of specific characters from A Tale of Two Cities and the antecedents in Thomas Carlyle's The French Revolution both suggest that, aside from his usual extra-textual sources, the illustrations of Hablot Knight Browne and Barnard, Furniss has consulted Carlyle and other historical commentaries. In this illustration, we have both history (the destruction of a noteworthy member of the ancien régime on a particular day and at a particular place) and literature, as the presence of The Vengeance suggests. The shift in style, then, from line drawings realizing characters in the text to wash drawings reproduced lithographically, surely signals some intention on Furniss's part to convey impressionistically the sheer power of actual events in the Revolution, as well as their influence on the history of Europe over the nineteenth century. Taking this century-long perspective, Furniss would have us realise that, whereas we view literary characters and events directly and have sufficient authorial comment to assess them accurately, we view the reportage of history in a fragmented and flawed manner, subject to omissions and biases, through a glass darkly. The result of this shift in style is not nearly so satisfying to the viewer as Phiz's detailism and Barnard's realism.

Furniss's Six Other Darkened Lithographs for Historical Moments in the Novel

- 3. Stopping the Dover Coach, Book the First, "Recalled to Life," Chapter Two, "The Mail," facing 8.

- 21. The Fall of the Bastille, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "Echoing Footsteps," facing 201.

- 23. On the Way to Paris, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread, "Chapter One, "On the Road to Paris," facing 232.

- 25. The Grindstone, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 2, "The Grindstone," facing 256.

- 26. The Carmagnole, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 5, "The Wood-Sawyer," facing 265.

- 31. Sydney Carton and the little Seamstress, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 13,"Fifty-Two," facing 337.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions: 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905.

Left: John McLenan's main illustration for Book 2, Chapter 22, Headnote vignette of the "Wolf-procession through the streets" for Chapter XXII. The Sea Still Rises. Right: Phiz's "The Sea Rises" (October 1859).

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the grotesque mob-leader as the virago leads Saint Antoine against the defenders of the fortress, "The Vengeance" (1867). Centre: Fred Barnard's "Dragged, and struck at, and stifled by the bunches of grass and straw that were thrust into his face by hundreds of hands" (1874); right: A. A. Dixon's closeup of the Saint Antoine mob gathering outside the Defarges' wine-shop, "Patriots and friends, we are ready" for Book Two, Chapter 21, "Echoing Footsteps" (1905).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Mengel, Ewald. "The Poisoned Fountain: Dickens's Use of a Traditional Symbol in A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian, 80/1 (Spring 1984): 26-32.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Created 12 December 2013

Last modified 11 January 2020