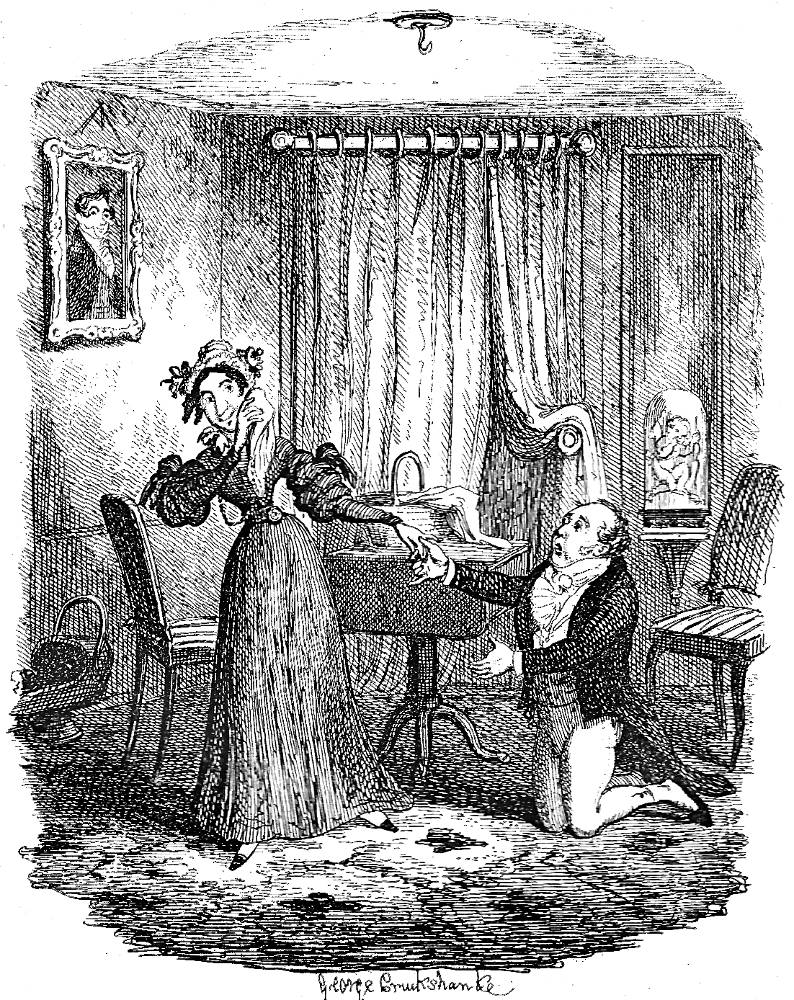

"And, as Fanny and the girl replaced the deal chimney-board," wood engraving by A. B. Frost for Part IV, "Tales": Chapter X, "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" — twenty-eighth illustration for Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People, page 258. 4 ⅛ by 5¼ inches (10.5 cm high by 13.2 cm wide), framed. To avoid a premature encounter with his bride Fanny's father, Gabriel Parsons has to resort to hiding in the kitchen fire-place on his wedding day until he and "the old boy" (his father-in-law) have reached an understanding.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliographical Information

The 1876 and 1877 British and American Household Editions of Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain a total of four illustrations for "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," two by Fred Barnard and two by A. B. Frost. This somewhat rambling narrative first appeared in the Monthly Magazine for January and February 1835, and became in 1839 the tenth chapter in "Tales." George Cruikshank provided three copper-plate engravings as illustrations for the lengthy story in the 1839 Chapman and Hall edition. Sol Eytinge, Jr., provided a single illustration for the story in the 1867 Diamond Edition (Boston: Ticknor & Fields), and Harry Furniss added a lively character study of the Sheriff-Officer's Mercury in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition. The present illustration by A. B. Frost appears on p. 258 in the 1877 Harper and Brothers edition with the following descriptive headline: "Mr. Solomon Jacobs's" (p. 259).

Passage Illustrated: Deferring "the pleasures of a matrimonial life"

The old boy had been very cross all day, which made her feel still more lonely; and she was quite out of spirits. So, I put a good face on the matter, and laughed it off, and said we should enjoy the pleasures of a matrimonial life more by contrast; and, at length, poor Fanny brightened up a little. I stopped there, till about eleven o’clock, and, just as I was taking my leave for the fourteenth time, the girl came running down the stairs, without her shoes, in a great fright, to tell us that the old villain — Heaven forgive me for calling him so, for he is dead and gone now! — prompted I suppose by the prince of darkness, was coming down, to draw his own beer for supper — a thing he had not done before, for six months, to my certain knowledge; for the cask stood in that very back kitchen. If he discovered me there, explanation would have been out of the question; for he was so outrageously violent, when at all excited, that he never would have listened to me. There was only one thing to be done. The chimney was a very wide one; it had been originally built for an oven; went up perpendicularly for a few feet, and then shot backward and formed a sort of small cavern. My hopes and fortune — the means of our joint existence almost — were at stake. I scrambled in like a squirrel; coiled myself up in this recess; and, as Fanny and the girl replaced the deal chimney-board, I could see the light of the candle which my unconscious father-in-law carried in his hand. I heard him draw the beer; and I never heard beer run so slowly. He was just leaving the kitchen, and I was preparing to descend, when down came the infernal chimney-board with a tremendous crash. He stopped and put down the candle and the jug of beer on the dresser; he was a nervous old fellow, and any unexpected noise annoyed him. He coolly observed that the fire-place was never used, and sending the frightened servant into the next kitchen for a hammer and nails, actually nailed up the board, and locked the door on the outside. So, there was I, on my wedding-night, in the light kerseymere trousers, fancy waistcoat, and blue coat, that I had been married in in the morning, in a back-kitchen chimney, the bottom of which was nailed up, and the top of which had been formerly raised some fifteen feet, to prevent the smoke from annoying the neighbours. And there," added Mr. Gabriel Parsons, as he passed the bottle, "there I remained till half-past seven the next morning, when the housemaid’s sweetheart, who was a carpenter, unshelled me. The old dog had nailed me up so securely, that, to this very hour, I firmly believe that no one but a carpenter could ever have got me out." [Part IV, "Tales," Chapter X "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter the First, pp. 257-58]

Commentary: Another Early Dickens Farce

As The Dickens Index suggests, in the two-part short story "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" Dickens makes use of the ludicrous plot gambits of the early Victorian farce:

Comic account of an impoverished middle-aged bachelor's attempt, initiated and organized by his prosperous friend, Gabriel Parsons, to capture the affections of a prim, well-to-do spinster, Miss Lillerton. During the course of the story Tottle is arrested for theft [actually, debt] and taken to a sponging-house, from which he is rescued by Parsons. [p. 191]

Although numerous illustrators have realised various comic moments in the two-chapter farce, only the American illustrator has selected this moment from Gabriel Parson's extended flashback to Watkins Tottle which forms an induction to the main tale, which occurs in the second chapter. Perhaps Parsons intends the anecdote to cure Tottle of his curious repulsion/attraction towards marriage — "rather uncommon compound of strong uxorious inclinations, and an unparalleled degree of anti-connubial timidity" (253). The reader encounters Parsons; narration of his wedding-day ordeal on the same page as Frost's illustration, which has the virtue of clarifying for a modern reader what the deal chimney-piece looks like and how the kitchen maid puts it in place. Fanny's gesture implies that both the maid and her bridegroom should say nothing as she hears her father's footsteps on the stair. Thus, Frost complements Parsons' narrative since, stuffed inside the fireplace, he cannot hear his father-in-law's approach, and registers his presence only when, through a crack where the deal board meets the edge of the fireplace aperture, he sees the candle. The overturned kitchen chair, suggestive of haste and confusion, reinforces the apprehensions of the maid and Fanny.

The story as first published in the Monthly Magazine in two parts (January and February 1835) contained no illustrations. The affable Gabriel Parsons, to whom Tottle is massively indebted, hopes to persuade the fifty-year-old bachelor to court the wealthy heiress Miss Lillerton. Unfortunately for Tottle, when Parsons learns that Miss Lillerton has already accepted the marriage proposal of the Reverend Charles Timson, he abandons Tottle. A few weeks later, unable to pay his bills or even his rent, Tottle drowns himself in the Regent's Canal.

Initial and Subsequent Editions of "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle" (1835-1877)

Probably because the actual name of the monthly journal in which the story first appeared in the opening months of 1835 was rather a mouthful — The British Register of Literature, Science and Belles Letters, Londoners of the 1830s simply called it The Monthly Magazine. Under the editorship of Captain J. B. Holland the small-circulation periodical could not afford to pay its contributors. Nevertheless, over the first three years of Dickens's career as a writer the literary journal enabled him, presenting himself under the pseudonym "Boz," to place before the reading public nine of his longest sketches, beginning with "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" and concluding with "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle."

As Frederic G. Kitton notes, Cruikshank had to re-engrave this illustration for the Chapman and Hall serialisation, and the subsequent 1839 anthology:

During the following year (1837) Macrone published a Second Series of the "Sketches" in one volume, uniform in size and character with its predecessors, and containing ten etchings by Cruikshank; for the second edition of this extra volume two additional illustrations were done, viz., "The Last Cab-Driver" and "May-day in the Evening." It was at this time that Dickens repurchased from Macrone the entire copyright of the "Sketches," and arranged with Chapman & Hall for a complete edition, to be issued in shilling monthly parts, octavo size, the first number appearing in November of that year. The completed work contained all the Cruikshank plates (except that entitled The Free and Easy, which, for some unexplained reason, was cancelled) and the following [twelve] new subjects: "The Parish Engine," "The Broker's Man," "Our Next-door Neighbours" [sic], "Early Coaches," "Public Dinners," "The Gin-Shop," "Making a Night of It," "The Boarding-House," "The Tuggses at Ramsgate," "The Steam Excursion," "Mrs. Joseph Porter," and "Mr. Watkins Tottle." ["George Cruikshank, p. 4]

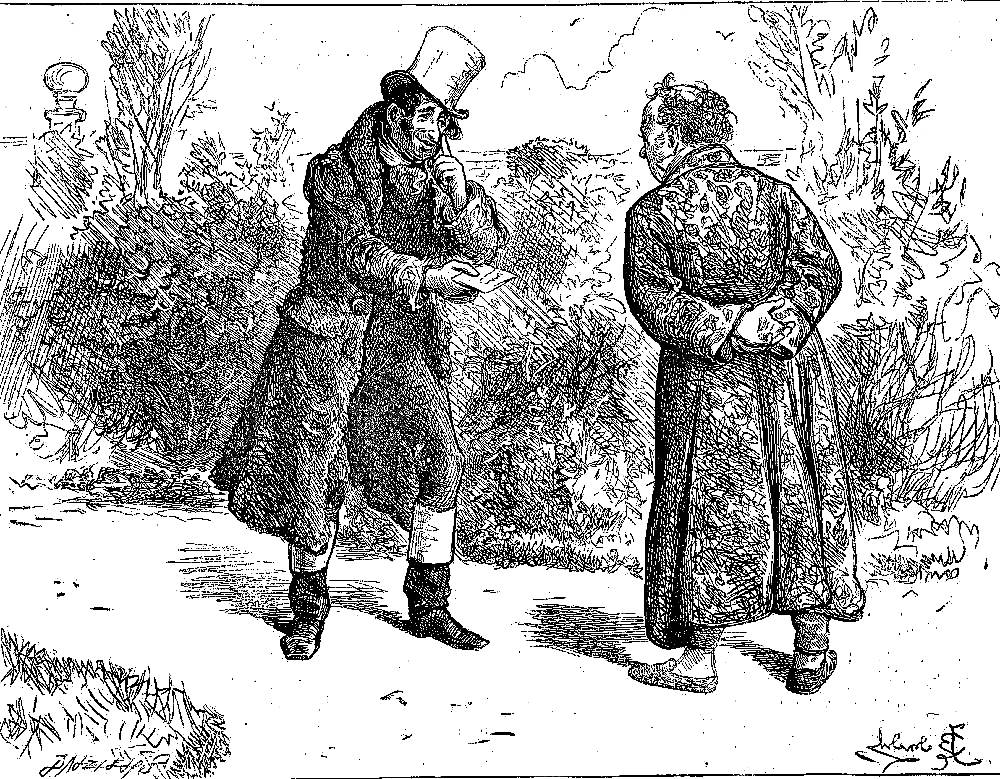

In the 1839 edition, "A Passage in the Life of Watkins Totle" was the only selection to be accompanied by three Cruikshank copper-plate engravings. No new illustrations for the story appeared when Chapman and Hall re-issued Sketches by Boz in the Library Edition (1858). The Ticknor Fields Diamond Edition, issued to coincide with Dickens's second American reading tour (1867), had only eight small-scale wood-engravings for Sketches by Boz — one of these, entitled Watkins Tottle, depicts Parsons and Tottle learning from the Rev. Timson that he has won Miss Lillerton's hand. However, when Chapman and Hall contracted Fred Barnard to illustrate the London sketches for the 1876 Household Edition, the slender, double-columned volume contained three large-scale wood-engraving for this storys; the following year, the Harper and Brothers Household Edition volume, contained twenty-eight wood-engravings for that part of the volume involving the Sketches, two of which Frost devoted to the story.

The later illustrators of the story, using the original Cruikshank trio of copper-plate engravings as their point of departure, have focussed on the interesting but minor figure of the sheriff-officer's mercury (messenger), who in the second chapter delivers the news to Parsons that Tottle has been apprehended for debt, and on Parson's flashback to his own rather rocky courtship of Fanny. This is the only story in the 1839 Chapman and Hall anthology to receive three illustrations, and one of the few in the 1876 Household Edition to receive more than a single wood-engraving, so that both elements, the farcical marriage plot and the ridiculous superannuated bachelor's failed attempt to secure a wealthy bride, must have been very appealing to George Cruikshank, Sol Eytinge, Junior, Fred Barnard, A. B. Frost, and Harry Furniss.

Illustrations from the 1839 and Other Editions for "Watkins Tottle"

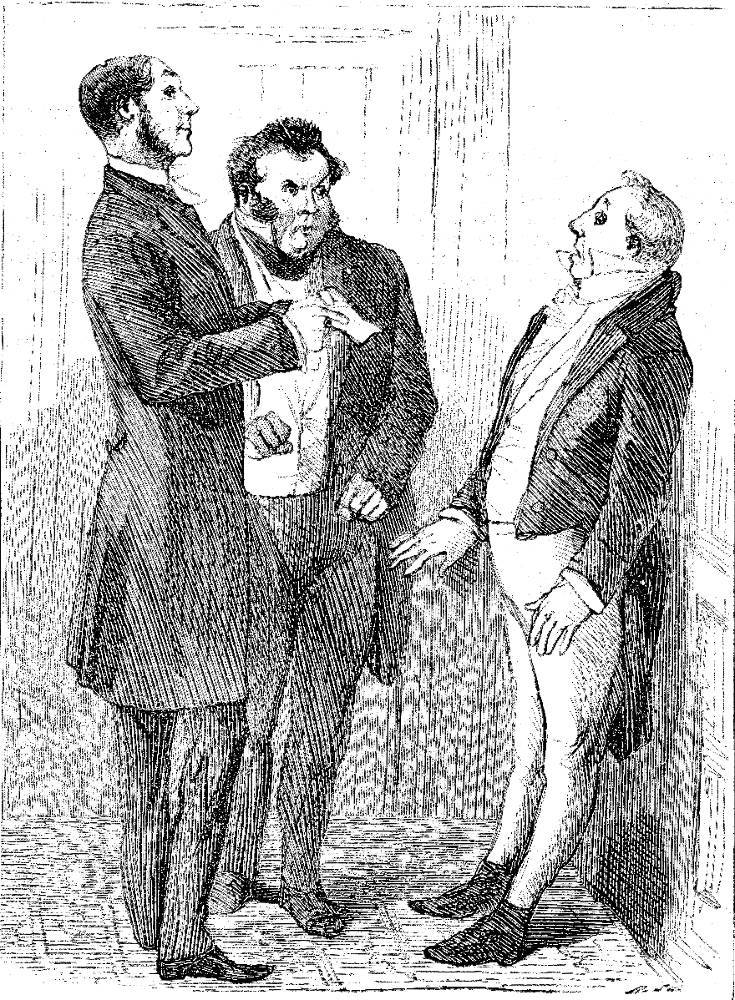

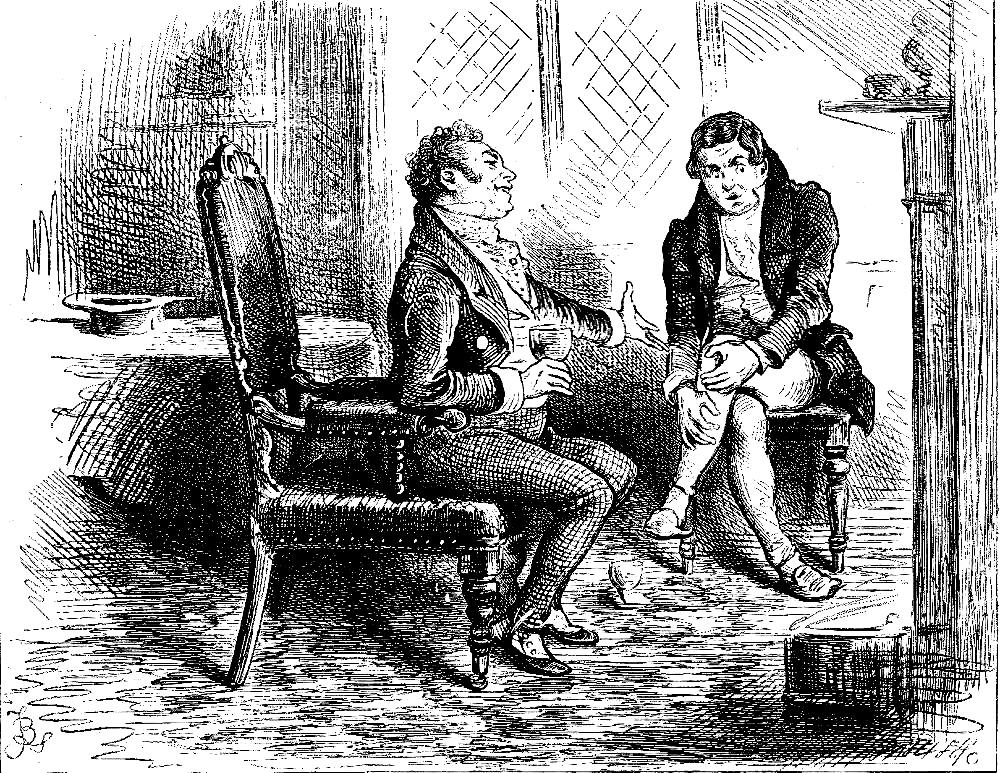

Left: Cruikshank's initial illustration for the story, introducing the timid protagonist, Watkins Tottle. Left of centre: Cruikshank's third illustration, which suggests that Tottle will be successful in his courtship of the affluent spinster, Mr. Watkins Tottle and Miss Lillerton. Right of centre: Eytinge's single illustration, featuring Tottle (right), Rev. Timson (lefty), and Parsons (centre), as they learn of Miss Lillerton's engagement to the Anglican minister, Mr. Watkins Tottle (1867). Right: Furniss's realisation of the agent of the lock-up house, The Sheriff-Officer's Mercury (1910).

The Relevant Illustrations from The British Household Edition (1876)

Above: Fred Barnard's wood-engraving of the interview between Parsons and Tottle in the two-part short story, "Why," replied Mr. Watkins Tottle, evasively; for he trembled violently, and felt a sudden tingling throughout his whole frame; "Why — I should certainly — at least, I think I should like —" — to marry the wealthy spinster, Miss Lillerton.

Above: Fred Barnard's wood-engraving of the scene in which Solomon Jacobs' minion reveals that Tottle has been apprehended for debt, "I've brought this here note," replied the individual in the painted tops in a hoarse whisper; "I've brought this here note from a gen'l'm'n as come to our house this mornin'."

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. ""A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 326-55.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor and Fields edition]. Pp. 465-85.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 115-117.

Dickens, Charles. Part IV, "Tales," Chapter X, "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by A. B. Frost. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877. Pp. 253-68.

Dickens, Charles. "A Passage in the Life of Mr. Watkins Tottle," Chapter 10 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 419-55.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 26 April 2019