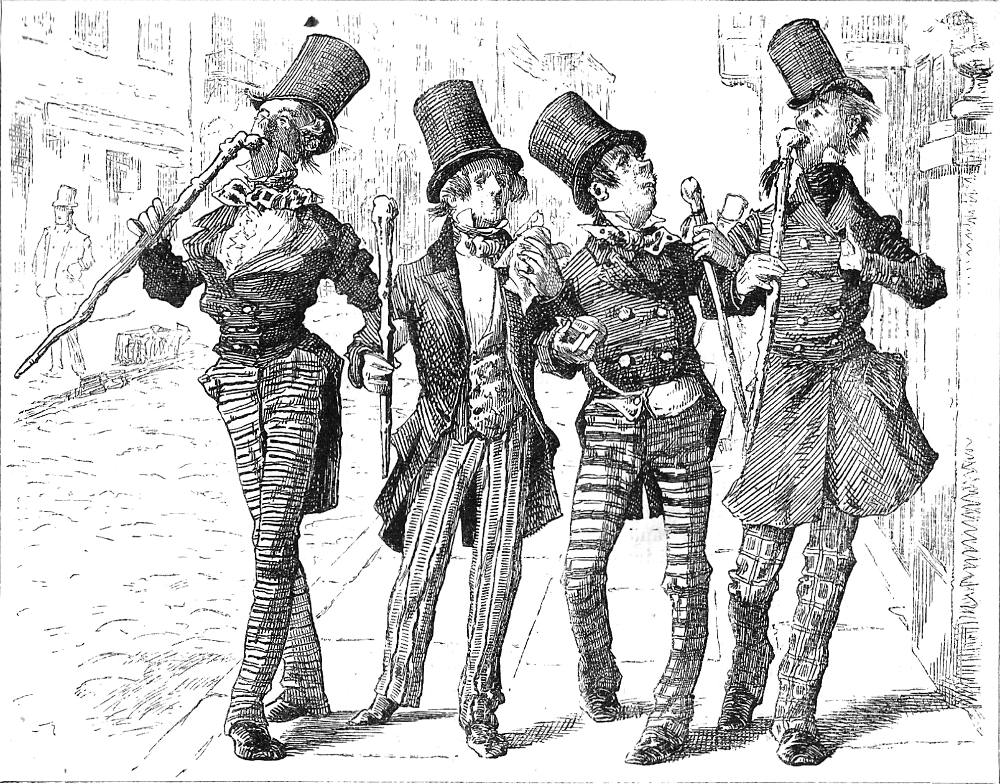

There were four of them, all arm-in-arm by A. B. Frost, in Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day People and Every-day Life, Pictures from Italy, and American Notes. (1877), "Characters," Chapter I. "Thoughts about People," page 171. Wood-engraving, 4 ⅛ by 5 ¼ inches (10.5 cm high by 13.5 cm wide), framed. As in "We are going to marry Mr. Robinson" in "The Four Sisters," Frost seems far more interested in the blurring of identities among London characters than his predecessors, who focussed on the plight of the solitary clerk in this sketch, emphasizing pathos over character comedy. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Information

Originally published as "Sketches of London, No. 10" in The Evening Chronicle for 23 April 1835, this sketch describes three metropolitan types: a poor clerk (illustrated by Cruikshank and Barnard), a wealthy, aged clubman, and a brace of young apprentices out for a stroll in their finery on a Sunday afternoon, described by Frost. The 1876 and 1877 Household Editions of Dickens's Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People contain two wood-engravings for this piece.

Passage Illustrated: Four Jolly Apprentices

But, next to our very particular friends, hackney-coachmen, cabmen and cads, whom we admire in proportion to the extent of their cool impudence and perfect self-possession, there is no class of people who amuse us more than London apprentices. They are no longer an organised body, bound down by solemn compact to terrify his Majesty’s subjects whenever it pleases them to take offence in their heads and staves in their hands. They are only bound, now, by indentures, and, as to their valour, it is easily restrained by the wholesome dread of the New Police, and a perspective view of a damp station-house, terminating in a police-office and a reprimand. They are still, however, a peculiar class, and not the less pleasant for being inoffensive. Can any one fail to have noticed them in the streets on Sunday? And were there ever such harmless efforts at the grand and magnificent as the young fellows display! We walked down the Strand, a Sunday or two ago, behind a little group; and they furnished food for our amusement the whole way. They had come out of some part of the city; it was between three and four o’clock in the afternoon; and they were on their way to the Park. There were four of them, all arm-in-arm, with white kid gloves like so many bridegrooms, light trousers of unprecedented patterns, and coats for which the English language has yet no name — a kind of cross between a great-coat and a surtout, with the collar of the one, the skirts of the other, and pockets peculiar to themselves.

Each of the gentlemen carried a thick stick, with a large tassel at the top, which he occasionally twirled gracefully round; and the whole four, by way of looking easy and unconcerned, were walking with a paralytic swagger irresistibly ludicrous. One of the party had a watch about the size and shape of a reasonable Ribstone pippin, jammed into his waistcoat-pocket, which he carefully compared with the clocks at St. Clement’s and the New Church, the illuminated clock at Exeter ‘Change, the clock of St. Martin’s Church, and the clock of the Horse Guards. When they at last arrived in St. James’s Park, the member of the party who had the best-made boots on, hired a second chair expressly for his feet, and flung himself on this two-pennyworth of sylvan luxury with an air which levelled all distinctions between Brookes’s and Snooks’s, Crockford’s and Bagnigge Wells. [III. "Characters," Chapter I. "Thoughts About People," p. 172]

Commentary: The Look-a-Likes out for a Stroll on a Sunday Afternoon

As Dickens's reference to William IV ("his Majesty’s subjects") suggests, this early sketch preceded Victoria's ascension. The sketch's original title in the Evening Chronicle was not particularly informative: "Sketches of London, No. 10." The sketch concerns three London types: the first, a poor, friendless clerk who, oyster-like, lives an insulated existence (not unlike that of Nicolai Gogol's clerk in "The Overcoat"); the second, an affluent collector of books; the third type, the one which Frost has chosen to realise, is the London apprentice. Four of these flashily dressed fellows in coloured waistcoats, frock-coats, and loud-patterned trousers take their Sunday afternoon off to strut about the streets and parks of the City. Here, they literally fill the width of the broad sidewalk beside a thoroughfare. Frost has made them both true to the types and individuals, with the apprentices to the left and right being taller than their fellows in the centre; each also wears a slightly different cut of jacket. To demonstrate, however, that they are not truly individuals, Frost has left one of the faces a mere mask.

A Legion of Apprentices

Whereas Dickens's other illustrators have focussed on the pathetic figure of the poor clerk, Frost has depicted four look-alike apprentices out for a Sunday afternoon stroll. As Dickens makes clear in Oliver Twist, the apprenticeship system depended upon the parish workhouses to supply the children who would serve apprenticeships for various trades into their adolescence. Under the Statute of Artificers (1563), an apprentice would serve a fixed term of indenture of seven years; the apprenticeship would always conclude by the time that the youth reached 24 years of age, although this figure was reduced to age 21 in the eighteenth century. The workhouses were continually receiving large complements of children in the age range of 13-16, but the proportion of males to females increased after the Napoleonic Wars, making it more difficult to find apprenticeships for the boys. One of the country's largest poorhouses, that in the parish of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, Westminster, which had a population of about 30,000 in the first half of the nineteenth century, sought to apprentice girls from about the age of seven and boys from about the age of ten. However, as the parish was constantly having to accept older children, it sought to farm them out as soon as possible. Thus, the boys let out to become apprentices would often have known one another in he workhouse, and would have a unique bond, making them (as Frost shows) de facto brothers. Dickens's readers would subsequently have become familiar with London apprentices through figures such as Sim Tappertit, Varden's conceited apprentice and leader of the 'Prentice Knights, in Barnaby Rudge (1841) in Master Humphrey's Clock.

The commercial engine of trade and labour in Greater London seems to have depended upon the workhouses to supply its needs: for example, according to the fairly accurate records of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, "between 1725 and 1824 it apprenticed over 3,000 children from the workhouse" (Schwarz and Boulton), although not all of these would have become full-fledged apprentices since the employer could (and often did) reject the candidates whom the workhouse sent him.

The expectations on apprentices and their masters or employers were legally binding and were laid out in an indenture that stipulated the reciprocal duties owed. Apprentices would work for a defined period of time during which they would live in the house of their employer or master and receive board and lodgings. In return they would receive training in a particular craft. As well as their labour apprentices were liable to a fee, known as a premium, which would be paid to the master or employer, usually on behalf of the apprentice by his or her parents or by a charitable institution. The length of an apprenticeship and the requirement to ‘live in’ meant that the training offered went beyond transferring the skills of a particular trade or craft to a young worker. They covered a broader range of knowledge and behaviours including literacy, morality, domestic skills and religious instruction, hence the relationship between a ‘live-in’ or ‘indoor’ apprenticeship and his or her master went beyond an economic one. [Cowman]

Related Material

- Afternoons in the Park

- Cruikshank's "Thoughts about People — The Poor Clerk

- Barnard's His spare pale face looking as if it were incapable of bearing the expression of curiosity or interest

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cowman, Krista. Apprenticeships in Britain c. 1890–1920 An overview based on contemporary evidence." Pp. 1-12. University of Lincoln. Web. November 2014. Accessed 11 April 2019.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 159-62.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 345-47.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 101-03.

Dickens, Charles. Section 3, "Characters." Ch. I, "Thoughts about People." Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day People and Every-day Life, Pictures from Italy, and American Notes. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and Arthur B. Frost. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1877 (copyrighted in 1876). Pp. 170-72.

Dickens, Charles. "Characters," Chapter 21, "Thoughts about People," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 204-08.

Schwarz, Leonard, and Jeremy Boulton. "Parish apprenticeship in eighteenth century and early nineteenth-century London." University of Birmingham and University of Newcastle. Pp. 1-7. Web. 11 April 2019.

Last modified 11 April 2019